Last year, Jeremy Corbyn caused bewilderment by suggesting the UK should be investing in cyber physical systems. Observers on Twitter wondered whether he was talking about The Terminator, while The Guardian explained he was referring to “driverless cars and stuff”.

In fact, the Labour leader was referencing one of the key elements of the factory of the future: production systems that can autonomously exchange information and control one another through the integration of computation, networking and physical processes.

The concept has a lot in common with the internet of things (IoT), but takes it one step further. While IoT devices are interconnected, it’s only with cyber physical systems or CPS that complex modelling, known as digital twinning, and analytic capabilities enter the stage, using sophisticated modelling to infer knowledge from the raw data, take decisions and send commands.

“The idea is you have the physical manufacturing plant and the simulated model of the plant, so if there’s a difference between the two, you can detect a fault or a cyber intrusion,” says Dawn Tilbury, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan College of Engineering. “The goal is to develop control systems for manufacturing systems that are secure and reconfigurable automatically.”

Clearly, CPS can have an enormous effect on productivity, reducing downtime and allowing a faster response to system disruptions such as faults or cyber intrusions, which can stop a production line dead and cost thousands of pounds every minute.

And it’s crucial for the factory of the future, which is a long way from the traditional assembly line.

“The factory as we know it today will change radically. Assembly lines will be replaced by flexible manufacturing islands and work pieces will communicate even more extensively with production machinery,” says Daniel Küpper, head of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Innovation Center for Operations.

“The growing complexity is the central challenge of production. The factory of the future will have to handle a much larger number of product variations, while at the same time increasing productivity.”

Audi’s R8 manufacturing facility in Heilbronn, Germany, for example, handles the large number of potential product options by doing away with fixed conveyors. Instead, driverless transport systems, guided by a laser scanner and radio-frequency identification or RFID technology embedded in the floor, move the car bodies on individual journeys through the assembly process, allowing changes to the assembly layout to be made quickly.

