The UK may be on the verge of a data centre construction boom, as a surge in the adoption of generative AI results in greater demand for power and compute resources. But the data centre industry is facing growing scrutiny from environmentalists, local residents and even investors, which threatens to scupper ambitious growth plans.

GenAI and its energy demands have yanked the bulky, boxy data centres out of relative obscurity and thrust them into the spotlight of public scrutiny. The hyperscalers – the large cloud computing service providers, such as Google and Microsoft, that are investing heavily in generative AI – admit the technology is resource-intensive. Google recently scrapped claims to carbon neutrality and conceded that achieving its net-zero targets by 2030 will be a challenge. In its latest quarterly results, investment in property and equipment – a large proportion of which will go towards expanding its data centre footprint – increased by $1bn (£778m) to $13bn (£10.1bn) between the first and second quarters of 2024.

As Labour enters government for the first time in 14 years, senior ministers including Angela Rayner, Rachel Reeves and tech secretary Peter Kyle have said the UK will relax planning restrictions on data centres and potentially intervene to override local opposition. The deputy prime minister has already stepped in to rescue the planning appeals of two data centres, in Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

In the UK, data centres have largely flown under the radar despite their enormous footprint. As recently as 2020, TechUK said the data centre industry’s “only shortcoming” was that “nobody seems to have heard of it”.

But awareness of the data centre industry – and its massive energy demands – is growing. Environmental campaigners and other activist groups in the US, Latin America and Europe have launched challenges against digital infrastructure providers. Given the mounting pressure on the industry, perhaps the public’s prior ignorance was no shortcoming at all.

