Using passwords to access our online lives is a commonplace experience and so are the attendant frustrations. Cybersecurity demands evermore complicated formulas: passwords might necessarily be of a minimum length, use a capital, number or special character. There is the regular insistence that a password be updated and not just to one slightly different or back to one you’ve used before.

“The good thing about passwords is they’re easy to use and, if compromised, easy to replace,” explains Mariam Nouh, researcher in cybersecurity at the University of Oxford. “There are no compatibility issues. You don’t need extra hardware. And business likes them because their use can be implemented cost effectively. The problem though is they can be compromised in so many ways.”

Certainly, while attempts at cybersecurity breaches may be increasingly sophisticated, the fact is passwords butt up against human psychology or, more specifically, memory. There are only so many discrete passwords an individual can retain without the security no-no of writing them down, which is one reason for the rise of password vault software.

The result is, when possible, the use of familiar, emotionally significant phrases, which is to say utilising the same mechanisms behind how humans remember a lot of things. But the familiar makes it easier for hackers to crack the password.

Leaving personal data exposed

According to a 2018 survey by password management company LastPass and Lab42, 59 per cent of respondents use the same password across multiple accounts. A majority of people would only go through the bother of updating their passwords if they were hacked; after all, they seem secure until that point. But then, according to a 2019 study by Verizon, 80 per cent of hacking-related security breaches are a result of weak or compromised credentials.

We’re going to use passwords for some time because, from a security point of view, the whole system out there is just so complex

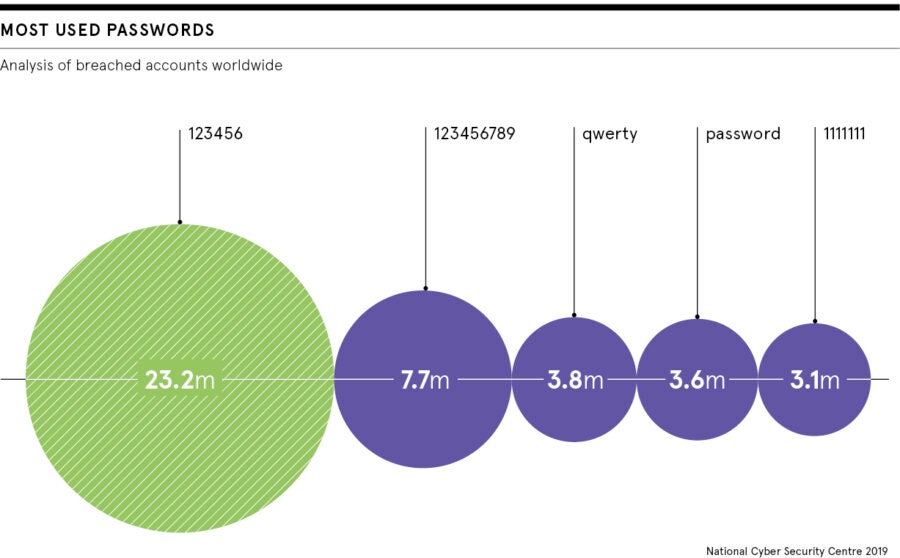

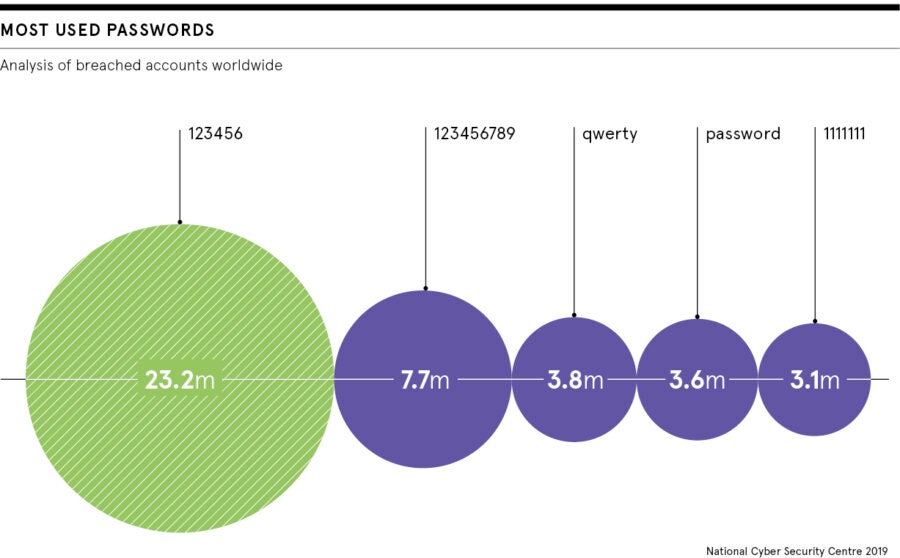

When LinkedIn suffered a data breach in 2012 and some 117 million passwords were compromised, many were revealed to be rather obvious. Among those used hundreds of thousands of times were “123456”, “linkedin” and “password”.

