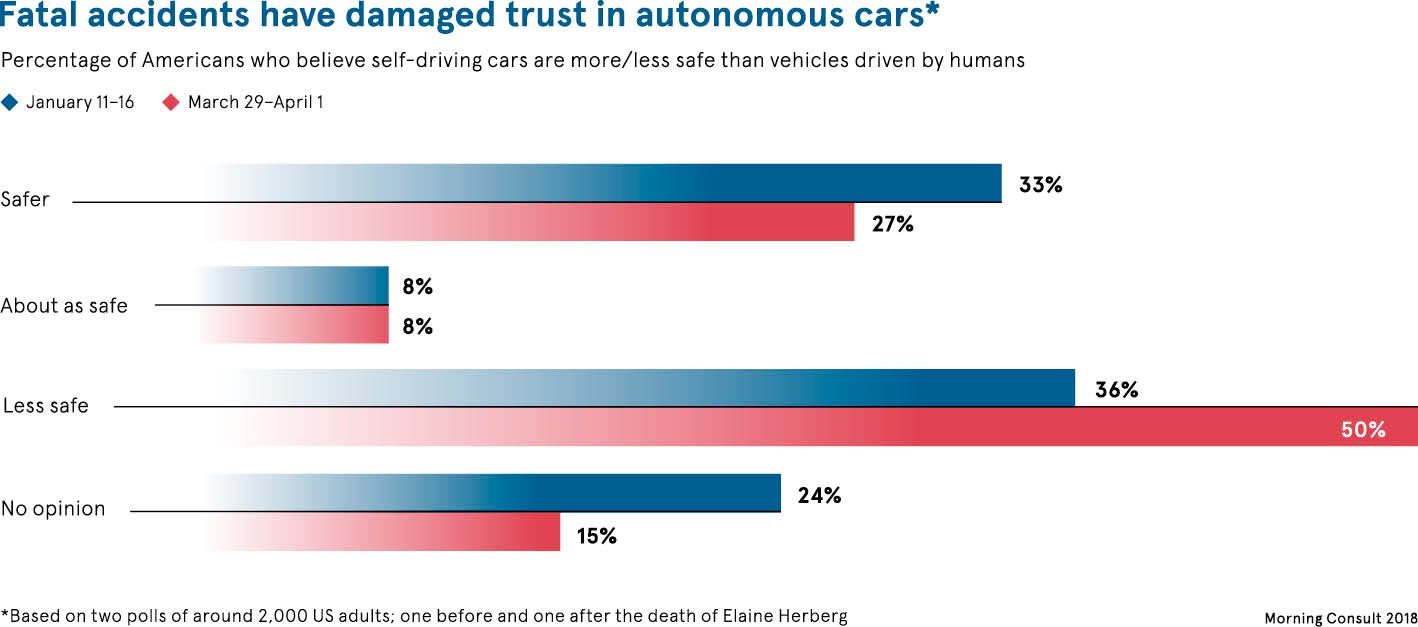

Elaine Herzberg’s death, earlier this year, will go down in history as the first fatality attributed to a self-driving car. It will not be the last. At around 10pm on March 18, the 49 year old wheeled her bicycle across a dimly lit road in Tempe, Arizona, and was struck by Uber’s modified Volvo XC90 SUV, a prototype self-driving car powered by artificial intelligence (AI), travelling at 40mph.

Ms Herzberg’s tragic demise triggered a widespread debate on the safety of fully autonomous vehicles, despite the fact that this AI-fuelled technology promises to save millions of lives around the world.

Uber was forced to suspend testing. Its crash report, published in early May, centred on a fault that decides how the car should react to objects in its path. Although the vehicle’s sensors detected Ms Herzberg, the software was tuned too far in favour of ignoring objects that could be classed as “false positives”, like plastic bags or other litter. The report also stated that the human safety driver was not paying close enough attention to intervene.

AI not prey to the same factors which causes road casualties

Consider that officially self-driving cars have been on roads since 2009, albeit in restricted conditions, and this is the first death. The latest National Safety Council statistics reveal that, on average, 110 people suffer non-autonomous traffic-related fatalities in America every day. Indeed, there were 40,100 such deaths last year and 6,000 of them were pedestrians. By allowing Artificial Intelligence, which can’t be drunk, distracted, tired or influenced by road rage and other emotions, to take the wheel, those figures could, in theory, be significantly dented.

“Human drivers are committing a holocaust, killing 1.2 million people every year on roads around the world and maiming another 50 million or so,” says Calum Chace, author of The Economic Singularity. “Road accidents are the most common form of death for people aged between 15 and 29. The sooner we can stop this carnage the better.”