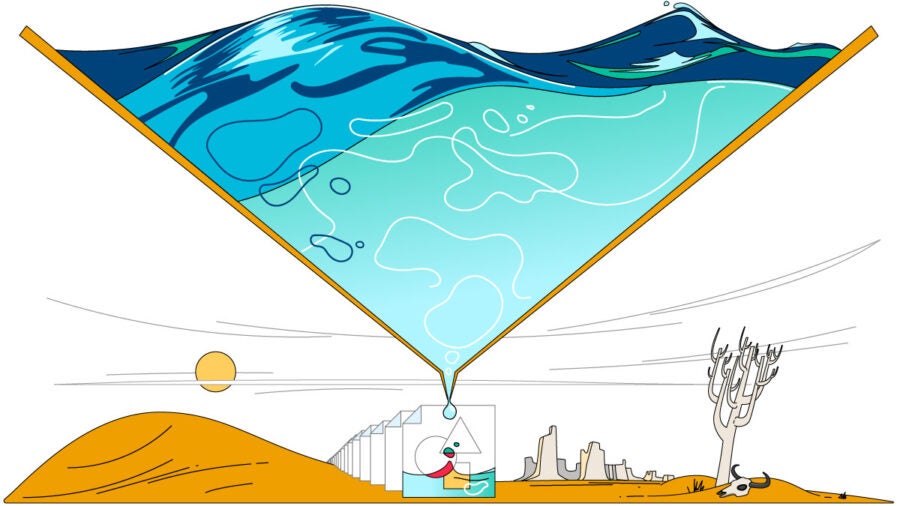

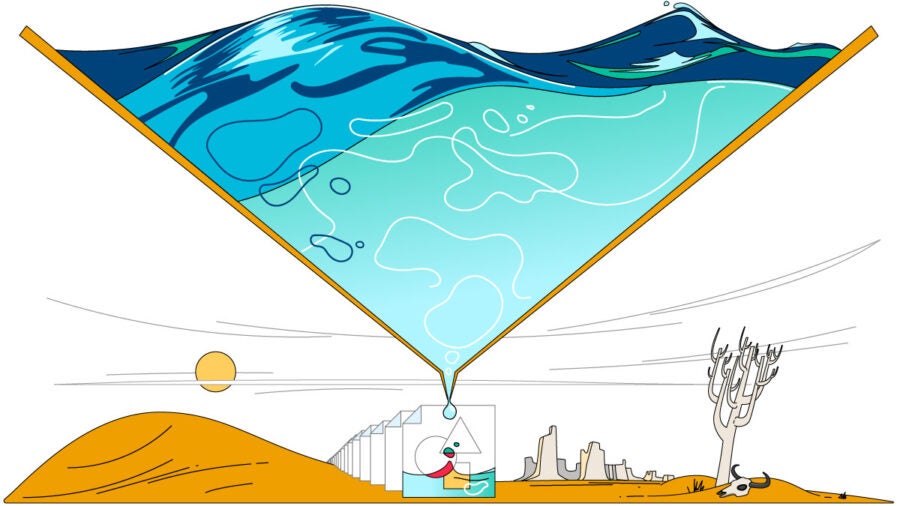

Although the government seeks to grow the UK’s data centre industry through international investment and policy shifts, this will require transparency, closer regulation and a commitment to involving local stakeholders. Failure to do so will risk repeating mistakes made elsewhere, where tech companies are pitted against citizens, who perceive the hyperscalers as little more than parasitic agents sucking up scant natural resources.

The UK data centre landscape: state of play

The data centre industry is not known for its glitz or showiness. After all, the largest development in the UK is a high-security area on the outskirts of Slough – a town that poet John Betjeman once called to be bombed.

The Slough Trading Estate, once a scrapyard for army vehicles, now hosts dozens of data centres, including those of infrastructure provider Equinix, and will soon host more.

The site – colloquially termed ‘The Dump’ by locals – even serves as a digital portal to the Americas, via wiring that runs from west London across England and through subsea cables in the Atlantic Ocean.

During Raconteur’s recent site tour of Equinix’s sprawling colocation facility, which the company describes as a “hotel for data centres”, its UK managing director Bruce Owen remarked on Britain’s historically strategic location, bridging Europe with the Americas.

“The UK has always been well positioned for international trade,” he says. “We should do everything we can to protect that. Today, now that everything has moved to digital, it manifests itself in data.”

The estate is the size of 326 football pitches, but Owen says its economic importance is perhaps exemplified by one small, unassuming building across the road in the meeting room of the LD6 facility. Inside this structure, servers process data for almost all of London’s foreign exchange and credit card transactions.

But, while the site’s economic and digital importance is unquestionable, there is another side to the story. In 2021, Slough effectively ran out of power. The construction of a new substation was required to meet the data centre’s growing electrical power demands.

In 2022, the Greater London Authority warned that the building of new houses in West London had been hampered by a lack of energy capacity, as power was guzzled up by nearby data centres. And in 2023, Thames Water threatened to restrict the water services provided to data centres if they did not curb their consumption.

When asked if the competition for power and utilities threatens nearby urban centres such as those in west London, Owen says: “I hope not.” But, he adds, ensuring the efficient allocation of resources is the job of local government.

Data centre activism: global outlook

While Slough is not yet at breaking point, globally, the competition between data centres and local communities for energy resources is causing conflict.

Data centre projects have inflamed tensions with locals, strained national grids, disturbed agricultural production and, in the case of Portugal, even toppled a government. Last year, prime minister António Costa was forced to resign amid allegations over corruption and influence peddling, relating in part to the €3.5bn (£2.4bn) Sines 4.0 data centre.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, agricultural groups are fighting the construction of new data centres. And, in the US, local politicians in states such as Arizona that are susceptible to droughts have used city ordinances to resist new hyperscaler developments on the basis of water conservation.

Hyperscalers are also facing backlash in Mexico, where the government is embracing a data centre boom even as its capital, Mexico City, risks running out of fresh water. A similar battle is being waged in drought-stricken Santiago, Chile where environmentalists and local indigenous groups are battling tech companies over their water consumption.

Every time a big tech company wants to open a data centre, they should be honest and clear about water and energy consumption

In a damning report for tech publication Rest of World, activists described the situation in Santiago as “extractivism”. Google, for instance, was granted permission to extract 228 litres of water per second for one of its sites, even as the city’s drought crisis intensified. The so-called Google Urban Forest – which the company built to offset air pollution from its complexes – is now shut to visitors. Reports indicate that the forest appears neglected and contains mostly dry or dying plant life.

