Sleeping on a friend’s sofa seems the most unlikely hotel concept ever to anyone over the age of 35. But the image so carefully, if questionably, nurtured by Airbnb, the short-stay rental business that in less than a decade has revolutionised the hospitality sector, has lessons the rest of the industry are fast embracing.

“By 2020, 50 per cent of travellers will be millennials [the demographic currently aged roughly between 18 and 35],” says Rob Payne, chief executive of Best Western GB, a membership organisation of more than 280 independent hotels. “They don’t want a one-size-fits-all hotel – they are looking for experiences and stories.”

Catering for the millennial

The rise and rise of the personalised experience is a key theme within the industry. Cloud 7 is a new company aiming to meet the needs of what they prefer to call “new travellers”.

“We don’t believe it’s just about age – Iris Apfel [the iconic American designer who turns 95 this year] was one of our inspirations,” says Cloud 7 chief executive Marloes Knippenberg. “This is to do with attitude and behaviour.”

Cloud 7 – so called because, after reading a survey that found 55 per cent of millennials would rather lose their sense of smell than their mobile, the founders dubbed the mobile phone the seventh sense – is opening hotels that use technology to create a sensation of spontaneity and local connections.

“No one wants an anonymous hotel room,” says Mr Doucet. “It’s all about a sense of place.”

So, instead of a lobby with a check-in desk there is a “social zone” coffee shop where a member of staff will come and register you via an iPad while you have a drink. In your room you can watch a movie from your own Netflix account, take a call in the shower via Bluetooth speakers and stream photos from your Android on to the TV.

Four Points by Sheraton is developing smart mirror technology in its hotel rooms

“Why should you have to pay for TV or only have TV in a language you don’t understand?” asks Antony Doucet, brand director of The House Hotel Collection. “This is not about technology to open and close the curtains, technology for technology’s sake. It’s simply about doing things as you would do them at home.”

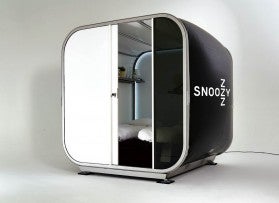

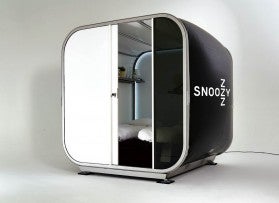

The use of technology has moved well beyond simply having wi-fi. Last year, Best Western showcased li-fi, a 5G system that transmits data using lights. “Wi-fi is now like a utility, like having power or water,” says John Hardy, founder of the Radical Innovation Awards, which promotes new ideas in hospitality. 2015’s winner was Zoku, an alternative hotel offering; runner up Snoozebox offers portable hotel rooms for events and festivals.

“But it’s very difficult for hospitality to keep up with the [technology] bandwidth required; people want to be able to connect anywhere and connect multiple devices. Add in to that personalised controls for lights, aircon, music – but not everyone wants to deal with all that,” says Mr Hardy.

Hence much of the technology is behind the scenes; it has to do with the cookies on your computer that allow hotels to recognise and remember customer preferences.

“Hoteliers seek to offer their guests the experience that fits their individual needs and personal preferences,” says Lee Horgan, chief executive at Newmarket, which provides technology to the hospitality industry.

“It is key that all the extra ‘little things’, such as optimum room temperature, bedding preferences or food allergy information, are taken into consideration. All these items help deliver the proper guest experience every time at the right time, which will be largely driven by data and sophisticated analytics.”

Big brands at the forefront of tech innovation

Mr Hardy believes it is the big publicly quoted companies that have driven much of the technology now found in luxury hotel rooms – all part of a bid to reduce margins by cutting back on staff numbers.

But an app that enables you to order new towels is hardly the point, says Mr Payne. “Hospitality is segmenting. What we are trying to do is create white space between all our brands,” he says. So the customers who want to stay in a Best Western Vib, featuring boutique style and technology, or Executive Residency may not overlap with those looking at the Plus or Premier brands.

Snoozy, the inflatable pop-up hotel room from Snoozebox, offers premium on-site accommodation at events and festivals

Best Western is not alone; Hilton has launched the Tru brand and Marriott a chain called Moxy – all aiming at millennials.

“Millennials attach a higher value to brands than the baby boomers do. They are looking to be surrounded by like-minded people and referrals are commonplace,” says Mr Payne.

[embed_related]

Instead of using a travel agent, millennials will use Instagram to find somewhere to rest their heads – or more likely, somewhere to party through the night with the locals. It is the experience that counts. Hence Cloud 7’s aim to offer not just information about the best places to eat or visit – after all, that’s a service that has long been available from really good front desks – but a kind of networking or friendship with locals.

The rise and rise of the personalised experience is a key theme within the industry

ZOKU

Japanese for family, tribe or clan, Zoku proclaims itself as the “end of the hotel room… a flexible home-office hybrid, with the services of a hotel and the social buzz of a thriving neighbourhood”. The Dutch company’s version of an hotel is almost more like an upmarket university campus. It offers live-work hybrids where “knowledge, ideas and people mingle”. The design takes elements from the Tiny House movement, lofting the bed and making the table the focus of the room. It’s all about finding a community.

UMAID BHAWAN PALACE

Located in Jodhpur, the Umaid Bhawan Palace took first place in TripAdvisor’s Traveller’s Choice 2016 rankings, with reviews calling it “a living dream”, “real touch of royal traditions” – the hotel is merely part of a royal palace in which the family still live – and “an architectural marvel”. By no means cheap, this is as experiential as it gets; if you want the experience of being an Indian maharaja, this is it. With 26 acres of gardens and opulent Art Deco styling, it is proof there’s nothing new in experiential design.

ALBERGHI DIFFUSI

More of a movement than an hotel, Alberghi Diffusi is a means of reviving small Italian villages off the beaten track. An almost untranslatable concept – literally, “spread out hotel” – it offers rooms dotted throughout a village, but with a central reception and dinner in a local restaurant. It could be a conical trulli down in Puglia or a villa near the Austrian border, but these privately owned spaces offer a glimpse into a community and provide a purpose for historic buildings that might otherwise fall into ruins.

Catering for the millennial

Big brands at the forefront of tech innovation