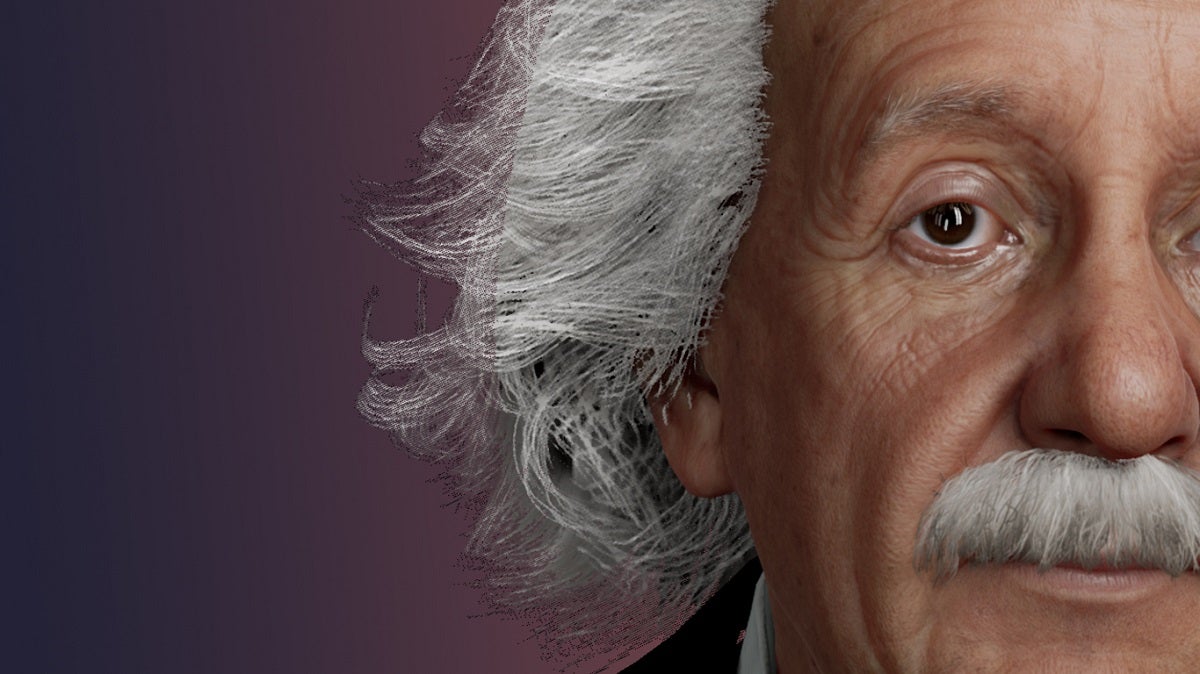

He’s the ultimate science teacher. History’s most brilliant physicist brought back to life, promising to unlock the mysteries of his subject. He’s approachable too, with twinkly eyes and a mischievous Teutonic lilt.

This is Digital Einstein, a chatbot that recreates the great man’s face and voice. The AI-powered virtual Albert can set quizzes, answer questions and even offer opinions – just ask him if he thinks the Earth is flat.

This is the product of an international collaboration involving teams in Europe, the US and New Zealand. The voice element has been provided by Aflorithmic, a Barcelona-based company whose COO, Matthias Lehmann, sees education as a key use case.

“By using these chatbots in schools, you could bring subjects to life for kids,” he says. “Wouldn’t it be great to learn from these amazing figures?”

But beneath the glitzy visual rendering and the pattern-recognition software that produces Digital Einstein’s tailored responses, there are questions. Are these chatbots appropriate for education, with its emphasis on fairness and mutual development? Just because we can bring these titans back from the past, is it right to entrust them with our children’s future?

Education is a social activity that’s about personal development. It’s not just knowledge transfer

Until now, such questions would have been academic. Chatbots were always too unsophisticated to have any useful role in education. Unless the conversation stuck to a planned flowchart, they would get confused.

But other forms of AI have been infiltrating our schools. Intelligent learning programmes, which give each user a personal education plan tailored to their existing knowledge, are already helping thousands of students. Using games and quizzes, these programmes offer tips on how to develop at a suitable pace and recommend which modules to study next.

