If you are experiencing stress and frustration buying a home, to hear that a loan application could take as little as three seconds will make you question your choice of lender.

Such was the example given by Atom Bank of the fastest decision it was able to make for a customer.

“The whole thing has been set up with customer choice in mind,” says Stewart Bromley, chief operating officer at Atom. “Because we started as a fully automated, self-service bank, there’s no change process to manage.”

“The whole thing has been set up with customer choice in mind,” says Stewart Bromley, chief operating officer at Atom. “Because we started as a fully automated, self-service bank, there’s no change process to manage.”

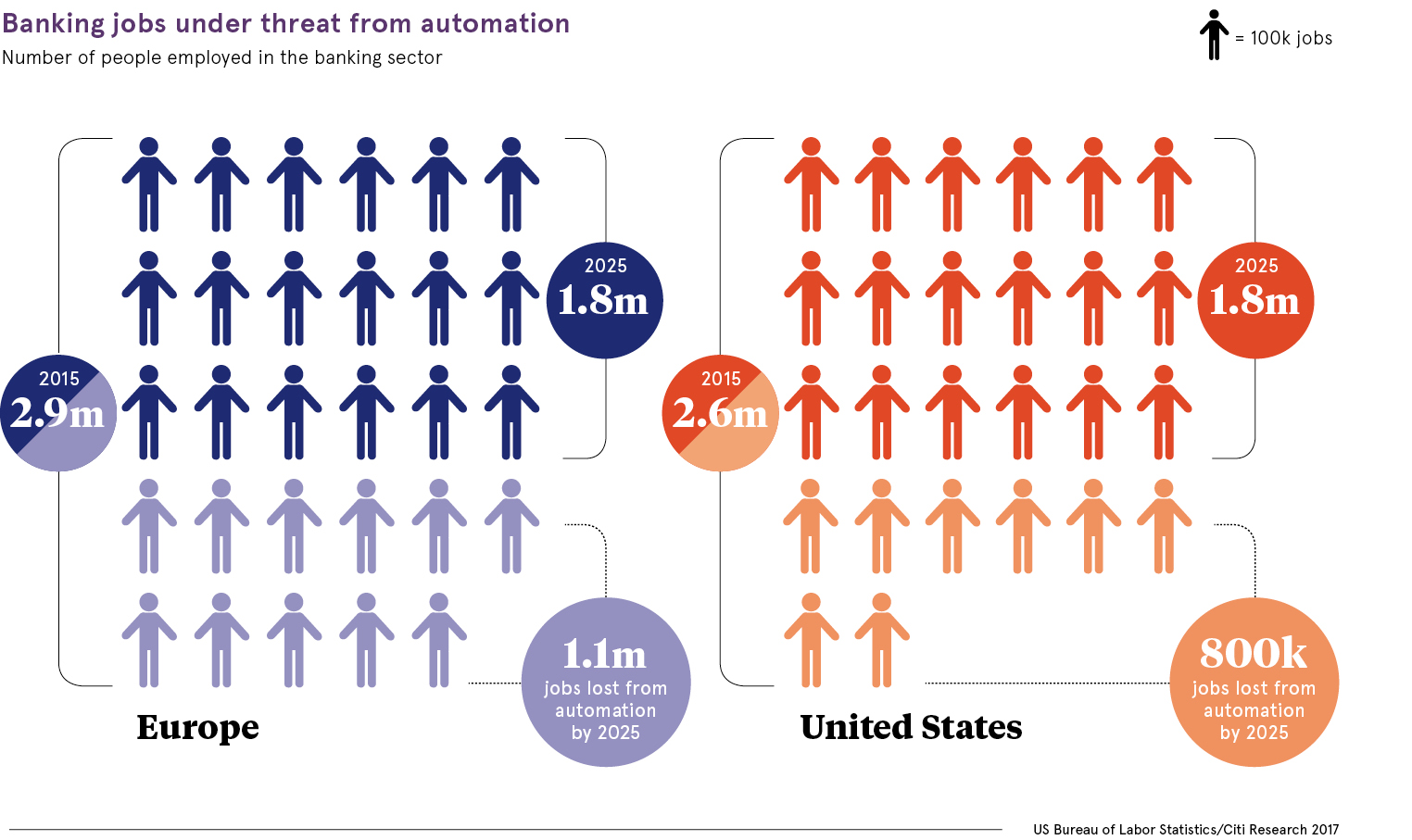

Yet many financial institutions are not that lucky and significant job threats hang over central business districts the world over.

