“Incestuous networks need to be dismantled. Black books need to be opened up. We need to start recognising that those who look, feel and sound different to us are probably the greatest gift the fashion industry could ever receive.” For an industry that has traditionally relied on recruiting through cliques and unpaid internships, fashion has a saviour in Farrah Storr, the editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan, whose impassioned words reflect a mission to open up opportunities in the industry.

Last month, the women’s glossy magazine launched a competition in partnership with flatshare site SpareRoom to offer four people a month-long paid scholarship with accommodation in central London included.

“One of the biggest criticisms of the media, and by association the fashion media, is that it is populated by those from a certain socio-economic background,” says Ms Storr. “You generally need to be in the capital to take up unpaid internships. That means you either need to be based in or around London, or have sufficient means by which to support yourself. So right there you are excluding large swathes of talent because of the class and postcode into which they were born.”

Unpaid internships have long been a staple for the arts

The reaction from a former fashion publishing intern, who spent several months at Vogue on an unpaid internship, was happy disbelief. “They get free accommodation? And the London living wage?” she asks. “I had to sleep on friends’ sofas and get help from my parents. Once Vogue was on my CV, I started to get loads of requests from other magazines to do unpaid internships. I thought a job would be just around the corner, but after 18 months my parents said enough was enough. I remember my dad saying that the industry was funded by the parents of intelligent young women.”

A recent study from The Sutton Trust, which aims to enhance social mobility through educational opportunity, found that 86 per cent of internships in the arts – TV, theatre, film, fashion – were unpaid.