Mark Raymont, a maths teacher at All Saints Church of England Academy in Plymouth, is an early adopter and fan of such assistance. Having implemented Sparx, an AI-based system that provides bespoke homework plans, he reports that his classes’ overall homework completion rates have improved to more than 95%.

“Instead of increasing homework, it has actually streamlined it,” says Raymont, who adds that the technology has provided further benefits in the classroom. “We use Sparx to identify trends. Our system gives us more in-depth insights into how a class, or an individual student, is doing. It enables us to provide more support to disadvantaged learners. Parents have been very positive.”

Eureka moment

The recent sharp increase in chatbot capability has resulted from advances in natural language processing (NLP) technology and contextual AI. These have given the bots more emotional intelligence and enables them to go off script and have back-and-forths with users. Instead of simply mapping out a student’s learning pathway, they can be used as virtual teaching assistants.

Take-up has largely been limited to a few universities, which have built their own Einstein-style systems. But there are signs that the technology is trickling down.

The tech team at Bolton College, a provider of further education and vocational training, has created Ada, named after the 19th-century computing pioneer Ada Lovelace. The chatbot is equipped with IBM Watson’s NLP platform and dozens of question-and-answer pairs, crowdsourced from teachers. It can field subject queries via Android, iOS and Alexa, and provide near-instant responses.

The project is still in its infancy, but Aftab Hussain, the college’s learning technology manager, reports that his team is already speaking to other organisations with a view to sharing the technology. He believes that virtual teaching assistants will become a common feature throughout the education system.

“Every student and teacher will have one in years to come,” Hussain enthuses. “When students from other schools have come here, they’ve said: ‘Why haven’t we got one?’ My ambition is that every child, from the age of three upwards, has a personal digital companion to support their studies.”

The limits of genius

For all the chatbot champions’ optimism, constraints remain. Processing power is a big one – Digital Einstein can still only speak to a handful of people at a time, for instance, and answer about 300 questions.

The ultimate goal, for both Digital Einstein and Ada, is to have meaningful responses to a vast number of potential questions. But, even then, it remains to be seen whether chatbots can branch out beyond factual answers into subjects that require nuanced discussion.

Wayne Holmes, a consultant on AI and education at Unesco, is sceptical about that prospect. “So far, they can work only in specific domains, such as mathematics, where there’s a right answer,” he says. “In subjects such as English, they are less effective. I don’t believe that any student will ever be able to have an in-depth conversation with a chatbot.”

Holmes issues a further caveat – a particularly salient one, given that recent research has found that up to 80% of children in the UK lack sufficient communication skills when they start school.

Our system gives us more in-depth insights into how a class, or an individual student, is doing. It enables us to provide more support to disadvantaged learners

“These systems separate children from their peers and the teacher,” he says. “They claim they can do the job better than the teacher, but they have a limited understanding of what education is about. Education is a social activity that’s about personal development. It’s not just knowledge transfer.”

Perhaps the biggest issue with virtual learning assistants is a socioeconomic problem. Even before Covid-19, the gap between rich and poor students in the UK was among the widest of any developed nation. This has only widened during the lockdowns. According to the National Foundation for Educational Research, students with disadvantaged backgrounds fell further behind in 2020, losing far more learning time than their more affluent counterparts. With this problem in mind, many educators will feel that it would be unwise to introduce more teaching tech for use on expensive devices such as laptops, tablets and smartphones.

As with many dilemmas about digital adoption, there is probably a middle ground to be found for virtual teaching assistants. By using these in the appropriate situations, promoting social equality and preserving teacher-pupil relationships, education providers can bring the best out of a hugely promising technology.

But how exactly will they achieve that? For now, at least, it’s a question that even Einstein might struggle to answer.

He’s the ultimate science teacher. History’s most brilliant physicist brought back to life, promising to unlock the mysteries of his subject. He’s approachable too, with twinkly eyes and a mischievous Teutonic lilt.

This is Digital Einstein, a chatbot that recreates the great man’s face and voice. The AI-powered virtual Albert can set quizzes, answer questions and even offer opinions – just ask him if he thinks the Earth is flat.

This is the product of an international collaboration involving teams in Europe, the US and New Zealand. The voice element has been provided by Aflorithmic, a Barcelona-based company whose COO, Matthias Lehmann, sees education as a key use case.