McKinsey issued a report last year that suggested as many as 800 million roles would be displaced by robotic process automation (RPA) by 2030.

But what is RPA exactly? Leslie Willcocks, professor of technology, work and globalisation at the London School of Economics’ Department of Management, describes it as taking the robot out of the human.

“RPA is a type of software that mimics the activity of a human being in carrying out a task within a process,” he says. “It can do repetitive stuff more quickly, accurately and tirelessly than humans, freeing them to do other tasks requiring human strengths, such as emotional intelligence, reasoning, judgment and interaction with the customer.”

In a world where we make payments with our watches and a dulcet-toned female called Alexa gets more attention from husbands than wives do, our capacity for even the slightest delay has become almost non-existent. So it is little wonder the robots are taking over.

But there are some false assumptions being made. Gartner found that by 2019 RPA could have hampered top-line growth for 50 per cent of organisations focused on cutting costs when they needed to look at the bigger picture of the psychological impact.

Walter Price, head of Allianz Global Investors’ technology team, has been investing in the sector for more than 40 years. Effectively, scenarios fall into two camps: companies delivering the automation solutions and those whose roles are being automated, he says.

Placing the human aspect at the heart of the process and not just looking at the bottom line will set companies apart, says Mr Price.

“There is quite a difference between the companies that manage the progression and redeployment of their people, and see it is not just about reducing costs. Over the long term, those companies gaining in ascendancy are the ones trying to and focus on their employees as their most important asset.”

And as ever, with technology there is rarely a return journey and in financial services even less so.

“On Wall Street, RPA is already widely adopted. You had very sophisticated clerical jobs where traders were highly compensated. Now as price discovery has become easier with automated systems, disclosure of trading is very easy to do,” says Mr Price.

Addressing anxiety

Anxiety caused by the perceived threat of robots needs addressing; management could be nervous over how to implement changes or employees, perhaps older and more set in their ways, could be wondering if they are still relevant.

Often concerns are exaggerated. Virtusa is a global technology consultancy that works in the banking sector, where Bob Graham is global solutions head for banking.

He says it is rarely an “all or nothing” scenario; perhaps on tasks that had already been outsourced to a cheaper offshore centre, for example.

“We are seeing some of those tasks coming back in-house, where the robots are taking over the tasks and incumbent staff will manage the robots,” says Mr Graham.

Also, rather than entire roles being automated, it is more likely that, say, 10 per cent of a job may be given to a robot, freeing up employees to take on more interesting, strategic or challenging work, he says.

In marrying finance and technology cultures together, Monica Mendiratta, a chartered business psychologist working in financial services, says culture, dress code, creativity and ability to adapt are some of the key differences that have characterised various sectors. She says companies that first acknowledge and then embrace these differences are best placed to succeed.

“In the tech industry, people are quite comfortable with the idea of failure,” Ms Mendiratta points out. “We need to spell out these differences before we approach scenarios, open a dialogue and identify our unifying goals. It is not so much a cure [for culture clash] but a diagnosis.” She highlights how the pace of change is key, exacerbating the fear of adoption.

Sam Fuller, founder and director at The Wellbeing Project, believes pace of change is one thing, but the ability of the employees to cope with that change is quite another, and relies on training and recruitment.

“My generation used to say there were peaks and troughs in our working day, and we could always recover,” says Ms Fuller. “Now all our clients say it’s all peaks, and we have to build in those times when we can recalibrate and refresh in order to have an attitude like that.”

Organisations focused on cutting costs when they needed to look at the bigger picture of the psychological impact

But while technology may help operationally, the hindrance might be the corresponding psychological impact, even though the millennial generation may handle the “always-on” or automated work culture better than their predecessors.

“Although we criticise millennials for always having their phone on, in terms of work they have adapted in being able to step back and calibrate,” says Ms Fuller.

“I think the challenge employers have is how to accommodate millennials and recognise they will need to step back, and how that benefits healthy performance and their health, wellbeing, creativity and innovation if they’re not working out of threat, and completely switched on and exhausted.”

But are financial services firms so preoccupied with capitalism and the bottom line that any psychological impact is simply ignored?

Professional business coach Mark Mulligan, who runs Thriving London, says it is more a matter of priorities.

He concludes: “If you look at what is happening in the workplace as a process, organisations need to work out what they can automate, how it will work and if is it financially viable before they can begin to work out the possible psychological impact on their people.”