If recent clickbait headlines are to be believed, robots are already taking over our schools, relegating “Sir” or “Miss” to the status of a second-rate computer dumped at the back of the class.

Yet to many experts, the real value of artificial intelligence (AI) to education may be far more humdrum as a back-of-house tool to free up time for human teachers to build students’ social skills, resilience, appetite for learning and character.

Schools need to take more advantage of AI’s teaching capabilities

Miles Berry, principal lecturer in computing education at the University of Roehampton and a key architect of the national curriculum for computing, introduced to replace ICT four years ago, is disappointed at how few schools have exploited the new programme fully.

“AI is difficult to teach and schools either lack relevant resources or don’t know how to apply them, but in order to plug the technology skills gap, we must give our youngsters time to experiment with creating rudimentary chatbots for example,” he says.

“Setting up a Google Assistant, Apple Siri or Amazon Alexa and getting it to answer some of the questions that come up in a lesson would be a fairly simple task for many computing teachers, but to get them on-side, we need to talk far more about the role of machine-learning and far less about the dawn of the robots.”

While Mr Berry agrees that for now at least, AI is better suited to subjects with right and wrong answers than to teaching the nuances of Shakespeare, or even sport, its ability to relieve pressure on teachers is, he says, “unignorable”.

“Machine-learning can already play a vital role in setting work, in marking and assessment, and can track individualised learning very proficiently. If schools harness this power to its fullest extent, our human teachers are free to concentrate on the softer skills that are so vital to our employers,” says Mr Berry.

As a result of AI not being on the core curriculum, finding time to dedicate to it in the classroom is a challenge and this is partly why adoption has been slow

While growing numbers of primary, as well as secondary schools, are now teaching their pupils how to code, this is only one tiny element of AI and a skill which will be “old hat” by the time they enter the workforce, says Professor Rose Luckin of University College London’s Institute of Education.

One of three expert witnesses invited last year to attend a House of Lords Select Committee session on AI education and digital skills, she argues that “overall computational thinking” is far more interesting and creative than the term “coding” would suggest.

“I have nothing against coders, but it’s the easiest and arguably the least interesting aspect of AI, and one which deters many people, including women, from joining our tech companies at a time when we desperately need their skills,” says Professor Luckin.

“When it comes to equipping our youngest children for a world where AI will be enormously influential in their working lives and at home, the vast majority of our schools aren’t even at first base yet.”