The Uber incident serves to highlight the disparity between the current levels of expectation for AI and the reality of its relative maturity. For business leaders, education is essential to narrow that gap.

C-Suites excited by the potential of AI but reluctant to commit to it fully

Mind-boggling AI figures abound. Global business value derived from Artificial Intelligence is projected to reach $1.2 trillion by the end of the year, representing a 70 per cent increase from 2017, according to industry analysts Gartner. It is forecast to hit $3.9 trillion in 2022, with the three central sources of AI business value being customer experience, new revenue and cost-reduction.

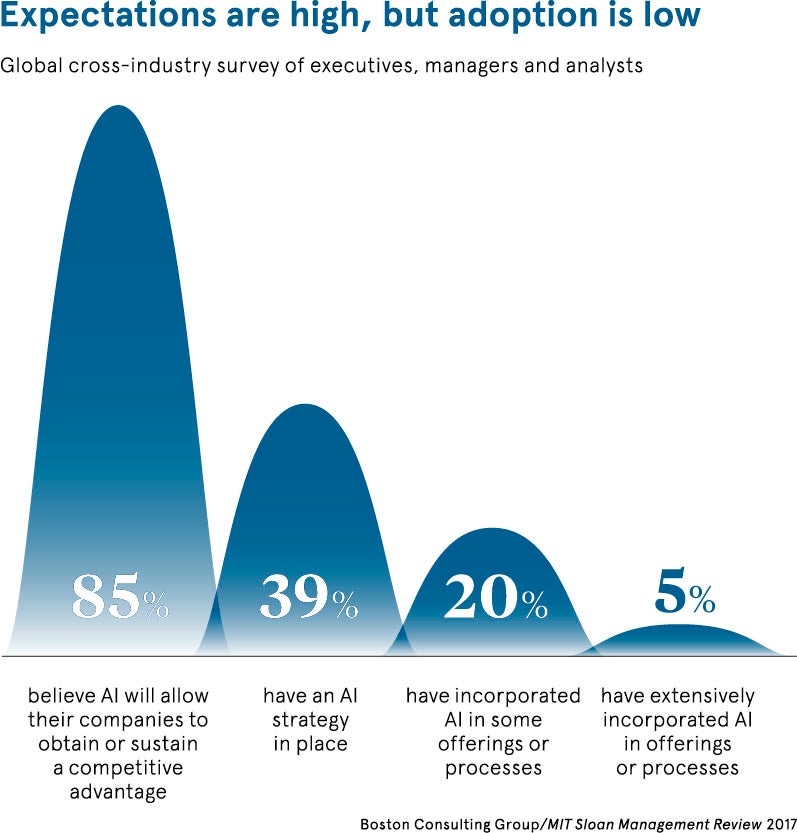

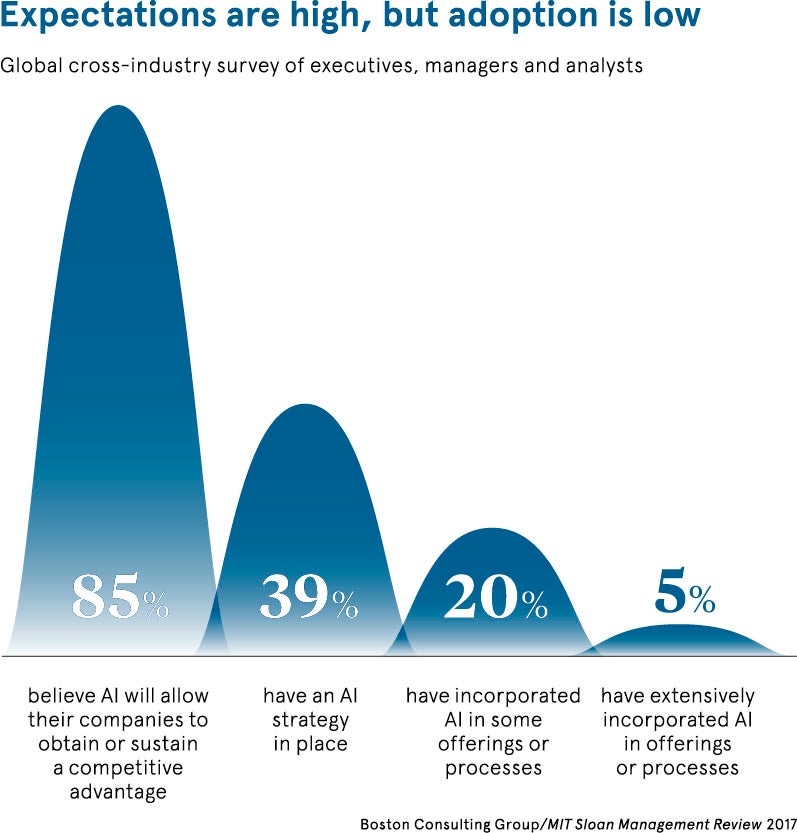

Further, a Boston Consulting Group and MIT Sloan Management Review study suggests three quarters of C-level executives believe AI will enable their organisations to pivot into a new business. Additionally, almost 85 per cent think AI will allow their organisations to gain a competitive advantage. However, only 5 per cent have so far extensively incorporated AI into its processes.

