As the coronavirus pandemic has unfolded, the nature of employment has changed rapidly. Lockdown procedures mean employees are working from home, with workers in many sectors finding, for the most part, it’s entirely possible to work away from the office. Tools like Zoom, Slack and Teams enable staff to communicate and collaborate effectively at a distance, leaving many questioning the need for offices at all.

On the flipside, however, is that every aspect of the people management process now happens over Zoom, including being made redundant.

Hit by COVID-19, many companies have found themselves flailing financially and hundreds of thousands of jobs have already been lost, with many more employees furloughed. Employers have been left needing to cut positions and video calling may seem like the most personal option of breaking the news.

But bad internet connections, poor communication and a lack of eye contact are just a few things that have left employees in the firing line feeling as if they don’t have any closure.

It doesn’t look like we’ll all be back in offices anytime soon, which means employers may need to continue letting people go over video chat. But how does being made redundant remotely affect employees? How can employers and human resources leaders manage feelings with empathy while still making the decisions they need to?

Employers need to consider employees’ feelings

Making someone redundant over Zoom doesn’t excuse employers from the difficult job of having to manage the complex emotions involved. In fact, it may mean they need to make more of an effort. Deborah, 54, was working for a Silicon Valley tech company after being headhunted by the chief executive. When COVID-19 hit, she had no fear of losing her job until her company called a last-minute emergency meeting. With no warning, she accidentally missed the Zoom meeting, watched the recording and then had to wait three hours to be told she was being laid off.

“When we finally spoke, my boss, whom I considered a friend, was obviously so upset. I felt in that moment like I had to manage her feelings,” says Deborah. “If a CEO has to do these layoffs, I think they should offer a chance for the employee to sit and think about what has just happened. If the employee responds with, ‘are you OK?’, they should say, ‘I’m not the one losing my job; you don’t have to manage my feelings’.” She found the lack of eye contact in particular difficult: “There’s a true connection that’s forged by eye contact.”

A shared experience by people who have been made redundant over Zoom is they all felt they weren’t given enough time, either as a warning or to process. Dan, 39, was working in medical research when he was let go. “It was a Zoom call, with no topic in the meeting other than, ‘to discuss the end of your furlough’,” he says. “I was on video, neither HR nor manager were. It was all very civil and lasted about ten minutes.”

That lack of communication, perhaps a result of the employer’s awkwardness, is common. Charlotte, 29, was working as a sales developer. “I had no idea. I was asked to attend a meeting with an hour’s notice, alongside my colleague who did the same job. I had no idea this was coming,” she says.

Danielle, 25, who was working in public relations, did not realise there would be redundancies. “We all received a Slack message on the main channel that there would be an important team meeting after lunch. At that moment I had a gut feeling that it had to do with job cuts and it turned out it was a Zoom meeting with everyone in the company for the chief executive to say that we’ve all been made redundant.”

I was asked to attend a meeting with an hour’s notice, alongside my colleague who did the same job. I had no idea this was coming

Jessica, 36, was also not warned. Since the start of the pandemic she had been working remotely to take care of her partner and was told on a Friday in a Zoom meeting with her chief executive, boss and the co-founder. “The meeting started without me having a clear idea of what the meeting was. They did not explain what the situation was and I was asked to speak first. I was in tears by the end of the meeting and a little in shock,” she says, adding she just wishes they had been clear about what the meeting was about.

How can employers learn from these mistakes?

These stories paint a bleak, inhumane picture of being fired or made redundant in the grip of COVID-19. However, crucially, they can offer important lessons for employers looking to inject empathy into a necessary process. First of all, employees need fair warning, an understanding of what a meeting will be about, so they can go into it emotionally prepared. “I feel that employers need to be transparent and open with their staff and give them as much information as possible if they have to terminate someone,” says Charlotte.

Danielle agrees that transparency is key. “It would have been better if we were given prior notice of the possibility of being made redundant or individual meetings could have been arranged to give us a heads-up due to a decrease in cash flow,” she says. “They should be open and honest at all times about the rate to which the company is losing its clients. I understand no employer wants to see their company crumble and it can be painful to have to explain this to employees, however the COVID-19 situation is not the employer’s fault.”