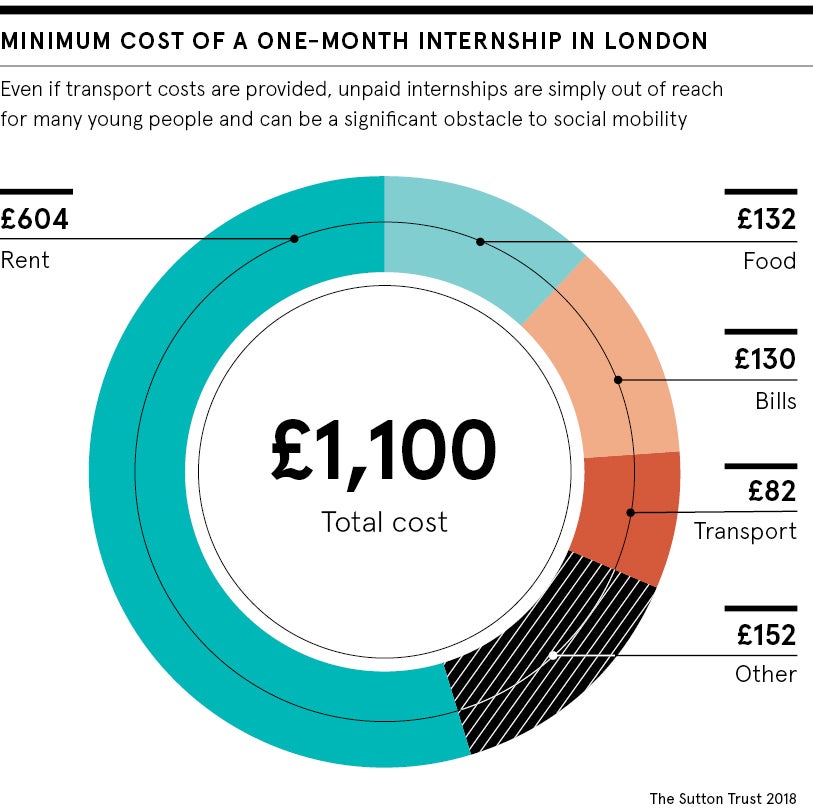

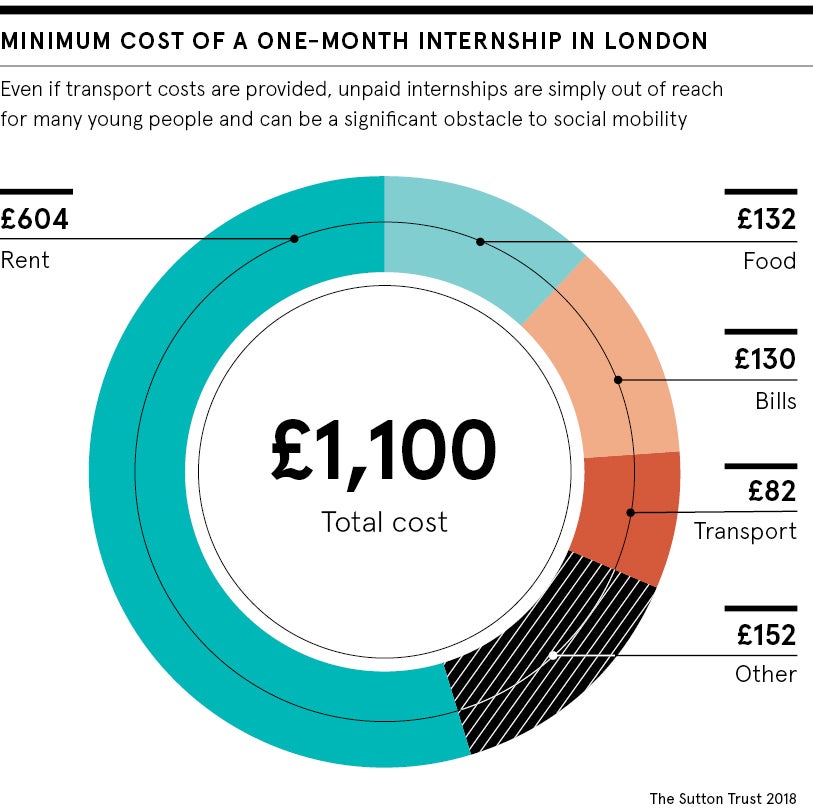

“For young people trying to break into the fashion industry, taking on an unpaid internship is often their only route in. The sheer prevalence of them is a major roadblock to improving social mobility,” says Rebecca Montacute, author of the report, which found that it costs an intern £1,100 for every month they work unpaid in London.

“These sums are out of reach for anyone without family who can foot the bill,” adds Dr Montacute. “Our research found high levels of social segregation in the industry, with working-class graduates substantially under-represented.”

Those who look, feel and sound different to us are probably the greatest gift the fashion industry could ever receive

Protesting unpaid internships can jeopardise interns’ futures

Legally, an intern’s rights depend on their employment status. If an intern is classed as a worker, asked to commit to set hours and perform the same tasks as a member of staff, they’re due the national minimum wage. But employers don’t have to pay it if an internship only involves “work shadowing”. Not only is this a huge grey area, but carrying out work is one of the main reasons for taking up an internship. Who wants to photocopy when they could write?

“Things are changing, but it’s long overdue,” says Tanya de Grunwald, founder of careers blog Graduate Fog and a campaigner for fair internships. “Although the law is on interns’ side, the complaints process means the weight of responsibility is on former interns to take action against their employer once the unpaid internship is completed, something few are willing to do, as they need a reference.”

One fashion merchandiser, who completed a paid six-month placement at Stella McCartney two years ago, says she regularly worked 13-hour days and most weekends. “I was burnt out at the end,” she recalls. “I had to get additional financial help from my parents. And it’s not just the placements themselves that make you think twice; there’s no guarantee of getting a job afterwards, so you don’t know how long you’ll have to live this way.”

A statement from Stella McCartney says the designer label, which recently launched diversity bias training across its global business, last year began working with The Girls’ Network, a charity that partners girls from disadvantaged communities with a professional, female mentor.

The culture of unpaid internships is damaging the fashion industry

Luxury online fashion retailer Matchesfashion.com says it ensures there is a clear structure in place for developing young people and is looking at new ways to attract a diverse pool of talent.

“We offer an annual paid internship where candidates are paid above the national living wage,” says Heidi Coppin, chief HR officer. “They enter the business as an entry-level employee so are entitled to the same level of care, support and company benefits. We only accept applicants who are in their sandwich year at university. What we have seen is that this is a really nice way of framing what an internship is about and we often go on to hire people once they have finished their degree.

“This year we are partnering with the Mayor’s Fund Access Aspiration work experience programme, where we take on four students from underprivileged backgrounds who wouldn’t necessarily have the means to find their own work experience.”

This is key. Working with external partners helps to get the word out that opportunities beyond unpaid internships exist. That’s why Ms Storr is also working with the Prince’s Trust, on-the-ground organisations and using social media to get Cosmopolitan’s scholarships in front of as many people as possible.

“We need to dismantle the cold, cool image that some of the fashion industry has and still insists on creating. Most of the people I know who work in it are incredibly warm and funny and down to earth,” she says. “But from the outside it doesn’t always look that way. It looks perfect. And perfection is intimidating if you’re a kid from Salford, like I was, looking out at this world.”

Unpaid internships have long been a staple for the arts

Protesting unpaid internships can jeopardise interns' futures