Although neurodiversity as a term may have been around for the last 30 years or so, it is still not widely understood to refer to people with a range of neurological conditions from autism and dyslexia to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD.

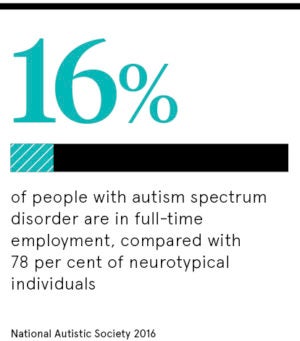

Another issue is that because neurodiverse individuals have a different way of thinking about the world, they are often misunderstood, which tends to mean employment rates are low. Research by the UK’s National Autistic Society indicates that while around 700,000 people, or 1 per cent of the population, have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), only 16 per cent are in full-time employment compared with 78 per cent of neurotypical individuals.

The US-based Center for Disease Control and Prevention, meanwhile, estimates that more like one in 59 people are on the spectrum, with the condition being four times more common in boys. But as few as 14 per cent currently hold jobs, according to the National Autism Indicators Report by Philadelphia’s A.J. Drexel Autism Institute.

It’s always people who have thought differently that have made the major breakthroughs

Why aren’t more employers embracing neurodiversity?

Mike Spain, founder of the UK’s Cyber Neurodiversity Group, which co-ordinates inclusion activity across the cyber industry, attributes this situation to a “degree of fear” about neurodiversity among many employers.

“There’s an element of ‘what would we be letting ourselves in for?’” he says, “but an even bigger fear of getting it wrong and possibly making things worse.”

A key problem here is that ASD, along with other neurodiverse conditions, has traditionally been portrayed as a disability rather than simply a different way of thinking about things.

However, there are two sides to every coin, says Matt Trerise, training and liaison worker at NHS Bristol Autism Spectrum Service, who is also providing training for the UK’s Direct Marketing Association’s Neurodiversity Initiative to help employers become more autism friendly.

“You could say that many people with autism struggle to work out what others are thinking and feeling as they find it difficult to read non-verbal cues, and this means they have insulated minds that aren’t affected by others,” he says. “But if you flip that, you could say it means there’s a possibility of genuinely original thought and it’s always people who have thought differently that have made the major breakthroughs.”

It is important not to pigeonhole neurodiverse individuals

Mr Trerise indicates that it is important not to stereotype individuals with ASD by pigeonholing them into certain kinds of jobs and industries as their talents and abilities are as diverse as those of neurotypical individuals. But he acknowledges that many people on the spectrum are logical and analytical thinkers, show strong attention to detail and are good at spotting patterns. They also tend to be loyal, reliable and honest.

As a result, areas such as computer science, engineering, maths and the sciences in general are often a draw. Jobs in data science and analysis, as well as software development and testing, frequently appeal in sectors ranging from professional services and finance to IT and marketing.

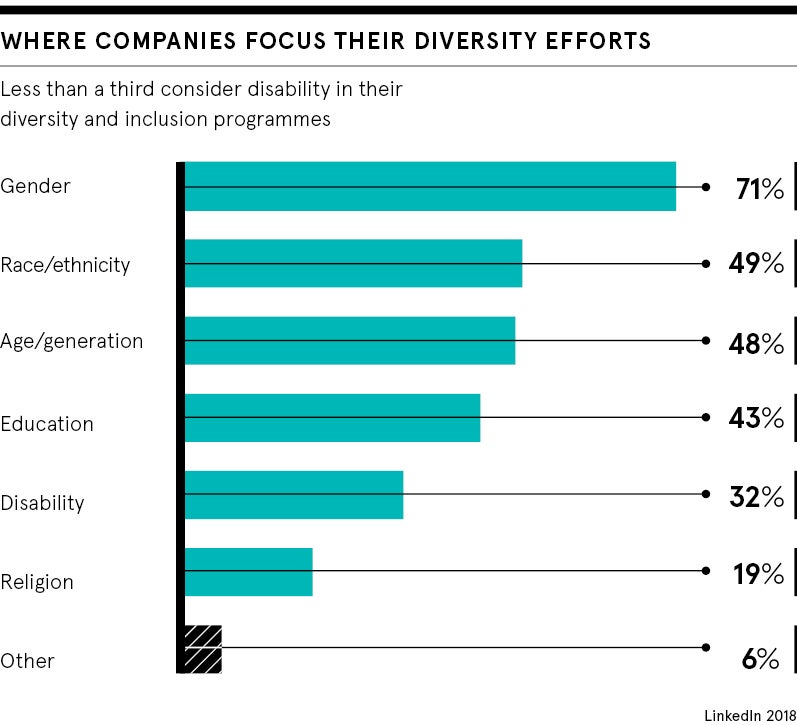

But there are real commercial benefits to be gained from neurodiversity, which means activity needs to move beyond today’s predominant realm of diversity and inclusion or corporate social responsibility initiatives, says Ray Coyle, chief executive of IT consultancy Auticon, which specialises in employing autistic adults. It should be about more than simply filling skills gaps, he says.

“Instead it’s about improving business performance, especially as we become an increasingly technology and data-led society,” says Mr Coyle. “So having people with different problem-solving abilities, who are able to think in a different way, will become more and more important for organisational success.”

How to create a culture inclusive of neurodiversity

To obtain these benefits though, it is vital to have the right kind of inclusive company culture in place. Mr Spain explains: “It’s about creating an environment in which people can excel. So it’s not a case of singling out individuals with autism; it’s about moving to an inclusive culture, where any changes you make will support and benefit everyone.”

To achieve this, he says, requires three key elements: the right roles, the right environment and the right leadership. In leadership terms, for example, it is imperative that senior executives are on board to champion any cultural change and lead by example.

Investment in time and resources will be required on the part of line managers and their teams in the form of training. The aim is to help them understand the needs of neurodiverse people, how to communicate effectively with them and how to make the workplace adjustments required to ensure they feel comfortable.

For example, in communication terms, it is vital to speak in clear, plain English as people with ASD find it difficult to understand metaphors, irony and sarcasm.

As Mr Coyle explains: “Workplace communications and structures are built around neurotypical people, so there’s lots of ambiguity and unwritten rules that people with ASD don’t understand. This means it’s important to bring in a more logical approach and clarify reporting lines, so people don’t end up getting contradictory requests that they have to prioritise.”

Having people with different problem-solving abilities, who are able to think in a different way, will become more and more important for organisational success

Many adjustments for neurodiverse workers could benefit all

The same theory applies to job adverts, which are usually written from the hypothetical point of view of an ideal individual. “But this doesn’t work for people on the spectrum as they take the requirements literally and at face value,” Mr Coyle says. “So job adverts need to be more concrete and specific in terms of the skills being looked for.”

Undertaking skills testing rather than focusing on a traditional interview process can make a big difference when it comes to neurodiversity. But once neurodiverse candidates have been recruited, another key consideration is ensuring the physical environment is appropriate to their needs.

For instance, some individuals with ASD are photo or sound sensitive and may benefit from sitting away from windows or working with headphones on. Many also find hot desking difficult due to its unpredictable nature and, therefore, value having a dedicated space of their own or working from home.

But as Mr Trerise points out, going down this route is generally beneficial for neurotypical people too. “Adjustments, such as cutting through jargon and adding more structure to meetings, aren’t complex or expensive, but they can help to create a better working environment for all,” he says. “It’s about playing to people’s strengths and supporting them to be the best version of themselves they can be, and that kind of approach benefits everyone.”

Why aren't more employers embracing neurodiversity?