We risk discarding AI before it has had a chance to develop if we fail to recognise that certain traits we would associate with intelligence haven’t been achieved yet

As with self-driving cars, it appears C-suiters are excited by the potential of Artificial Intelligence, but there is uneasiness about putting the pedal to the floor and committing fully. The chasm between ambition and execution is significant and growing. Why?

“AI has been a mainstay in science fiction since its inception,” says Ray Eitel-Porter, Accenture Applied Intelligence lead in the UK and Ireland. “And there’s a reason it does so well at the box office: we’re addicted to fantasies about super-intelligent robots. Despite AI progressively entering the real world, it’s hard to shake the image we’ve built up in our imagination.

Successful artificial intelligence requires experimentation and high-quality data

“Google’s AlphaGo and progress in image recognition show that Artificial Intelligence has indeed surpassed humans in some areas. The gap between expectation and reality widens when it is put to the test in the real-world. It’s our own adaptability and common sense which make us so unique, and we often forget this. One of the best examples is autonomous vehicles, which can be duped by scenarios that would be easily understandable for a human.

“We risk discarding AI before it has had a chance to develop if we fail to recognise that certain traits we would associate with intelligence haven’t been achieved yet. We’re still in the early stages of a fast-moving field with limitless potential. Leaders should avoid locking themselves into contracts with one provider, maintaining the flexibility to take advantage across the vast ecosystems which will develop over the coming years.”

Peter Bebbington, chief technology officer of Brainpool, a worldwide network of AI and machine-learning luminaries, agrees. “There’s a preconception that AI is this perfect solution,” he warns. “Business is uncertain, life is uncertain and nothing can give perfect prediction. Only charlatans promise perfection. AI requires a level of experimentation to find the right business model, but experimentation isn’t always a term that sits comfortably in business or with the public.”

Emphasising the importance of accessible and clearly presented data, Dr Bebbington says: “Businesses can tend to believe that you plug in an AI solution and watch it go. But algorithms need to learn before they can give any high degree of accuracy. Algorithms on their own are stupid, they need pointing in the right direction with the correct data classification, otherwise it’s a case of garbage in, garbage out.”

Business leaders must be educated on both AI and data

Educating business leaders about both AI and data is imperative, urges John Ridpath, head of product at Decoded, a global organisation that aims to demystify emerging technologies. “There is a lot about AI in pop culture and because of that people think of it as some kind of awesome force, but in truth we’re on a continuum of technological change,” he says. “It’s not like everything will change as soon as we switch on the AI computer.

“A lot of our clients want to understand Artificial Intelligence, which has reached such a level of hype that it is hard to deconstruct. There has been excitement and fear about AI since the 1950s, when Alan Turing [mathematician and founder of computer science] was alive. Buying straight into the technology is not enough. You can’t just bring an AI expert or product into your business and expect it magically to start doing anything useful. A big part of this is ensuring workers have access to the right tools and knowledge.”

Mr Ridpath lauds Airbnb as a pioneer in this area. Last year 700 – around 10 per cent – of its employees graduated from the in-house Data Academy. That understanding for tech is paramount, now and in the future. “If you want to do something deep and meaningful with your data that will offer a competitive advantage, it requires internal capabilities and skills,” he says.

In 30 years, a robot will likely be on the cover of Time magazine as the best CEO

While Jack Ma, Chinese business magnate, and co-founder and executive chairman of Alibaba Group, says provocatively: “In 30 years, a robot will likely be on the cover of Time magazine as the best CEO.” He adds: “Robots should do only what humans cannot.” His message is clear that blindly ceding all control to technology is fatal.

“The organisations seeing the greatest benefits from AI today are the ones deploying it alongside people, creating business processes powered by AI, yet with enough checks and balances through the right level of human intervention,” echoes Senthilkumar Ravindran, executive vice principal and global head of Virtusa’s xLabs.

In the Uber case, had the human safety driver been paying better attention perhaps Ms Herzberg’s death could have been avoided. While it will take more time to test and deploy AI, its potential is immense. Early adopters stand to benefit the most, though they must know when to apply the brakes.

AI not prey to the same factors which causes road casualties