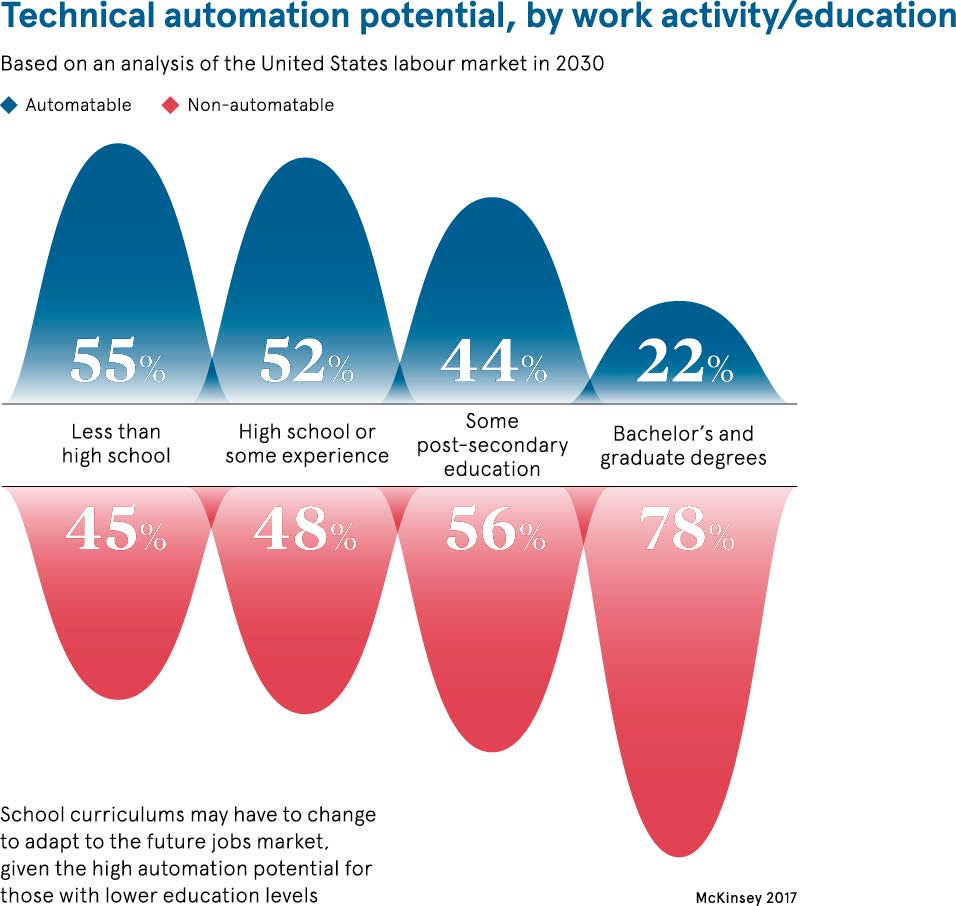

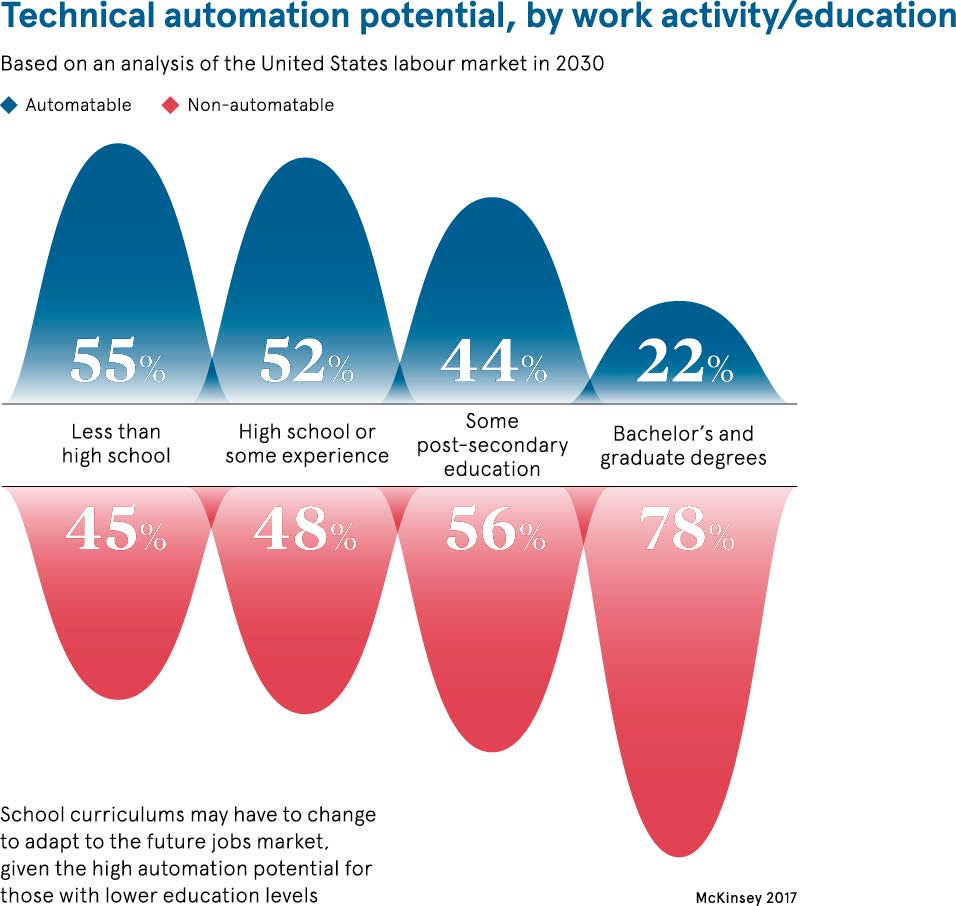

Some manufacturing roles could be obsolete in the coming decades as automation takes hold.

