When most people think about artificial intelligence, their minds turn to glorified fights to save the human race from rogue robots, a familiar story played out on Hollywood screens in decades gone by.

While machine intelligence is still far from resembling human consciousness, an AI fight is playing out in real life, not between robots and humans, but rather among the businesses vying to lead an increasingly lucrative market.

The origins of AI stretch back to 1950, when computer science pioneer Alan Turing published a paper speculating that machines could one day think like humans. Last year, research firm IDC valued the market at $8 billion, forecasting a rise to $47 billion in 2020.

Between Turing’s landmark paper 67 years ago and today’s wild market valuations, most major AI developments have either fallen in the realms of research and academia or involved computers beating people at human games.

IBM won acclaim when its Deep Blue computer defeated chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1996 and 15 years later its next AI iteration, Watson, dominated human opponents on TV game show Jeopardy! More recently, Google stole headlines with the 2015 victory of its AlphaGo program over Lee Sedol, an 18-times world champion of the ancient Chinese board game Go.

AI today

In the last few years, however, AI has moved beyond research and televised standoffs between man and machine to become a technology used by millions of people every day, thanks to a trio of critical developments.

Firstly, the ubiquitous use of online services, smart devices and social media has made data available on a mass scale. Data is the fuel for developing algorithms for deep-learning, a form of AI that allows machines to learn and write software. The more data is fed to the system, the better it gets at performing tasks.

Hosting huge quantities of data was previously an extremely expensive undertaking that would have continued to hamper AI development had it not been for the advent of affordable, on-demand cloud storage from Amazon, Microsoft and Google.

Completing the trio was the development of more powerful chipsets, accelerating that process for training computers to think like humans.

All this means the great promise of AI can finally be realised in industries ranging from healthcare and energy to self-driving cars and manufacturing. The result is a race among the world’s largest technology companies to position themselves as a leader as AI applications become some of the most in-demand and lucrative products on the market.

Intel last month spent $15.3 billion acquiring Mobileye, an Israeli chip maker for driverless cars

The AI market

The significance of the AI industry can now be seen not just in the scores of enterprises beginning to deploy this technology at scale, but in the market performance of companies that are already enjoying its demand.

