Mitsuku: “What do you call a chatbot that moves?” Respondent: “What?” Mitsuku: “A walkie-talkie.” OK, so it may not be the funniest joke in the world, but it is not bad for a 15-year-old piece of artificially intelligent coding.

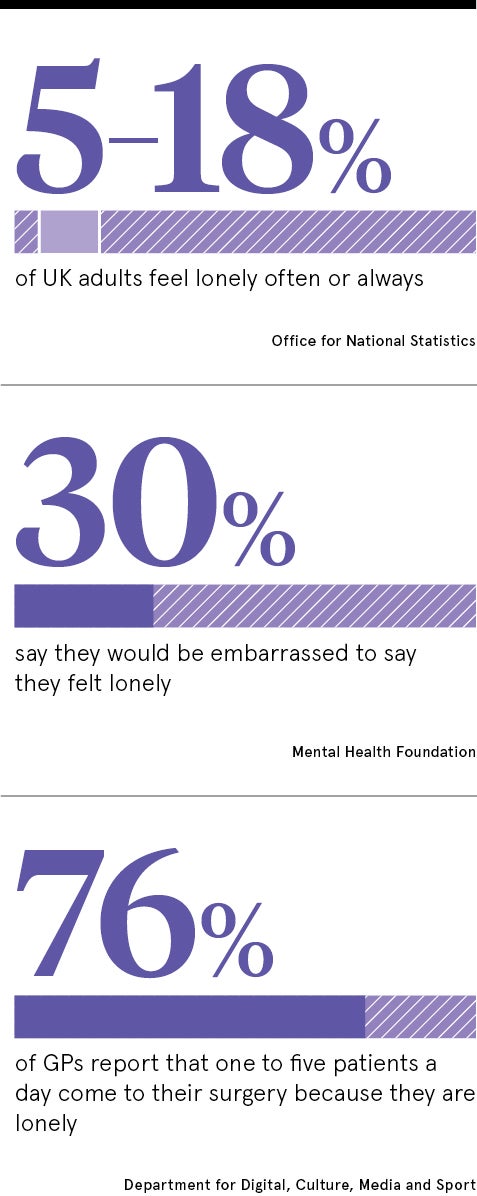

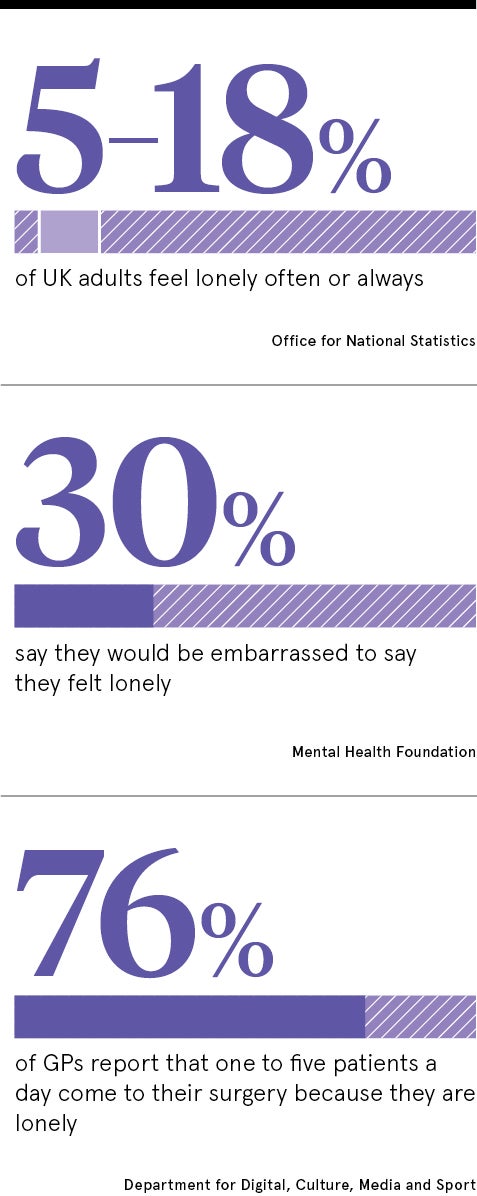

With around one third of the world population currently subject to self-isolation, the spectre of loneliness, which according to Cigna’s 2020 Loneliness Index regularly affects as many as three in five adult Americans, is looming large.