Sebastián Lehuedé, lecturer in ethics, AI and society at King’s College London, believes that local participation in data centre policies is essential. “Otherwise, projects are going to take a lot of time,” he says. “If they go to court, the judicial process can take years.”

However, where there is participation from local communities, hyperscalers are not always transparent about the impact of their developments, according to Lehuedé. Sometimes locals perceive hyperscaler investment as an indicator of regional economic growth, he adds. While such impressions may be understandable in some cases, typically there is little public information about the environmental costs.

Moreover, sustainability information in annual company reports can be difficult to find or obfuscated. Plus, data centre providers will often use successful projects in one country to justify their operations in others where utilities infrastructure and supply chains are far more vulnerable.

“Every time a big tech company wants to open a data centre, they should work with communities – and be honest and clear about water and energy consumption,” says Lehuedé.

Opposition on the doorstep

Ireland’s Central Statistics Office reported that data centres accounted for 21% of the country’s total electricity usage in 2023 – more than all of Ireland’s urban homes combined.

“It’s an extraordinary figure for the 82 data centres in the country,” says Dylan Murphy of environmental campaign group Not Here Not Anywhere.

Initially, Murphy adds, many in Ireland welcomed the building of new data centres as a sign of investment and opposition was dismissed as parochial nimbyism. But attitudes changed as the impact on the grid became increasingly evident.

Ireland recently passed a partial moratorium on new data centres, but projects are still being approved. Providers in Ireland have also started applying for planning permission for their own fossil fuel-powered energy infrastructure, including on-site gas terminals. Although they lessen the burden on the grid, these initiatives are also “further contributing to Ireland’s emissions,” says Murphy.

According to Lehuedé: “The UK just has to look at what’s happening in Ireland to see what the future could be like, but it should also look at the activism emerging elsewhere.”

With data centre restrictions in Ireland threatening future developments, the industry is exploring options in other territories. Seeking to take advantage of the opportunity and boost the UK’s balance sheet, tech secretary Peter Kyle recently embarked on a fact-finding mission to the US, where he met with the hyperscalers to discuss barriers to data centre planning in the UK. Both Microsoft and Google are investing billions in new data centres across the country.

The UK just has to look at what’s happening in Ireland to see what the future could be like

There are clear inefficiencies to be addressed. Data centre planning rules are Byzantine. Despite the importance of data centres to the economy and their potential impacts – good and bad – approvals are managed by local governments.

The current rules involve a complex process that tends to vary depending on the local authority in question. For instance, parts of Greater London have different rules to Slough, where the complexes are clustered in a “simplified planning zone”, meaning permissions are pre-approved for certain types of projects. This zone in Slough, however, is set to expire in November 2024.

The planning process usually begins with a pre-application to inform the authority, just as a developer would with any new building. Next come discussions about environmental effects, building control, fire risks and the impact on local people.

The process typically requires a permit from the Environment Agency (guidelines here), while the availability of sufficient electrical capacity is a question for the developer to agree with the distribution network operator (DNO).

DNOs also vary by region. For instance, in Slough, Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks manages the borough, but the Slough Trading Estate is run by an independent DNO, Slough Heat and Power, which is a licence-exempt private network connected to Southern Electric Power Distribution.

Under the Conservative government, the Department for Science, Technology and Innovation (DSIT) considered re-categorising data centre sites as critical national infrastructure.

This would put data centres in the same category as hospitals and energy facilities, which would necessitate further central government involvement to enforce security and resilience requirements. It’s likely the new government will continue this work.

But even with more central government involvement, local participation will remain essential to protecting communities.

Data centre activism arrives in the UK

Just as Kyle was embarking on his fact-finding mission to the US, a confrontation was unfolding in the small village of North Ockendon, in the London Borough of Havering.