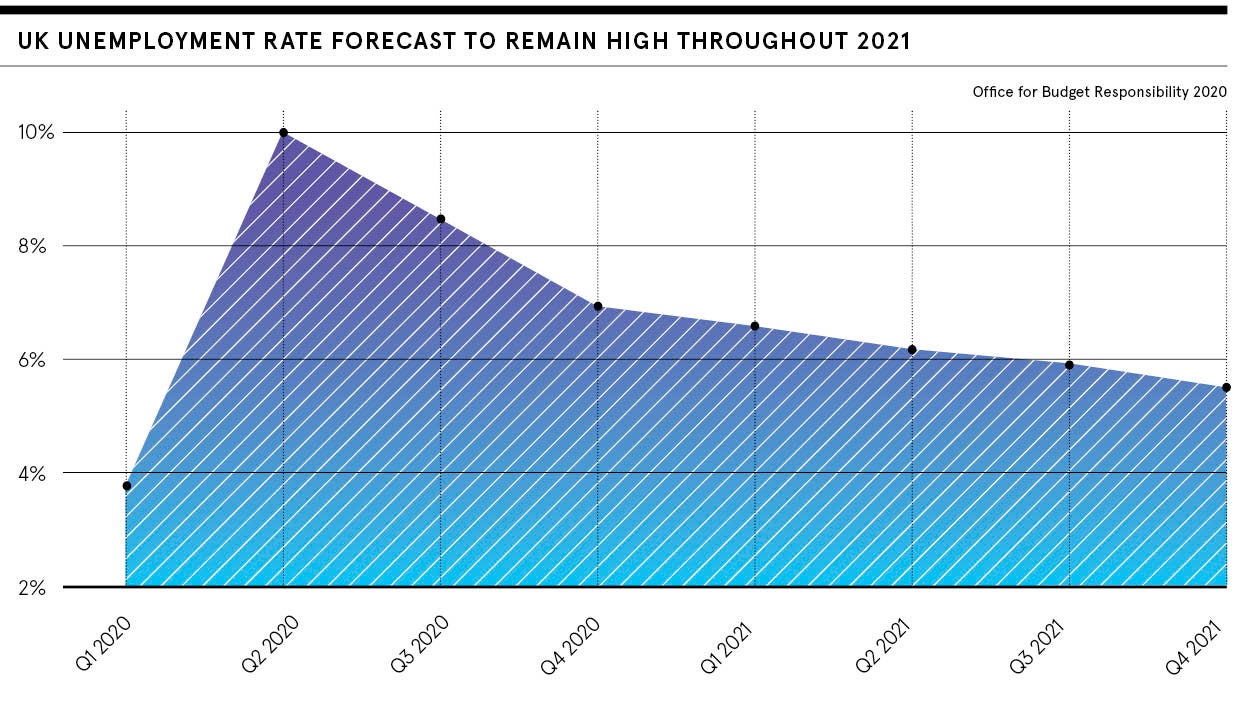

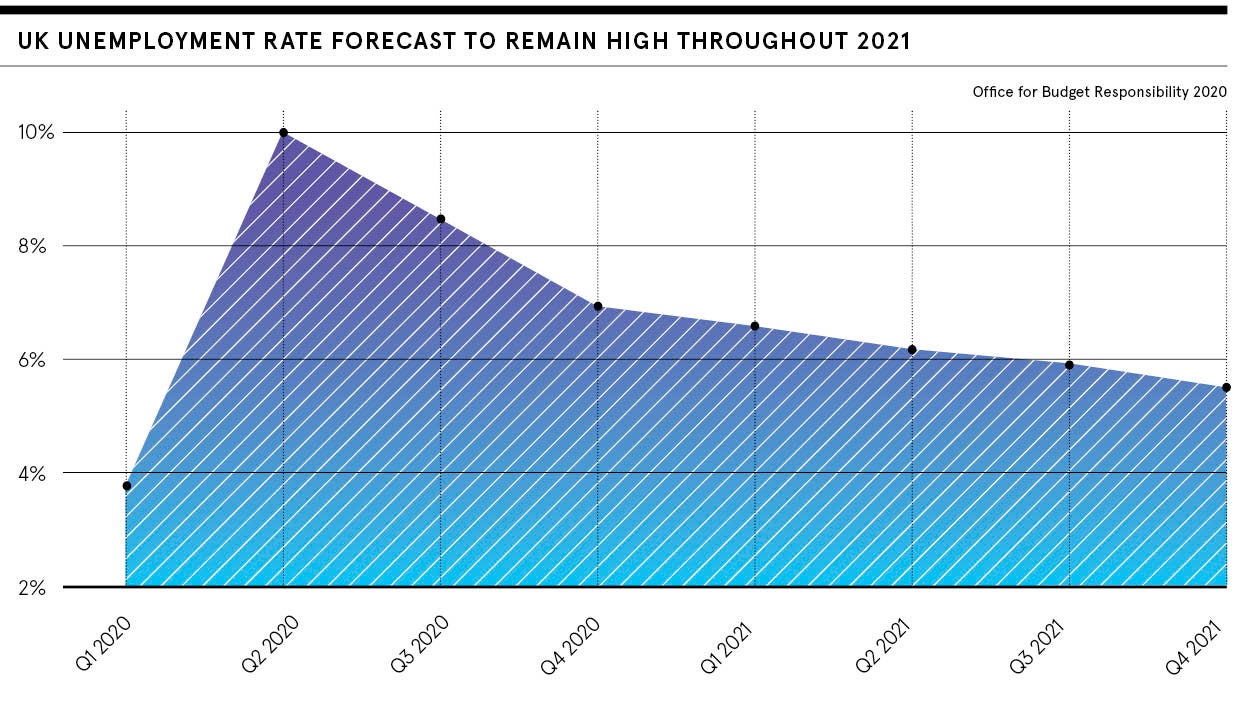

We are all, employer and employee alike, adapting to a new world. There will be complications and growing pains, but what’s important is that we remain adaptable and do everything, whether it’s hiring, working or firing, with humanity and in keeping with employment law, especially as employees are sent out into an unstable job market and economy. Redundancies are inevitable, but letting people go with empathy is a choice, even over Zoom.

Employers need to consider employees’ feelings