Come rain or shine, many of us expect undisturbed access to consistent and on-the-go mobile connectivity that keeps us perpetually entertained, informed and connected. As it’s rolled out across the UK, 5G coverage promises an even faster and more efficient experience. But not everywhere will feel the benefit of the technology right away.

Why are remote areas left behind?

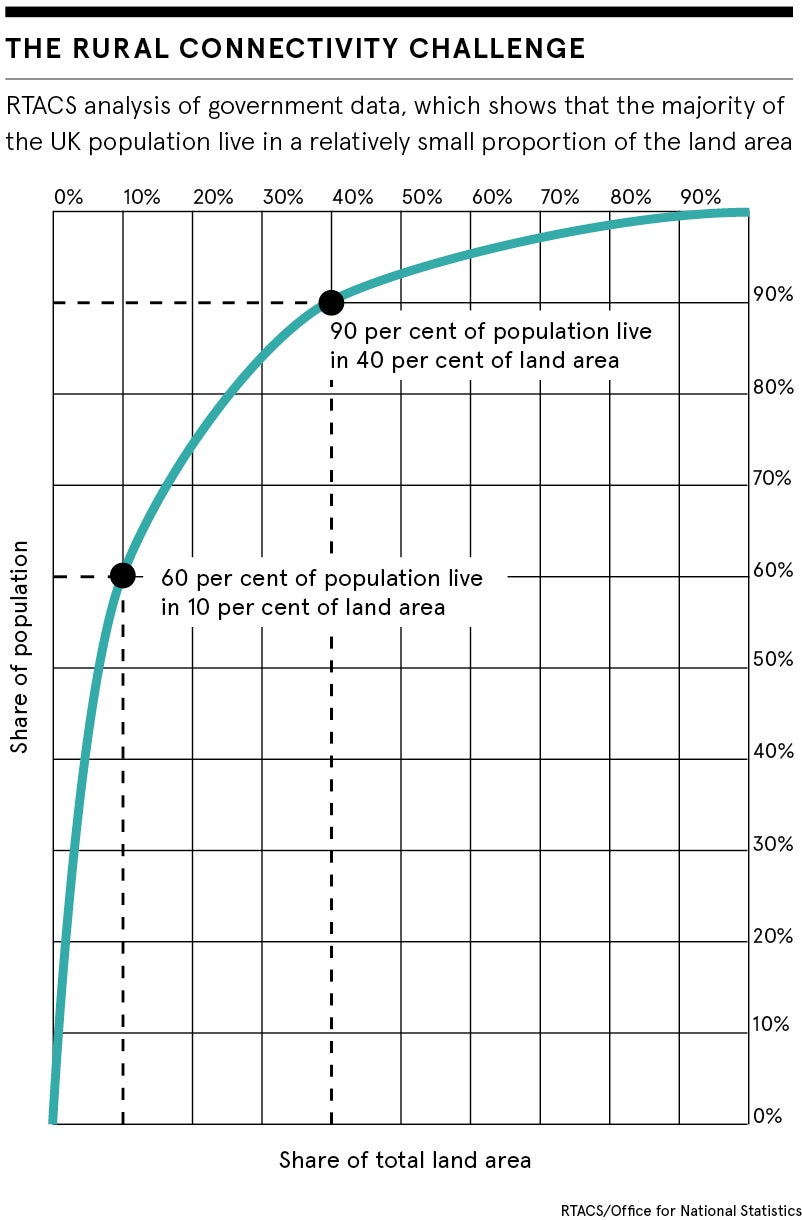

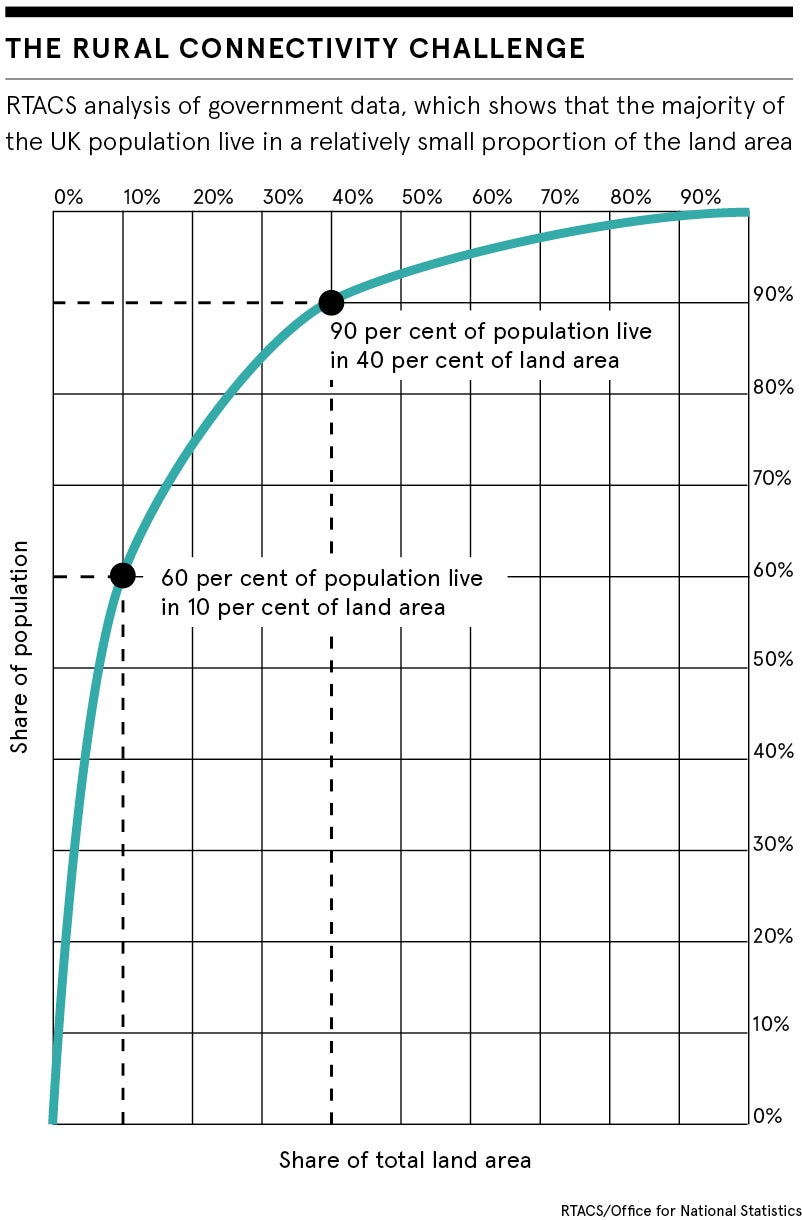

For years rural areas have experienced unreliable connectivity compared to their urban counterparts. According to UK communications regulator Ofcom’s latest figures, 9 per cent of the UK, predominantly located in rural areas, still have poor access to 4G.

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) identifies restrictions on antenna heights on masts, prioritising environment protections over infrastructure, higher costs for mobile network operators and lower return on investment due to lower population density, as key reasons for the urban-rural divide. It’s unsurprising then that as the UK 5G rollout makes headway, it’s cities and towns that are prioritised.

But there’s a strong case for rural 5G coverage. As the DCMS points out, much of the UK’s socio-economic activity is taking place online. And so, leaving rural areas behind could pose a threat to economic growth and social mobility.

Alternative solutions for rural 5G

Commercially, rural 5G coverage appears to be on the backburner. But, as evidenced by DCMS funding of several 5G trials in recent years, it seems to be an increasing priority for the government.

Cisco’s 5G RuralFirst project, for example, created testbeds for 5G across three remote sites. The project explored a number of 5G strategies, including 5G cloud core network, dynamic spectrum sharing, 5G radio access technology, agri-tech, broadcast and industrial internet of things.

The government also helped fund Quickline Communications’ trial of 5G technology across a range of rural applications, including smart agriculture, tourism and connecting poorly served communities, using shared spectrum in TV bands and a mix of local internet service providers.

Establishment of an ongoing 5G Rural Connected Communities Project demonstrates the DCMS’s aim to continue the advancement of 5G coverage in rural areas. In a bid to build the business case for investment in rural connectivity, it’s funding up to ten innovative use-cases.

Minister for digital and broadband Matt Warman says: “We are acting now to make the UK a world leader in 5G, and our visionary testbeds and trials show the technology and desire is there for it to have a huge, positive impact on Britain’s countryside communities. In the next wave of projects, the trials will focus on the value 5G will bring to the UK economy, how it can be used to tackle real social problems and how these applications can be commercialised.”

Will HAPS help with 5G coverage?

