At the beginning of the 1900s, the useful electrical devices that predate today’s smart home began gaining popularity. Proliferation of the electric typewriter, which was invented some 30 years earlier, for example, and the powered sewing machine set a trend in motion.

Fun and information were also to be had, and in the ensuing two decades, phonographs and home radios became popular.

From the 1930s, home living was more machine led and ovens that could control temperature were being bought in the mainstream, while electric toasters and kettles also saved time. Meanwhile, vacuum cleaners, many of which were “Hoovers”, became essential.

The development of computers in the 1940s, spurred on by wartime military code-cracking, eventually made the home more sophisticated. Two decades later, the first home automation processing device, Echo IV, was designed. The machine, a private venture by a Westinghouse engineer, was designed to control home temperature and turn on appliances.

By the 1980s, programming tasks was a more widely available feature and became hugely popular. The digital thermostat, to set heating, was commonplace, as were the programmable washer-dryer and dishwasher.

The booming popularity of the microwave slashed typical cooking times from thirty minutes to five, prompting convenience dinners. VHS and Betamax video recorders that could be preset meant people no longer had to miss their favourite TV shows and could now watch them anytime.

The American Association of House Builders coined the term “smart house” in 1984 and, during the next decade, movies attempted to depict it. Technology to help safeguard elderly people living alone was also becoming well used.

Home computing had begun to reach the masses, with the BBC computer and the IBM PC both launching in 1981, the early Apple Macintosh in 1984 and the Microsoft Windows operating system a year later. Fast change ensued, and technology miniaturised. It took until the late-1990s for small mobile phones to become commonplace, and by the 2000s smartphones and portable MP3 players, such as the iPod, sold in large numbers.

The arrival of such sophisticated computing technology and home broadband to connect it quickly, met with the continued desire for easier home life. Nest, the business behind mobile phone controlled heating, was established in 2010 and bought four years later by Google for an astonishing $3.2 billion. Meanwhile, smart meters from a variety of firms allowed homeowners to check their energy consumption.

And so there was the beginning of the home-based internet of things, in which web-connected objects could communicate with each other and with the homeowner in order to regulate settings.

[embed_related]

Other devices began to emerge, such as smart security which would only allow access to designated people and would notify parents of children arriving back home after school. Equally, smart fridges, air conditioning, washing machines, curtains and blinds, lighting and televisions allowed homeowners to change settings or programme actions remotely.

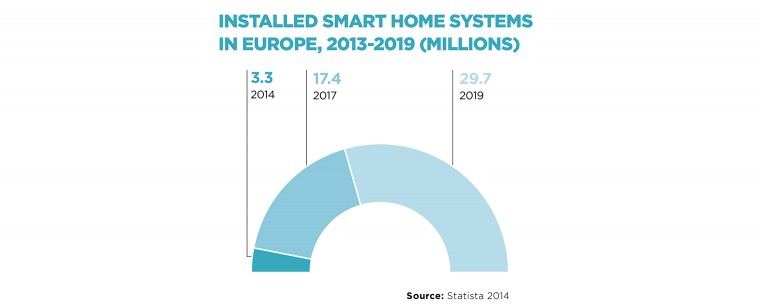

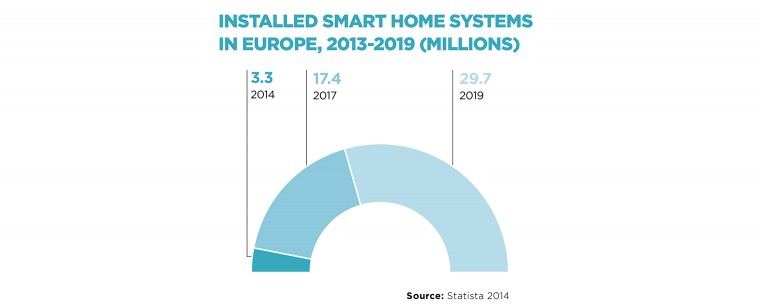

By 2013, smart devices were a key feature of the annual Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. According to BI Intelligence, almost two billion smart-home, connected devices are now thought to be installed, with nine billion expected to be in place by 2018.

People can water plants remotely and vary temperatures between rooms, while setting the kettle to boil at a certain time for their arrival, and automatically streaming their favourite music to the room they walk into

Latest developments allow people, when in the supermarket, for example, to check on their phone what is stocked in their smart fridge. Ovens adjust temperature to suit programmable recipes. Baby monitors are increasingly accessible remotely for parents, while home furniture will have more controls.

People can water plants remotely and vary temperatures between rooms, while setting the kettle to boil at a certain time for their arrival, and automatically streaming their favourite music to the room they walk into.

System standards, however, are far from finalised with companies, such as Google, Samsung and Apple, battling the specialists and looking at how they can connect their own systems to other home devices. Efforts are apace to solve the standards issues, including the Linux Foundation’s AllSeen Alliance, backed by 23 appliance and technology firms.

The pace of adoption of the smart home will be affected by consumers’ perception of ease of use, compatibility, cost and privacy. Whatever the rate of take-up, with people’s desire for an easy life and manufacturers’ high levels of investment, proliferation of smart homes is inevitable.