Does Patty McCord, former chief talent officer at Netflix, have a point? In her just-published article on corporate pay for Harvard Business Review, she doesn’t mince her words. “The prevailing system is behind the times,” she slams. “It’s based on what employees have produced, rather than their potential to add value in the future. Far better to focus on the performance you want and the future you’re heading to.”

In a year already dominated by demands for pay equality, notably between men and women, Ms McCord is the latest in an emerging group of commentators who believe a new discussion is needed about differing pay. Once this might have been called meritocracy; today though it’s all about what Ms McCord calls the “value-add of individuals”.

She says: “Rather than pay top rate for every position, identify those with the greatest potential to boost performance and pay top dollar filling them.” At Netflix she confessed she had no problem paying twice the rate as an existing similar-level person if they moved the company on twice as fast. She did what human resources directors (HRDs) are now expected to do all the time and identify where the most value comes from.

Until pay is thought about in terms of business outcomes, the conversation won’t change – but it should

So she’s right isn’t she, that if this is the case, the logical extension of this is to reincorporate inequality? In other words, pay should follow those who give the most return.

“While there’s no excuse for paying less based on gender or ethnicity, pay variation based purely on outcome really ought to extend to beyond just sales,” argues Mark O’Donoghue, CEO of learning firm AVADO, which equips staff, including employees at Google, to boost their skillsets. “Until pay is thought about in terms of business outcomes, the conversation won’t change – but it should.”

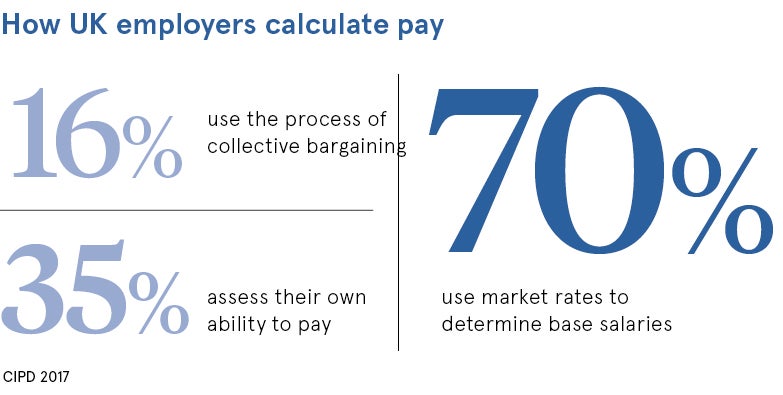

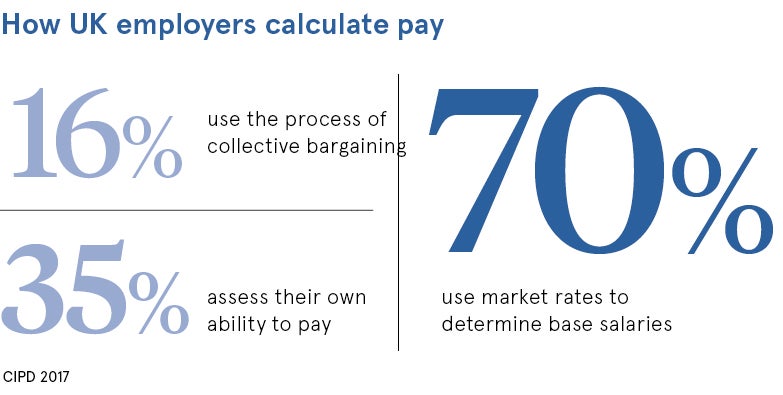

There’s one good reason most pay calculations still omit output. “When deciding pay, firms traditionally decide how large a role is, then they look at market rates and performance comes last,” says Dr Duncan Brown, head of HR consultancy the Institute for Employment Studies. “Why? Because of one key question: how do they measure the £-value that someone contributes?”

It’s no easy barrier to overcome. David Clift, HRD at TotalJobs, says: “It’s no surprise the harder a job is to ascribe a definite value to, the harder it is to reward on that basis and therefore it doesn’t have this element. The process hasn’t been made easier because work is increasingly more collaborative and team based.”

Nicola Britovsek, director of HR at Sodexo Engage, adds: “Our view is everyone has something to add and it can’t always be tangibly measured. Also, pay isn’t the only creator of value. I believe culture – how people feel at work – has just as important a role too.”

However, some believe that just because value is difficult to measure, it doesn’t mean companies shouldn’t try. James Reed, chairman of eponymous reed.co.uk, says: “I totally support the concept of giving staff some sort of indication of their value. Staff then see what they add or not. Letting it haunt them – in a good way – incentivises people to control their own development to add more value and therefore take-home pay.”

But while the sales profession is still where “value” is most clearly demonstrated, even in more prosaic sectors there are companies emerging that are giving pay by results a try. At public relations firm Stone Junction, founder Richard Stone allows people to trigger their own pay rises without management approval for hitting achievement measured against SMART objectives.

He says: “Equality and pay based on value created are not contradictory concepts; they are complementary. Equality is where talented people are paid differently according to their successes. Equal pay, irrespective of achievement, might sound utopian, but it’s most prone to manipulation. If you can’t be certain your boss is your boss because of their own success, then you can’t be certain that person hasn’t been unfairly promoted to a position of power.”

Some voice concern that doing similar assessments might unwittingly threaten other value-creating behaviour. Mr Clift goes so far as arguing large differences in pay, even those with clear results based justification, can actually stifle team creativity. “It’s a fact – staff talk about pay,” he says.

Demonstrating value

A linked debate is whether HRDs should come up with value metrics or whether staff should devise their own. Paul MacKenzie-Cummins, managing director at reputation management agency ClearlyPR thinks the latter. “It’s down to individuals to demonstrate the value they can add to the organisation and ‘sell’ themselves against that value,” he says. “Yet too few people do this well enough and it starts early in their careers.”

But, while some may not agree with this, what there does seem to be consensus on is the need make any reasons for differentials very clear.

“Where staff are paid according to value, they must understand how differentials arise,” says Emma Bartlett, partner at law firm Charles Russell Speechlys. “As value-added becomes harder to measure, transparency becomes even more important to mitigate inferences of unconscious bias.”

Lisa Forrest, global head of talent acquisition at Alexander Mann, says: “As long as organisations define what value looks like, colleagues who outperform others should be rewarded. Those who simply meet a target should not be offered an identical rewards package.”

Stephen Frost, author of Inclusive Talent Management, opts for a wide range of measures. “Monetary value created is important, yes,” he says. “But HRDs should also include things like feedback from customers, teams and the engagement scores they create, as these impact organisational value too.”

Clearly it’s tough defining someone’s value. But make no mistake, it’s a trajectory that Ms Forrest only sees going in one direction. As more firms scale back their permanent headcount, with the rest outsourced to gig workers, she says: “Focusing on outputs has never been more significant. In the next five years we’ll see even more individuals opting for portfolio careers, which will further impact how value is measured.”