Until recently, mention of drones would bring to mind either high-tech weapons being used in conflicts around the world or, at the other end of the spectrum, tiny quadcopter toys.

Until recently, mention of drones would bring to mind either high-tech weapons being used in conflicts around the world or, at the other end of the spectrum, tiny quadcopter toys.

But increasingly, drones are being put to work in a host of applications. While the drone deliveries promised by Amazon and others remain some way off, drones are improving health and safety at industrial plants and on facilities such as oil rigs by being used to inspect difficult-to-access and dangerous sites. They are being used by police to follow criminals and search for missing persons – Devon and Cornwall Police have just announced the country’s first 24-hour drone service.

The National Trust, which has banned visitors from flying drones on its properties, is using them to carry out building surveys without the need to erect scaffolding, which is expensive, time-consuming and off-putting to visitors. It is also using the machines to give visitors different views of its properties that were previously unavailable and is considering using them to create 3D models of some of its iconic structures to help visitors to understand them better.

Elsewhere, drones are being used to identify stressed crops and tackle diseases, to survey beaches for erosion and identify crop run-off that is causing water pollution. There are even plans for miniature drones to be used to pollinate plants in areas where bee and butterfly populations are struggling. It is not just in the air that drones are making a mark – there are suggestions that drone ships could carry freight around the world without the need for crew – or the space to house them.

“The benefits of these cool, little machines are just tremendous,” says Kurt Schwoppe, business development manager at Esri. “They provide a new window on the world that allows us to show things that have traditionally been missed by mapping organisations, engineers and government agencies.”

Booming business

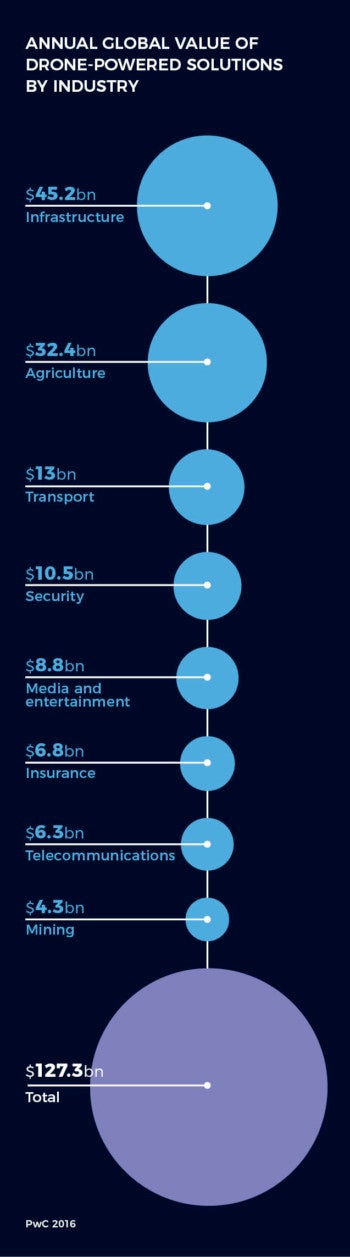

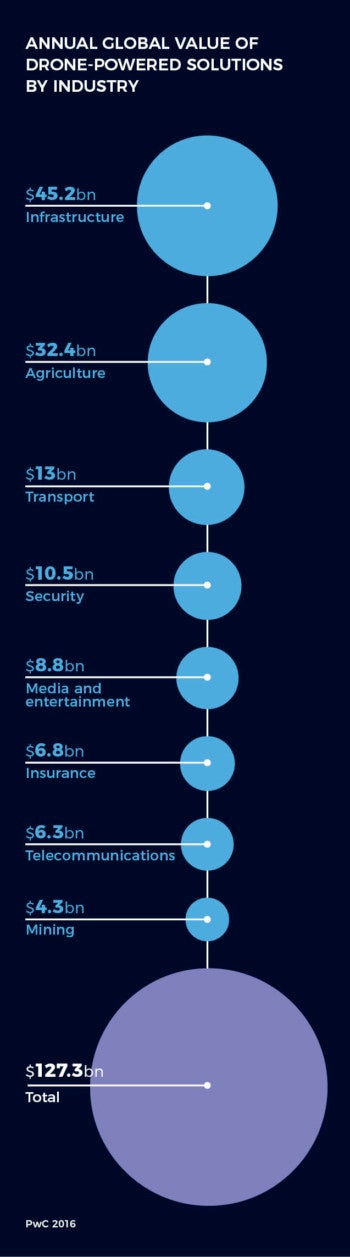

They are going to be big business too, with PwC predicting that the market will see explosive growth of more than 6,000% by 2020, up from about $2 billion in 2016 to $127 billion by the end of the decade.

The key to this boom is not going to be the drones themselves – the technology is fairly basic and has been well understood for decades. Some incremental advances such as better batteries and advanced, lightweight materials may improve their capabilities but not radically. What will really add value is the way they will interact with other technology.

There are even plans for miniature drones to be used to pollinate plants in areas where bee and butterfly populations are struggling

Identifying crop disease, for example, will come from using infrared cameras on drones that will be able to show diseased plants that look healthy to the naked eye. Meanwhile, the University of Buffalo has developed a method of using a swarm of drones to identify the extent of oil spills, in which each individual drone communicates with others in the group to ensure that they do not duplicate information and that they cover as large an area as possible.

The down side

However, like any technology, drones are only as good as the people who use them. Fears that they will be abused are typified by criminals using them to smuggle drugs into prisons and track police movements, and fears that terrorists could weaponise them. That’s why governments from Canada to China have brought in strict rules to control the use of drones, for example near airports.

China, the world’s biggest producer of the flying machines, has gone a step further, ruling that all drones must be traceable back to an individual owner, while police in Wuhan in Central China have recently taken delivery of drone-busting rifles that emit radio-jamming signals to knock drones out of the sky.

But Mr Schwoppe, for one, remains confident that the future is bright for drones. “We’re still at the tip of the iceberg,” he says. “These machines are empowering people. They will be a huge benefit for society, they really will.”