“There’s a lot of dissonance between how we know we should use passwords and how we actually do,” says Rachael Stockton, senior director of product at LogMeIn, makers of LastPass. And it’s not just a matter of memory. “A lot of our customers are just after simplicity, less time-wasting and more productivity. And we’re going to need more simplicity [in our password management] because the number of accounts we each use on the internet is only going to increase,” she says.

Getting educated about data security

That most of us don’t make much effort with our passwords isn’t just our fault. Arguably, security software design has failed to take human psychology into consideration.

“The industry has not done well in educating consumers how to use passwords,” concedes Rolf Lindemann, vice president of product at Nok Nok Labs, an authentication software vendor. “The result is this trade-off between security and convenience. That’s the dilemma.”

And especially given that the vast majority of websites still use passwords. It’s estimated there are now some 300 billion active passwords. Even Fernando Corbato, the man who pioneered the use of the password online, has described the situation as a “kind of nightmare”.

There have been new kinds of passwords proposed. Because people recognise pictures better than they remember words, so-called graphical passwords request users click certain points on an image in a certain order. The number of possible points essentially makes each user’s sequence unguessable. The efficacy of this approach is still being worked out.

But the likes of George Waller, co-founder of StrikeForce Technologies, a US startup with a number of patented cybersecurity inventions under its belt, argues the problem isn’t with passwords per se. Although he points out that most online businesses typically want to offer consumers the path of least resistance to gain access to their sites. The problem is with passwords’ delivery to servers down the line.

“Ultimately, it’s not really a matter of whether we use passwords or not, or whether or not you enforce stricter policies on their use. It doesn’t matter so much what you type in because there typically isn’t encryption at the key-stroke level and data is in transit [and so vulnerable] from the time you start typing your password,” he says. “We’re going to use passwords for quite some time because, from a security point of view, the whole system out there is just so complex.”

The future of the password

So does the password have any future, especially given the advent of the internet of things, which only looks like making cybersecurity breaches more widespread? “Passwords won’t go away completely, but I think we have to expect more multi-factor authentication, though that still needs to be convenient to use, while offering a sensible level of security to carry the public with it,” says Oxford’s Nouh.

This layered security approach is unlikely to come in the form of biometrics, which are themselves not completely secure and, when stolen, irreplaceable, unlike a password. Or at least not just biometrics. What’s needed, Lindermann contends, is however secure sites are accessed, we’re tied to a device that can be used to identify us. And this is a device most of us already carry and increasingly use to access the internet anyway: our smartphones.

We’re increasingly used to receiving confirmation text messages when working through security. But now such devices also operate their own fingerprint or facial recognition systems. Features limited to high-end, expensive phones just five years ago are increasingly commonplace and accessibly priced.

Since Microsoft launched its Windows 10 operating system last year, such password-free authentication is starting to come to desktops too. Device geolocation – if users are willing to share such information – is potentially another added layer of security.

Indeed, in a sense this more efficient device-led proposal is akin to the way in which an ATM requires both PIN number and the physical bank card. Or the way in which Estonia, for example, has developed its e-Identity system, which provides all citizens with a chip-and-pin e-card designed to authenticate an individual’s digital identity.

Making account access simple

Lindermann says: “It’s a matter of leveraging these devices in the right way and in a consistent way; one that allows users to chose the modality – they can still use a PIN if they’re not comfortable with trusting their biometrics [to a third party] – but which ties their identity to the specific device, a capability that can be off-loaded to devices we don’t own on the rare occasions that’s needed. It works because people want a much easier engagement with business that have secured sites and the ease of use is better for business too.”

Andrew Shikiar agrees. He’s the executive director of the FIDO Alliance, a consortium of tech security companies pushing for the creation of an industry standard to address security interoperability between devices and so far supported by big guns the likes of American Express, Amazon and Google.

“Passwords are the tip of the spear of the data-breach problem,” says Shikiar. “But the fundamental problem is the [online security] architecture itself. Using devices would not only give a better user experience – people are already used to unlocking their phones using biometrics – but it would get rid of scaleable cyber attacks. It would necessitate a behavioural change, but we have to break our dependence on passwords.”

He’s betting on that happening soon. He reckons the majority of mainstream consumer services online will have a password-free means of accessing them within five years.

Leaving personal data exposed

Getting educated about data security