Automation has the potential to boost productivity in the UK and increase GDP by 10 per cent by 2030, adding another £232 billion to the economy, PwC predicts. But such gains will be undermined by severe job losses. Some 44 per cent of jobs in the UK are forecast to disappear, affecting £290 billion of earnings and accounting for a third of all annual pay, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).

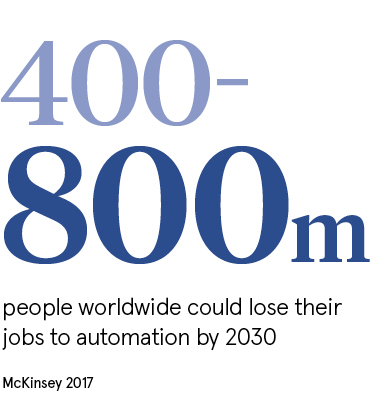

While the emergence of new jobs and new categories of work is likely, it is certain that swathes of society, potentially whole generations in some industries, will face periods of unemployment. Globally, McKinsey estimates that between 400 million and 800 million people will be forced to find new jobs, with as many as 375 million of them switching to entirely new occupational categories.

At the same time as automation looms large, the jobs market is becoming more insecure. Almost all (94 per cent) of the ten million US jobs created between 2005 and 2015 were for independent contractors, freelancers, temporary agency workers and the gig economy, according to research by economists Lawrence Katz of Harvard University and Alan Krueger of Princeton University. During that period, the proportion of American workers engaged in temporary or insecure work grew from 10.7 to 15.8 per cent.

At the same time as automation looms large, the jobs market is becoming more insecure. Almost all (94 per cent) of the ten million US jobs created between 2005 and 2015 were for independent contractors, freelancers, temporary agency workers and the gig economy, according to research by economists Lawrence Katz of Harvard University and Alan Krueger of Princeton University. During that period, the proportion of American workers engaged in temporary or insecure work grew from 10.7 to 15.8 per cent.

In the UK, the Trades Union Congress estimates that more than three million people work in insecure jobs, up from 2.4 million in 2011, representing one in ten workers.

Against a backdrop of rising inequality, ten years of real wage stagnation and growing rates of working poverty, many believe the UK is ill-prepared for the social dislocation the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution will wreck.

There is growing recognition that people will require a stronger, wider and simpler safety net. According to a GMB poll of 1,000 precarious workers, 78 per cent had previously been in permanent employment, 69 per cent said their cost of living is rising faster than their earnings and 61 per cent report suffering stress or anxiety as a result of their current work.

By giving people the security and space to plan and make their own decisions, we benefit as a society and can rebuild a sense of community

Universal basic income (UBI) is a proposal to help workers weather future job-market insecurity. Originating in the Renaissance philosopher Thomas More’s 1512 work Utopia, it is a radical reinterpretation of the social contract between citizen and state. Every citizen, regardless of whether they are in work or not and no matter how much they earn, would receive a monthly stipend from the state providing the minimum amount necessary to survive.

“The common headline is about free money, but at the end of the day it is about investing in the future and it uses money that we all contribute towards,” says Jamie Cooke, head of RSA Scotland. “By giving people the security and space to plan and make their own decisions, we benefit as a society and can rebuild a sense of community.”

Advocates propose that UBI would give workers more bargaining power with employers, and result in the creation of better quality and higher-paid work. This in turn would create a virtuous cycle of higher work participation and effort to improve skills.

Mr Cooke also points to wider benefits to the welfare state. “UBI will cost more in the short term, but the longer-term impacts, such as increased personal responsibility and potential reduction of pressures on the health service, could save money,” he says.

The idea is also rooted in fairness. Given the financial returns from automation will asymmetrically benefit shareholders over workers, UBI would offer a means of redistributing this new-found wealth.

What remains to be seen is how UBI would look in practice. Trials are underway in Scotland, Finland, Canada, United States and the Netherlands to test a range of hypotheses, but the biggest question on everyone’s lips is how much would people get? Peg it too high and it is feared UBI could lead to mass labour market withdrawal; too low and it could end up exacerbating poor pay and working conditions if other workers are willing to reduce their wages for lack of alternatives.

The most advanced of the trials underway, in Finland, has a clear purpose to see whether an unconditional income given to unemployed people would help them back into paid work. Established by Finland’s right-wing government the project gives participants the same amount of money they would receive under unemployment benefits, but with no strings attached. No demands, no sanctions and no bureaucracy. The Finns hope UBI will remove some of the disincentives that put people on benefit off seeking work, such as the higher marginal rate of tax on income.

Just as UBI has supporters on the political left and right – the neoliberal economist Milton Friedman laid out a closely related proposal with his “negative income tax” – it also has critics on both sides of the political divide. Most point to unforeseen costs and distortions to the economy. Will UBI lead to fewer people accepting low-paid jobs, and a consequent rise in the price of basic goods and services? Would it cause inflation?

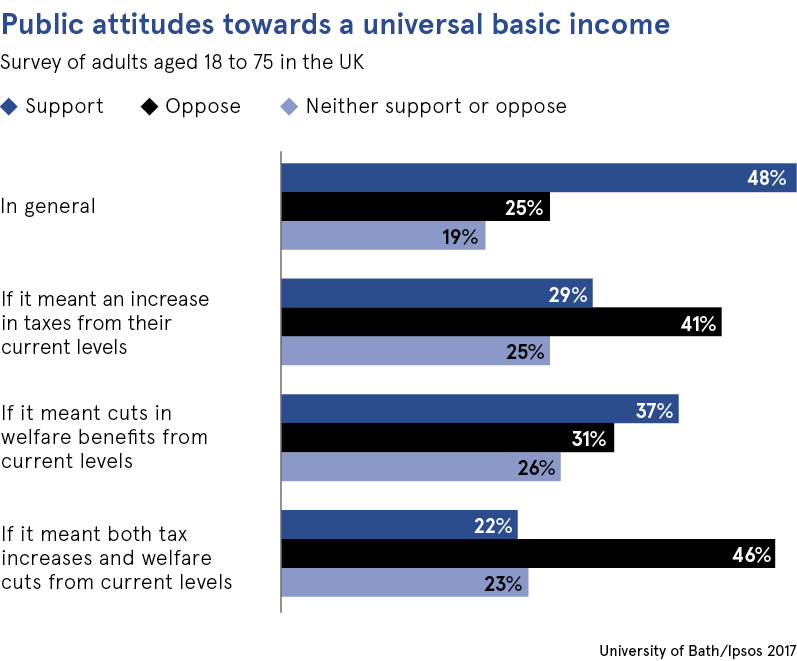

Among the general public, UBI is popular in theory. A University of Bath survey found 48 per cent of 18 to 75 year olds support it, but that percentage dropped significantly to 30 per cent when respondents were asked to consider the fiscal impacts, such as tax rises and cuts elsewhere.

Which leads to the most fundamental question of how would we pay for it? Most proponents believe UBI would necessitate tax reform. The most obvious being the removal of the personal allowance, resulting in taxation of all income earned. There is also some consensus that it would be illogical to fund UBI solely through tax hikes on top earners. Suggestions include a carbon levy which would also help curb pollution, a land value tax, financial transaction tax and allocation to the state of a percentage of shares from every stock market launch.