Sitting just outside the M25 and within the greenbelt – the protected patch of land encircling the ring-road that buffers London and the countryside – North Ockendon is perhaps an unlikely location for what may become Europe’s largest data centre complex.

Digital Reef, the developers of the proposed 215-hectare site, say it will be environmentally sustainable, unlike other “impact” data centres. They promise to create a new ecology park to correct damage to local wildlife, as well as a vertical farm, fuelled by the centre’s excess heat, to grow crops usually cultivated in warmer climates.

We don’t have a decent water supply anyway. There’s no way they’re going to get millions of gallons

But opponents insist that these promises amount to greenwashing and point out that Digital Reef has no experience building data centres. They also question how the settlement’s small country lanes will support the transportation of construction materials, how the complex’s energy and water consumption will impact their community and who will be responsible for maintaining the ecology park. Crucially, they worry that the data centre will irreparably damage the local environment and displace existing farms and crops.

Responding to claims of greenwashing, Digital Reef’s MD, Eleanor Alexander, says: “Our projects are a marked departure from the impactful data centres of the past and will set the standard for truly sustainable data centre campuses through the collocation of clean energy infrastructure, agri-tech and ecology.”

She continues: “As well as being net zero in operation, with zero on-site fossil fuel consumption, we are anticipating a biodiversity net gain across the site. We will be generating our own renewable energy on site, as well as enabling the delivery of 445MW of other renewable energy projects elsewhere due to our investment in upgrading Warley Substation. We strongly disagree with any claims of greenwashing and see the project as a global exemplar in sustainable development for the future.”

Despite the reassurances, residents remain sceptical. They claim the process has been opaque from the start and that the developers are making use of a so-called ‘local development order’, which they say leapfrogs the traditional planning process and places approval powers with the state instead of the local community. Some have even suggested the developer is taking advantage of Havering council, which was recently rescued from bankruptcy. Digital Reef has offered the cash-strapped council a £9m “development premium” for approving the site.

Ian Pirie, a local opponent of the development and coordinator of Havering Friends of the Earth, recalls: “Local residents asked the developer where they were going to get their water. They said they would use the local water supply and residents laughed. We don’t have a decent water supply anyway. There’s no way they’re going to get millions of gallons.”

Pirie is not against building data centres. He describes himself and others in his network as “realists” who “understand the need for data centres”. But they favour developments where there is pre-existing supporting infrastructure, such as the proposed site in the London Docklands. “We have argued: surely you can find brownfield sites, surely there are better places around London you can do this,” he says. “But they’ve told us they can’t find anywhere else.”

But Spencer Lamb, chief commercial officer of data infrastructure provider Kao Data, believes that building on green-belt land may not be necessary. He says Labour’s manifesto pledge to override local opposition to construction on the green belt may have been a reaction to opposition to one project, where opponents said a new complex would ruin views of the M25.

The real issue is how we power new data centres

Cathal Griffin, chief revenue officer at data centre provider Asanti, agrees, adding: “Until we have exhausted all the brownfield and decommissioned industrial sites, there may be no need to look to the greenbelt.” He points to sites such as the ex-nuclear power station in Dounreay as potential candidates for brownfield development.

“The real issue is how we power new data centres,” he says. “While there’s red tape and restrictions around where developers can build, it’s insignificant compared with the red tape around using private wires for green energy.”

A national data centre strategy

With a nationwide energy crisis, water restrictions in certain regions and the ambient threat of climate change hanging in the atmosphere, perhaps a more deliberate tack is needed.

Residents, environmentalists and many in the data centre industry seem to agree that data centres should be recast as critical national infrastructure, given their energy demands and their importance to the economy and national security.

Murphy, of Not Here Not Anywhere, says: “We would like to see more objective measures and checks and balances put in place. Part of getting that to happen is treating data centres like public utilities – like we view the internet in general.”

He points out that in many countries, internet infrastructure falls under the remit of a utilities regulator. Data centres, he argues, are a natural extension of this authority.

Lamb believes part of the problem is that data centre development in the UK has been ad hoc and uneven for the past decade.