Last year, Ofcom made available airwaves, including a frequency band that supports 5G, which in the past were restricted. “We’ve opened up a conversation with mobile network operators (MNOs) that was once very difficult to have,” says Cristina Data, director of spectrum information and analysis at Ofcom. This is good news for rural areas where businesses and communities can apply to access airwaves, which are licensed to MNOs, but not currently used by them.

Although there are barriers to the technology becoming commercially viable, high-altitude pseudo satellites (HAPS) are also being presented as a possible alternative. It is hoped these satellites, deployed in the stratosphere at an altitude of 20km, will provide connectivity to remote areas, such as rural, coastal or mountainous regions.

“The ability to deploy HAPS over locations that are currently out of range of existing infrastructure will provide an alternative way of enabling 5G into rural areas quickly and without the need to build physical infrastructure which is proving overly expensive,” says Barry Ross, chief executive at e2E.

Satellites are another technology currently being trialled in the UK and are potential game-changers. Examples include OneWeb, which is seeking to launch a constellation of 650 satellites to deliver high-speed global connectivity. But there are challenges associated with the technology.

“Using satellites for telecoms still has technical and commercial challenges, in particular with regard to price, capacity and availability of services,” explains Warman. “However, the government has been actively involved in the work of European and international telecoms groups to study what technical and regulatory conditions are needed to develop the technology further.”

5G is not a one-size-fits-all solution

5G coverage may appear to be the silver bullet for rural Britain, but it’s not always the best solution.

“Connectivity comes in many forms and the requirements in rural areas differ a lot, so even though it’s now the buzzword, 5G is not always needed,” says Heli Frosterus, principal policy adviser, spectrum group, at Ofcom.

As some rural areas are still operating without 4G, there’s an argument to say that the next logical step would be to ensure those locations have access to it. To do this, the government has backed a shared rural network involving all the big MNOs. They are investing in a shared network of new and existing phone masts, which will bring 4G coverage to 95 per cent of the UK by 2025.

“Both technologies [4G and 5G] also have specific characteristics that suit different environments,” says Gareth Elliott, head of policy and communications, at Mobile UK. “5G, in its initial rollout, is about providing capacity while 4G is better at extending coverage. Capacity is less of an issue in rural areas, but as the technology improves and new innovations are brought to market, we see a strong role for 5G in rural areas in the future.”

Why are remote areas left behind?

Alternative solutions for rural 5G

Will HAPS help with 5G coverage?