While Professor Luckin can’t comment on whether staffroom Luddism or apathy may be factors, she does believe that the scarcity of teachers with a grasp of AI is becoming a serious problem and calls for far closer collaboration between tech firms and educators.

“Some schools are drafting in tech experts to help introduce AI to the classroom, but this often fails because they don’t create materials that work in a classroom setting and they don’t know how to teach people,” she says.

“It would be unthinkable for the medical profession, say, to introduce AI without the direct input of medics in the actual development of resources and exactly the same should be true of education. Teachers don’t need fancy equipment, they need easy-to-use, easy-to-explain materials which don’t necessarily require a tech person to be in the room.”

Tailoring education for future workplaces

IBM developer Dale Lane, who helped create the educational tool Machine Learning for Kids, believes that while the “most critical aspect of AI education is helping teachers to improve their own skills and educate our children more effectively”, this continues to be overlooked. He shares Professor Luckin’s frustration over the lack of progress so far.

“As a result of AI not being on the core curriculum, finding time to dedicate to it in the classroom is a challenge and this is partly why adoption on the ground has been slow,” he says.

“Where IBM has had more success has been with activities which include elements of AI in non-computing subjects; for example, getting kids to train a chatbot to answer questions on the Vikings or using ‘text classifiers’ to understand how different newspapers report on the same story.”

Former teacher Tom Ravenscroft, founder and chief executive of Enabling Enterprise, which aims to bring the world of work into the classroom, has a very different perspective on the nature of the UK’s skills gap to that held by Mr Lane.

“The qualities which employers across every sector crave above all others, including tech skills, are those which are essentially human, including persuasive presentation and interpersonal skills. However hard some people may try to argue this, these abilities cannot be taught by machines,” says Mr Ravenscroft.

“While I would agree that there is a role for AI in the classroom, the biggest skills gap in the UK is not related to our interface with robots or our ability to code, but in our day-to-day dealings with other human beings.”

Thanks to their familiarity with computer games, children are less apprehensive than their parents about letting a computer mark their work or provide feedback

Mr Berry stresses that despite AI having no official place on the school curriculum, its applications are already making their mark on the lives of learners.

“Google Translate is helping millions of students whose first language isn’t English and, at a very basic level, spelling and grammar correction is making the polishing of our prose easier for all of us,” he says.

“AI can present information and provide practice time and time again, without becoming impatient or judgemental. Thanks to their familiarity with computer games, children are less apprehensive than their parents about letting a computer mark their work or provide feedback.”

Although Mr Berry believes that the biggest names in tech, including Microsoft and Apple, are “very generous in sharing free content with schools”, one man with a foot in both business and education camps believes industry can do more to help.

AI can present information and provide practice time and time again, without becoming impatient or judgemental

Paul Drechsler, chairman of Teach First and president of the CBI, says: “All of us would agree that our young children need to be properly equipped to enter the workforce of tomorrow, and I would urge all businesses both inside and outside tech to look again at what more they can do to provide knowledge, support and funding to teachers and pupils.

“If we accept that one day computers are going to be far better than we are at processing all forms of explicit knowledge, including literacy, numeracy and languages, we see the real AI challenge isn’t about creating more computer experts, but about building the skills which machines cannot emulate.

“Teamwork, leadership, listening, staying positive, dealing with people, and managing crisis and conflict are know-how skills, not know-what skills, and that’s where we humans will always triumph. But we need teachers, businesspeople and policy-makers to be in the same room to develop an education strategy appropriate for the next generation.”

Schools need to take more advantage of AI's teaching capabilities

Tailoring education for future workplaces