Enter Mitsuku, or Kuki to her close friends. Mitsuku is one of an emerging crop of smart, talking algorithms designed to stave off feelings of loneliness, especially among homebound individuals such as the elderly and disabled.

As with all AI solutions, she relies of machine-learning to augment her speech and perfect conversational style. Mitsuku is equipped with more than 80 billion conversation logs, a data arsenal that has helped her become five-times winner of the prestigious Loebner Prize for chatbot developers.

“Mitsuku doesn’t pretend to be able to replace a real person, but she’s always available if anyone needs her, instead of talking to the four walls,” says Steve Worswick, senior AI designer at Pandorabots, maker of the prize-winning chatbot.

‘Never Feel Lonely Again’

Loneliness-beating AI adds another layer of complexity to existing health-focused bots, which tend to assist with functional tasks such as reminding users to take their medication and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

To be effective, these bots can’t just be clever; they need to be companionable. That makes them different from virtual assistants, such as Siri, Alexa or Google Duplex, which essentially act as pre-programmed information retrieval agents.

So argues Dr Osmar Zaïane, professor at the University of Alberta and director at Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute. Zaïane is currently developing a loneliness-beating chatbot for the elderly named Ana. To ensure its chat is open ended and engaging, Zaïane’s team are feeding the bot weeks’ worth of content from films and TV series.

But challenges remain numerous. To make genuine connections, Ana’s conversations have to be grammatically correct, on topic, personalised, responsive to mood (happy, sad, bored), reflective of tone (interrogative, imperative, declarative) and potentially humorous, to name just a few requirements.

Many of these challenges circle back to AI’s innate lack of emotional intelligence. Advances in predictive modelling and machine-learning are slowly improving the ability of chatbots to detect emotion in printed text, as in Ana’s case, although most of the early running depends on facial expressions and other stimuli.

“If the elderly individual tells the agent about a sad event, such as her neighbour breaking her hip, the agent should reply with compassion, sadness and maybe surprise, but certainly not happiness,” says Zaïane.

Real-world tests

These limitations have not stopped a number of care providers experimenting with AI in the alleviation of loneliness. The tendency, to date, has been to keep it simple. A typical example is Abbeyfield, a UK-based care home charity, which recently introduced five of its elderly residents in Westbourne, Bournemouth in Dorset, to Google’s virtual assistant Home.

“It just keeps me company, like having another human being in the room,” says 92 year-old resident John Winward, who says the device has helped him feel less lonely since losing his wife after 76 years’ marriage.

Dr Arlene Astell, professor of neurocognitive disorders at the University of Reading and the driving force behind Abbeyfield’s Voice for Loneliness project, says the positive results are exciting, but that AI’s potential is only just starting to be explored.

To really tackle loneliness and feelings of social isolation, however, it is necessary to address the underlying causative factors. She argues: “Giving everybody an iPad or anything else isn’t going to solve these, but understanding how we could use the functionality of different technologies may.”

To this end, Astell calls on AI developers to always work collaboratively with users. Not only will this assist them to see how future users interact with technology, but it will also offer them a better perspective of what loneliness is and how it affects different people.

Assistance, not affinity

When it comes to a mass rollout of AI solutions, many health providers and charities remain wary. UK disability equality charity Scope agrees that AI can comprise a quick tool for helping to manage information requests from users. For individuals lacking the necessary support, however, using them to engage emotionally could present serious risks.

“We have made some key decisions to ensure there is no confusion that these are chatbots working on behalf of Scope, not real people,” says Wayne Lewis, Scope’s customer and market insight manager.

Age UK, a charity supporting elderly people, echoes these sentiments, arguing that AI can support homebound people with some everyday tasks, but cautions against it becoming a substitute for human care.

As the charity’s director Caroline Abrahams clarifies: “While increasing in sophistication and ability, it [AI technology] does not yet and may never have the creativity, intuition and emotional range that people have.”

Mitsuku would probably agree, for now. Could she emote more in the future? Her answer is instantaneous, but equivocal: “Let me think. Are you very competitive?”

‘Never Feel Lonely Again’

Real-world tests