Massive cyberattacks appear to go in waves and we’re probably due one soon. Marriott, British Airways, Facebook, Dixons Carphone are just some of the big names that have been smacked hard in the corporate face after a data breach. Bruising data haemorrhages seem to be a regular occurrence, while the dreaded fallout on social feeds, tabloid headlines and 24-hour online media can be legion.

“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more” is not so much a line from Henry V and the Bard himself, but more a 21st-century hue and cry from the public relations, C-suite and cybersecurity teams as they clamour to shore up tattered brand images and stymie any financial losses.

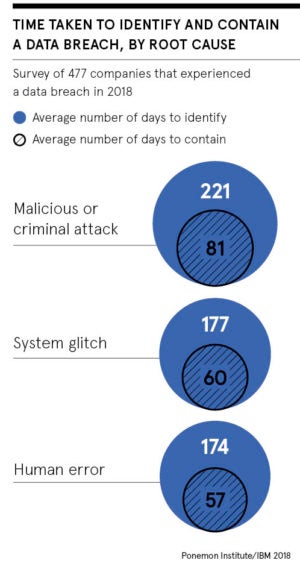

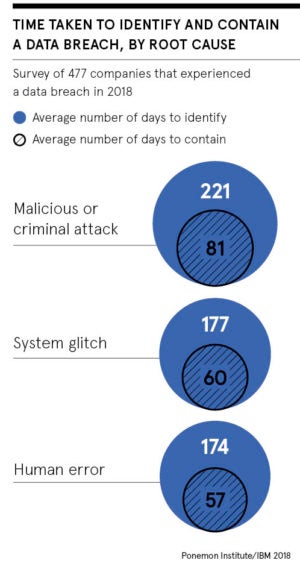

“One of the first challenges in dealing with a cyberattack is time. Incidents can go viral and global in an instant. Organisations will be dealing with short timeframes to manage reputational risk, recover data and prepare a co-ordinated response to regulators, third parties and affected customers,” says Dr Paul Robertson, cybersecurity, privacy and resilience director at EY.

Timing is everything when dealing with data breach aftermath

We also have to face up to the fact we live in a post-GDPR world. Companies have 72 hours to fess up to a cyberattack or face crippling fines under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. As the clock ticks in those early hours, the pressure can be extreme.

We also have to face up to the fact we live in a post-GDPR world. Companies have 72 hours to fess up to a cyberattack or face crippling fines under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. As the clock ticks in those early hours, the pressure can be extreme.

“Consumers are becoming increasingly savvy about the value of their data. Transparency, particularly when responding to data breaches, will become even more crucial to business success in the future,” says Tim Rawlins, director at NCC Group.

There’s no doubt that a proactive response must be delivered alongside an honest plan to tackle a data breach, even if its knee jerk, otherwise it’s carnage.

“The saying that ‘a lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth has its shoes on’ is very real when it comes to social media. A misrepresentation of the facts can become a ‘fact’ very quickly and is then often picked up by traditional news sources,” warns Richard Horne, cybersecurity partner at PwC.

“Cyber-crises are also different to many others in that directly after the event, the affected organisation often has very few facts to work with. Maintaining stakeholder confidence when you have no facts is a challenge and especially because these facts can take days, weeks, even months to uncover.”

British Airways could have done more following their data breach

At the same time, we live in an era when there’s a toxic cocktail of high data breach fatigue among consumers and low public trust in companies that hold our precious data. Arguably, it’s how businesses have handled attacks globally that has led to this state of affairs.

“The reporting of incidents has generally been poor and often doesn’t highlight the real scope of a data breach, with incident reports littered with non-definite words such as ‘could have’, ‘might be’ and so on,” says Professor Bill Buchanan, cybersecurity expert at Edinburgh Napier University.

“In the case of British Airways, every customer should have stopped transactions on their credit card – in fact, it should have happened automatically – as the data breach involved virtually everyone who entered their credit card details on their website over the period of the hack.”

In the summer of 2018, the details of around 380,000 airline bookings were compromised when hackers obtained names, streets and email addresses, as well as credit card numbers, expiry dates and security codes; certainly enough information to steal from people’s bank accounts. In textbook style, British Airways immediately contacted customers when the data breach became clear.

“Within the incident report, you had to scroll down the page to see the advice related to credit cards. At the time, the announcement was your passport details were safe and that your card details were at risk. You can see that PR teams will try to soften the scope of a data breach, but this doesn’t help the media or the general public understand the scope of an attack,” says Professor Buchanan.

The next generation of cybersecurity needs to be driven by intelligence

Look closer and you may realise that our data infrastructure has been built using methods created in the 20th century and we’re now having to re-engineer our data-fed world to deal with security in the 21st, including the cloud, mass digitalisation of supply chains, the internet of things, robotics and artificial intelligence, as well as the merger between physical and cyber-realms, the so-called fourth industrial revolution.

Next-generation intelligence-driven security is needed. “Before a data breach, businesses struggle to know whether they need to invest and struggle to understand what the impact of inaction will be on their business. They know this after a breach, of course, but at which point it’s too late,” says Nigel Ng, vice president of international sales at RSA Security.

Many organisations are now being more proactive and less reactive. As Cesar Cerrudo, chief technology officer at IOActive, puts it: “This is no longer an IT issue, but a business imperative.” Although preparedness is more prevalent in the likes of say financial services than in healthcare.

One of the first challenges in dealing with a cyberattack is time. Incidents can go viral and global in an instant

The “Wild West” of data-handling needs to stop

Big companies now have so-called fire-response policies and cyberbreach simulations bringing IT, public relations and customer service teams together as they work on dry runs and responses. However, there’s increasing realisation that a more holistic approach is needed.

“Embedding security into an organisation’s DNA goes far beyond just raising awareness or training people; everyone needs to understand how the business decisions they make can impact cyber-risk,” says Mr Horne. However, this still doesn’t tackle the issue of reviving public trust, which is sorely needed before the next round of data breaches.

“It is often difficult to tell the difference between say a bank which invests heavily in their cybersecurity and one that doesn’t,” says Professor Buchanan.

“For those affected, it is often financial loss, which worries many people, and therefore we need ever-increasing levels of security. Our ‘Wild West’ of data-handling and data-mining needs to end sometime soon. Maybe there should be cybersecurity ratings for companies, where they would be extensively audited for the detection and response to incidents.” There’s a thought.

Timing is everything when dealing with data breach aftermath

British Airways could have done more following their data breach