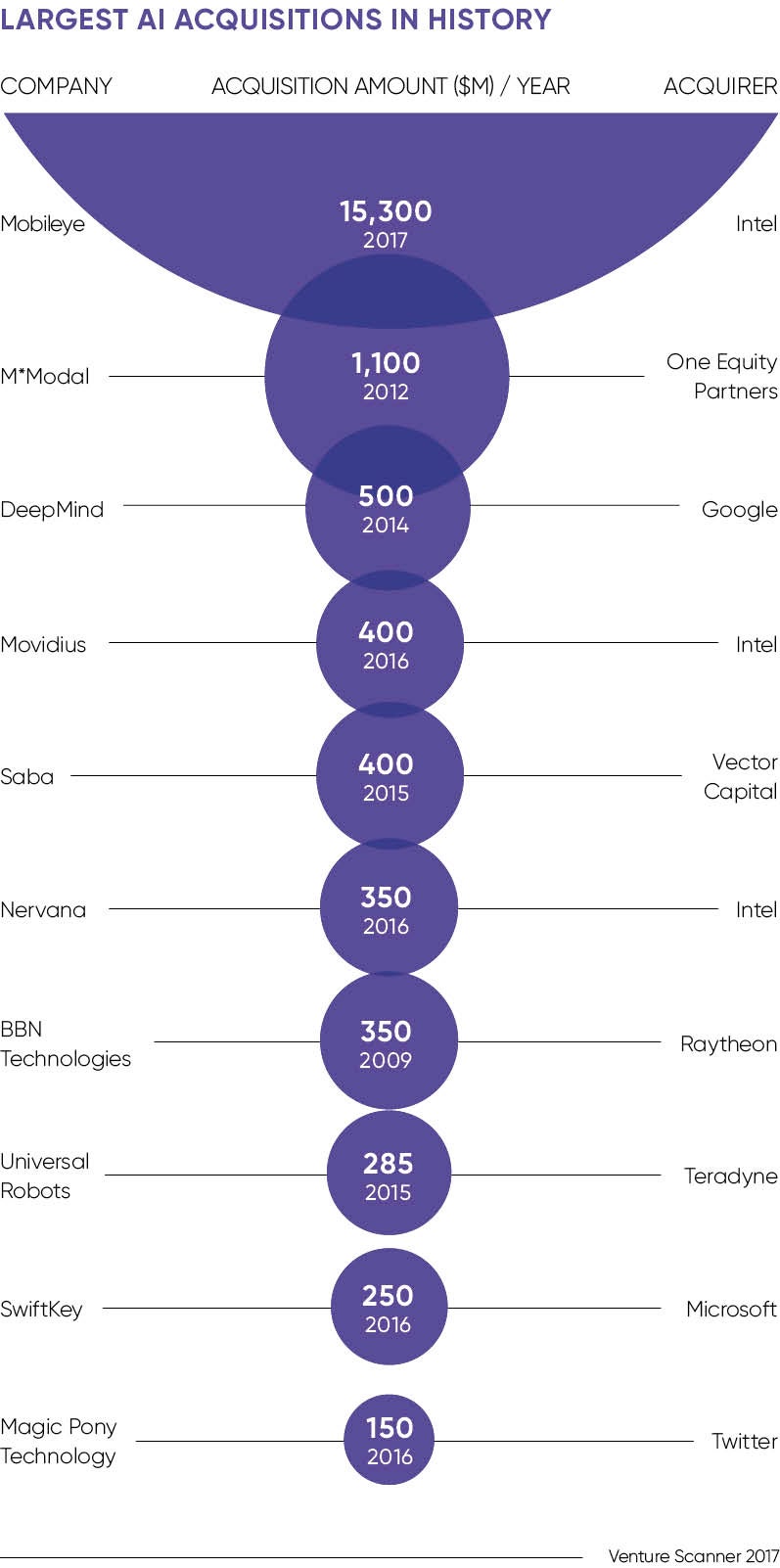

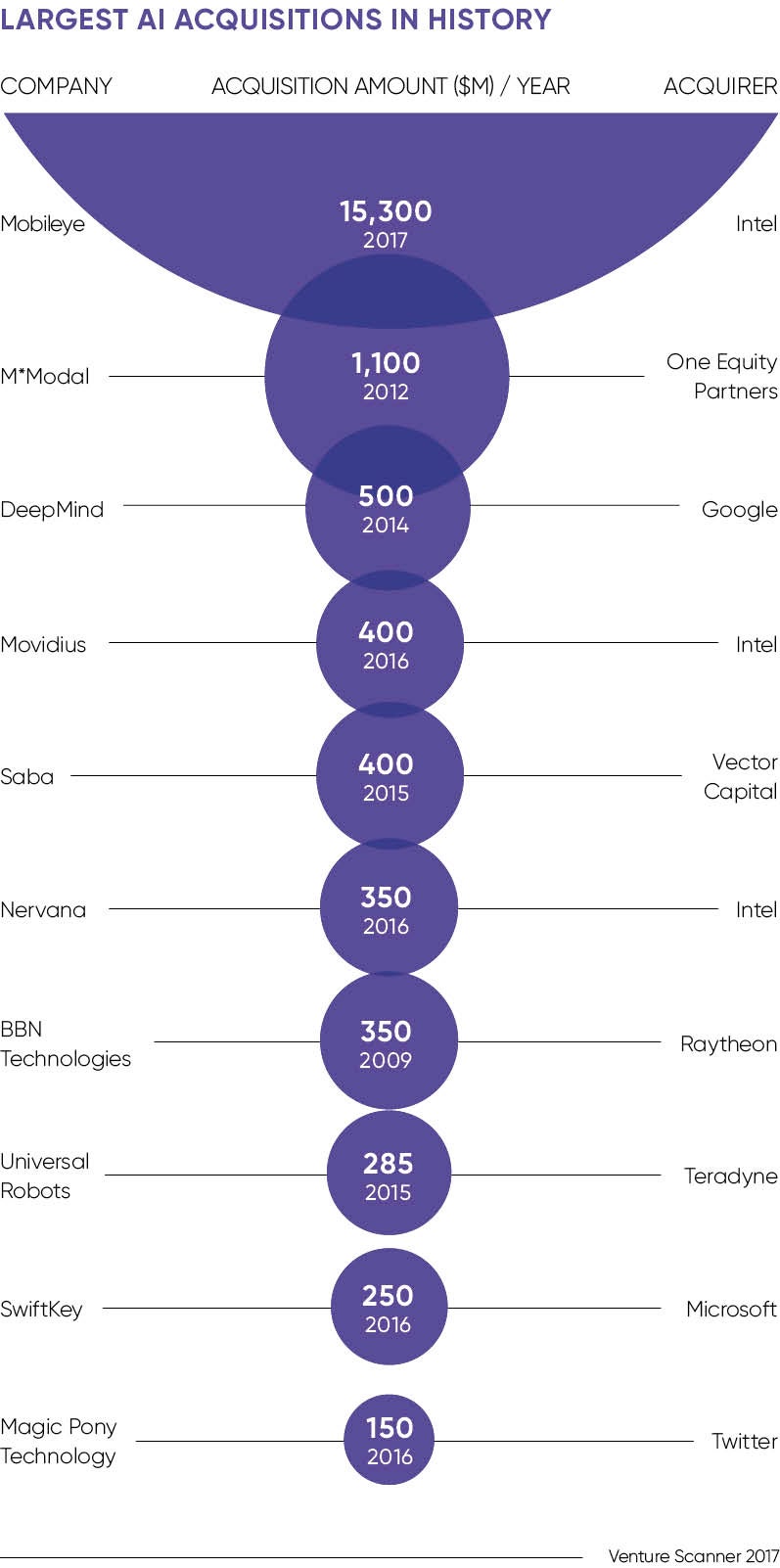

American chip maker Nvidia, for example, has seen its stock price treble in the past year after its graphics processing units became the chip of choice for companies training AI systems. This urged rival Intel to spend $15.3 billion acquiring Mobileye, a chip maker for cars and trucks.

“Several years ago, Nvidia committed itself as a company to investing in deep-learning,” says Jaap Zuiderveld, who leads Nvidia in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “Now that commitment is bearing fruit and we find ourselves in a position of leadership as this new computing model takes the world by storm.”

Intel isn’t the only company that is targeting a piece of the AI gold through mergers and acquisitions. The past five years have been defined by a flurry of acquisitions by large tech companies looking to expand their AI product portfolio and gain the expertise of niche startups. Google’s 2014 acquisition of London-based DeepMind was one of the largest at an estimated $500 million.

With the startups often snapped up before they can scale, these aggressive acquisition strategies have resulted in an industry divided between tech giants building AI services with the cloud infrastructure and vast data they own, and niche players applying AI to specific verticals or industry problems.

Data dominance

Ownership of data is critical because, try as they might, large tech firms can’t acquire all of the world’s AI talent, but they can own the data needed to train the AI with. This has resulted in a big six of tech firms primed to lead AI due to the data-intensive nature of their core businesses – Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, IBM and Apple.

Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Apple, for example, have been able to utilise the data they’ve gathered from their other businesses to take an early lead in the market for intelligent personal assistants. Facebook has used machine-learning to develop a messenger chatbot, while IBM has been an early-mover in the cognitive computing market with Watson. All six have willingly opened up their AI technology so any developer can build on their cloud infrastructure because they know data is the real differentiator.

“If AI is to truly resemble human consciousness, the stuff of films, in our lifetime, it will probably come from one of those companies as they’re the only ones with the data to train a model of that complexity,” says Brandon Purcell, senior analyst at Forrester. “AI will precipitate a new data gold rush, marked by data-motivated acquisitions. Companies that acquire data assets around a specific use-case will win. The resulting barrier to entry will be insurmountable.”

