In this digital era of exponential technological advancements, when science fiction is increasingly becoming science fact, there are bold claims that the next transformational tech will be the fifth generation of mobile networks. But who are the trailblazers?

“On the world stage, the United States and east-Asian countries like China and South Korea are the early winners in the race for 5G adoption,” according to Kamal Bhadada, president of communication, media and information services at Tata Consultancy Services. “Many operators in those markets have already made their 5G plans public and are moving to implement them across their networks.

We need to stop talking about the ‘race to 5G’, as 5G technology alone will not bring about any revolutions in society or industry

“Europe is also showing signs of playing an increasingly leading role, with 139 pilots running across 23 countries. Most European countries should have some access to 5G services by next year, which will help open up opportunities for innovation.”

This analysis is echoed by numerous experts. “It is clear that a lot of the initial drive to accelerate the impact of 5G will come from Asia where the high density of fibre networks and more modern infrastructure will enable some of the more advanced technology, such as millimetre waves,” says Paul Beastall, director of technology strategy for Cambridge Consultants and member of the UK5G Advisory Board.

Is South Korea leading the 5G race?

Guillaume Weill, head of telecoms at technology consultancy Intralink, says South Korea is leading the pack. “The country auctioned its first 5G licences last summer for $3.3 billion (£2.5 billion) and was one of the first to deploy a commercial 5G network. And in April, South Korea achieved the world’s first national consumer rollout of 5G,” he says.

That may be good news for South Korea-based electrical giant Samsung, which “is determined to secure a large share of the international 5G equipment market, having enjoyed just 3 per cent of the market share in 2018”, notes Mr Weill.

However, in terms of manufacturers of 5G-related products, Scandinavian brands Nokia and Ericsson, and China’s Huawei, are “the unequivocal market leaders”, says Daryl Schoolar, principal analyst at Ovum.

“They have the broadest product portfolios and global reach along with the strongest service support,” he says. “It is hard to imagine a scenario in which a mobile operator looking to deploy a new network does not reach out to at least one of these three vendors during the bidding process. Of the three, Nokia leads based on its combination of global reach, and breadth of portfolio and services.”

Opinions divided over Huawei’s supremacy

Huawei’s international reputation has been tainted by its links to the Chinese government. In early-May, for example, Gavin Williamson was sacked as prime minister Theresa May’s defence secretary over a leak from a National Security Council meeting at which officials discussed whether to give the green light to Huawei investing in the UK’s 5G digital infrastructure.

More recently, the Trump administration added Huawei to a trade blacklist, preventing it from doing business with US suppliers without government approval.

“Huawei’s competitiveness remains hampered by politics,” says Mr Schoolar. “Australia has joined the US in blocking its equipment. India did not approve Huawei for 5G trials and Japan is also sceptical. So, while Huawei is clearly the market leader in revenues and has a portfolio breadth equal to Nokia, its inability to sell in certain markets reduces its overall competitive position.”

William Webb, fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and chief executive of Weightless SIG, believes that elbowing aside Huawei could be beneficial for the UK and other countries in Europe that hitherto have relied on the Chinese manufacturer.

“Huawei is somewhat ahead of competitors, so not using its equipment will probably delay network rollout,” he says. “But this may be a good thing. It is generally the second mouse that gets the cheese in these situations and it is not clear that there are strong national reasons for early 5G deployment.”

Wider adoption of 5G should not be rushed

This could also play into the hands of Nokia and Ericsson that are now benefiting from being first to market with mobile in the 1980s and have developed key intellectual property rights. Their strong position is “partly due to history and partly due to the main focus of the mobile operators on 5G at present: the radio and hence the need to work with the main radio access network vendors”, says Ian Goetz, chief architect of mobile solutions at Juniper Networks.

Little wonder Nokia’s vice principal for networks, marketing and communications Phil Twist is trumpeting no fewer than 36 commercial 5G contracts with global operators. “We are approaching 100 engagements in total with communications service providers that are evaluating and deploying 5G,” he says.

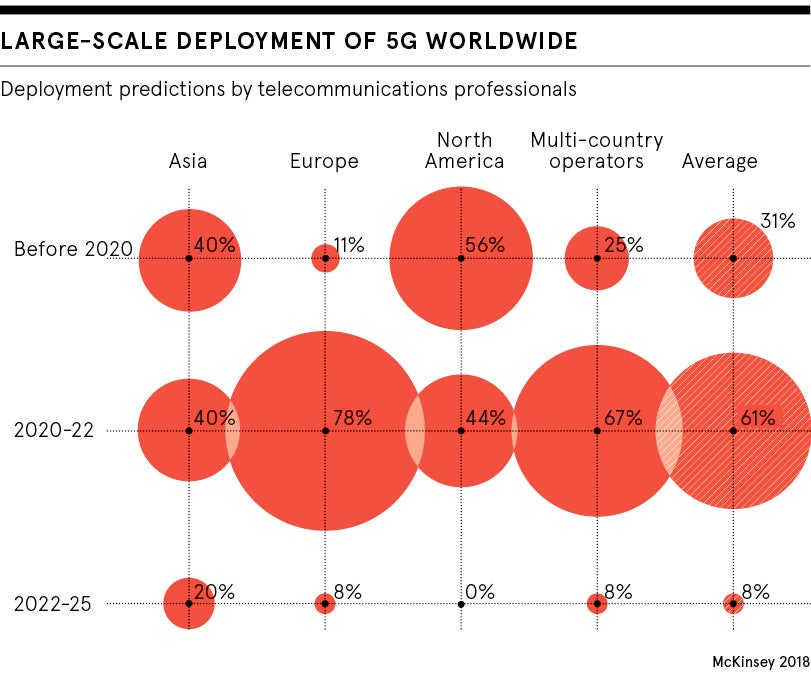

In February, prior to the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Nokia published the 5G Maturity Index. Reflecting upon the research, the organisation’s chief executive Rajeev Suri says: “Two things became very clear. First, the remarkable speed of initial pick-up. We spoke to 50 operators across every continent and we found they all planned to complete a limited commercial 5G launch by the end of 2020.

“The second big takeaway was that wider adoption would not be rushed. Most operators expect it to take about four or five years after that initial rollout to get 5G deployed to 75 per cent of their customers. And this cushion of time will be just as vital to 5G as its quick start.”

Should we really be racing to 5G at all?

So perhaps speed is not of the essence, after all. “We need to stop talking about the ‘race to 5G’, as 5G technology alone will not bring about any revolutions in society or industry,” argues Andrew Palmer, consulting director of telecoms at CGI UK.

“We need to work through the outcomes we wish to deliver, the sustainable use-cases that will deliver these outcomes, and the data and analytics required to support these use-cases. Only then should we worry about the technology that is required to support it.”

Is South Korea leading the 5G race?

Opinions divided over Huawei's supremacy