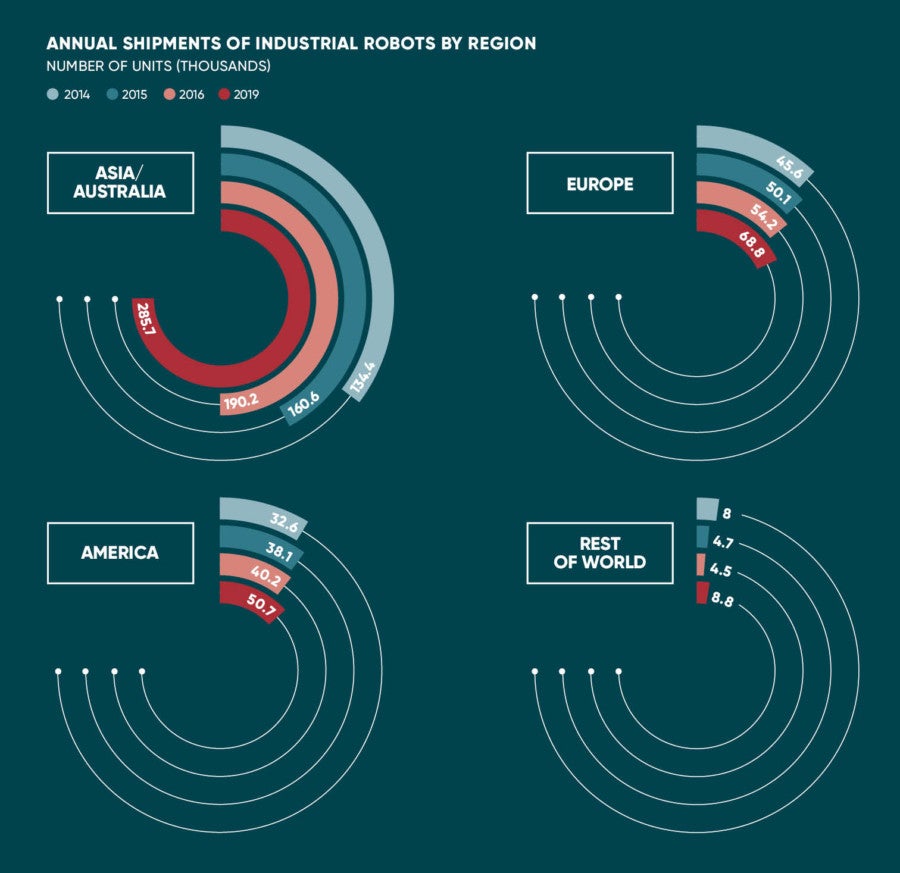

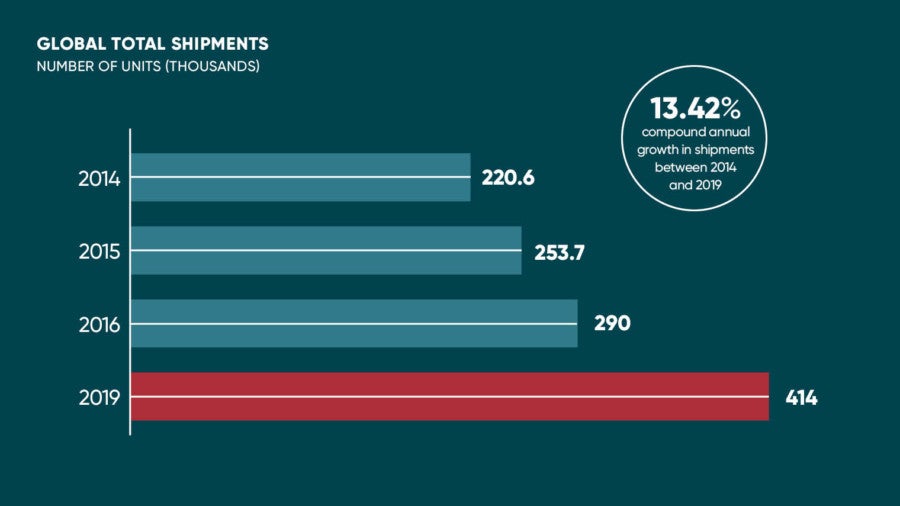

Of course, making the most of these capabilities involves the use of evermore sophisticated hardware, particularly robotics. In a report late last year, BCG found that 85 per cent of respondents from the automotive industry worldwide expect smart robots to be highly relevant in 2030.

Already, at Volkswagen’s plant in Wolfsburg, Germany, a collaborating robot tightens screws that are hard for workers to reach. Meanwhile, Chinese-US joint venture Changan Ford uses flexible industrial robots to process six vehicle models on a single welding line, switching from one to another within 18 seconds.

Augmented reality applications are also starting to appear with, for example, smart glasses guiding staff through work processes and notifying them of assembly errors or safety hazards.

The term Industry 4.0 was coined and promoted by the German government and it’s no surprise that German firms are at the forefront of the new manufacturing. According to BCG, 47 per cent of manufacturers in the country say they have at least developed their first concepts and many have gone further with highly encouraging results.

Assembly lines will be replaced by flexible manufacturing islands and work pieces will communicate even more extensively with production machinery

Siemens, for example, claims that by digitalising their value chains, its automotive customers have been able to cut development times by as much as 40 per cent and increase manufacturing volumes substantially with no loss of quality.

The UK, though, is a little slower in getting on board and Nigel Stacey, director at BCG, believes the UK government should take a leaf out of Germany’s book.

“The UK needs a broad and more coherent strategy to apply Industry 4.0, which our analysis suggests will make industrial production 30 per cent faster and 25 per cent more efficient,” he says.

“The UK government must continue to work with industry to bring stakeholders from business and academia together in a national co-ordinating body. The body should be capable of setting this strategy, developing awareness and understanding, and drawing up recommendations for action, as well as be backed by effectively targeted investment.”

Not as exciting as The Terminator, but a lot more constructive.