This ability to lead in certain use-cases means traditionally non-tech companies have the opportunity to grab a slice of their segment. Engineering giants GE, Siemens and Boeing are investing in factory automation while the likes of Ford, Toyota and BMW are battling with Google, Apple and Tesla in the car industry.

Meanwhile, there is a view that AI startups and companies in other industries can benefit from the democratisation of AI through the big six’s open source tools, such as Google’s TensorFlow and Microsoft’s CNTL.

The past five years have been defined by a flurry of acquisitions by large tech companies looking to expand their AI product portfolio and gain the expertise of niche startups

Many think this democratisation is vital to ensuring AI can address the widest reach of business and societal problems, and that confining innovation to a small pool of companies will give them too much control and harm AI’s potential.

“This is worrying because even Google’s huge reservoir of data has blind spots,” says Mr Purcell. “If the Googles and Amazons of the world control AI, the resulting systems will inherently be biased – even if they have the best intentions.”

Stephan Gillich, Europe, Middle East and Africa director for high-performance computing and AI at Intel, adds: “The more people involved in the AI conversation, the more industries will be able to benefit, and the sooner we will see the impact across government, business and society.”

However, others think the opportunity to democratise AI is already gone. Distributing innovation extensively beyond the big six is unrealistic due to a worldwide lack of programming talent and the hefty costs of acquiring it.

“Even with free platforms available, you still need highly trained, experienced and specialised data scientists to build good solutions that provide real value to end-users,” says Michael Feindt, founder of AI startup Blue Yonder.

When more AI programming skills are eventually introduced to the market, the big six needn’t worry. By open-sourcing their AI technology, they’ve already told the world that software isn’t a source of advantage to them – data is.

Despite AI sitting in people’s homes and driving big business investments today, the most powerful applications are yet to be seen. When they do emerge, the big six have laid the foundations to benefit most, but they still have each other to compete with. Meanwhile, the market will be more than large enough for enterprises and startups to carve out a lead in specific use-cases.

AI today

The AI market