“We’ve got almost 1GW of power being pumped into Slough, with these data centres are all very close to one another,” he says, explaining that the previous Conservative government was “not interested” in exploring a more deliberate national data-centre strategy because “they saw everyone getting on with it and it was working”.

But, in his view, national planning could help ease the burden on people and the grid, while strengthening the UK’s renewables sector.

It’s quite exciting that the industry could really fuel regeneration with renewables

Lamb suggests creating clusters in the northwest or northeast of England, adjacent to new wind farms that could be used to power them. This approach would underwrite the commercial model of the wind farm and also provide the energy needed to power the data centres.

“This would create a data centre industry for renewable energy products and a wealth of job opportunities. It’s quite exciting that the industry could really fuel regeneration with renewables,” he says.

“We could distribute this private investment across the country to places that really need it and will benefit from it,” Lamb explains. “We’d come up with a national data centre planning scheme, which provides special planning zones across the UK; in effect brownfield locations that have availability of power and local communities that can do with the investment.”

Owen, of Equinix UK, agrees that careful planning is essential: “Data centres should be planned in the same way that you think about planning cities around hospitals and other critical infrastructure,” he says. “I hope we don’t end up in a position where data centres are competing or constraining things like access to power, housing or hospitals. We would partner with the government to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

The UK government “recognises quite clearly” the challenges around distribution and future power needs, according to Paul Lowbridge, head of customer management at the National Grid. For this reason, the government has committed to a strategic spatial energy plan, which will identify where major sources of power generation should be located to meet demand forecasts for 2050.

The Labour government appears interested in creating a more deliberate data plan. The thinktank Tony Blair Institute for Global Change urged the government to consider a data centre policy resembling those in the Nordics and Singapore, the latter of which recently lifted a moratorium in favour of a new, environmentally sustainable data centre strategy.

Both Kao Data and Equinix confirmed that they are in conversations with the government about the UK’s data centre needs.

Kao Data has been consulted on strategic data centre initiatives, including AI-capacity planning, power provision and sustainability, while Equinix is working with the government independently as well as through the TechUK trade group.

Although government and industry maintain their commitment to sustainability, promises to make data centres more environmentally friendly should be thoroughly scrutinised so that they are not merely used as an excuse to break ground. They would have to be matched by action, perhaps with the creation of a new regulator to enforce mandatory reporting on energy use and forecasting.

The bad blood caused in Havering – and the wave of data centre protests erupting globally – underscores the critical importance of a national plan to engage with local stakeholders. For now, in that small settlement past the M25, residents remain committed to fighting Digital Reef.

The importance of data centres is not in doubt. But these vast, energy-hungry buildings – internally humming with servers and jammed with tangles of wires in brightly lit rooms – which house the building blocks of our digital lives, must operate with the consent and in the interest of those of us who occupy the physical world. Otherwise, providers may have a fight on their hands.

The UK may be on the verge of a data centre construction boom, as a surge in the adoption of generative AI results in greater demand for power and compute resources. But the data centre industry is facing growing scrutiny from environmentalists, local residents and even investors, which threatens to scupper ambitious growth plans.

GenAI and its energy demands have yanked the bulky, boxy data centres out of relative obscurity and thrust them into the spotlight of public scrutiny. The hyperscalers – the large cloud computing service providers, such as Google and Microsoft, that are investing heavily in generative AI – admit the technology is resource-intensive. Google recently scrapped claims to carbon neutrality and conceded that achieving its net-zero targets by 2030 will be a challenge. In its latest quarterly results, investment in property and equipment – a large proportion of which will go towards expanding its data centre footprint – increased by $1bn (£778m) to $13bn (£10.1bn) between the first and second quarters of 2024.

As Labour enters government for the first time in 14 years, senior ministers including Angela Rayner, Rachel Reeves and tech secretary Peter Kyle have said the UK will relax planning restrictions on data centres and potentially intervene to override local opposition. The deputy prime minister has already stepped in to rescue the planning appeals of two data centres, in Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.