Integration of internet of things and big data analysis promises to transform urban life. The technologies behind smart cities can simplify the delivery of government services, minimise traffic congestion and reduce energy consumption.

And all these activities can be carried out in such a low-key manner that it’s easy to miss the fact that they’re going on at all; much less that they are using our personal data to do it.

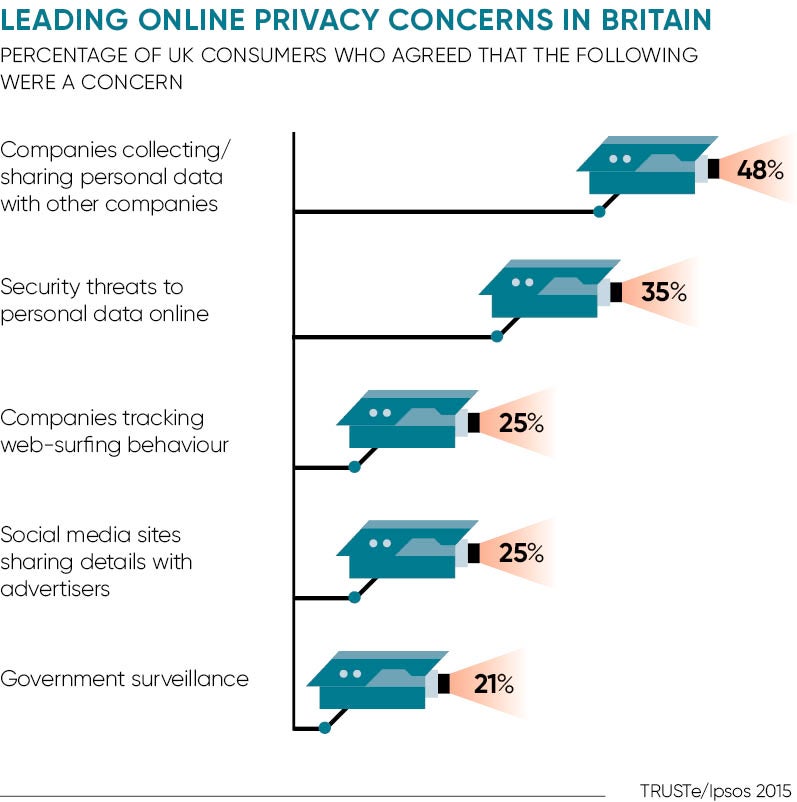

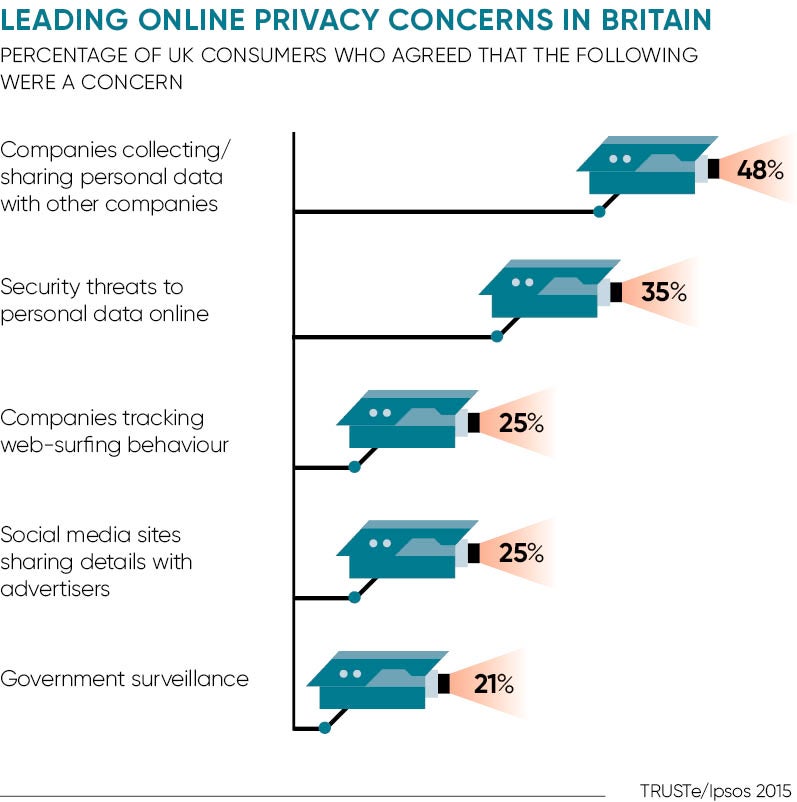

However, citizens are waking up to what all this monitoring involves. In a recent survey from Broadband Genie, for example, almost seven in ten respondents said they were worried about the privacy implications of having their personal data collected and retained.

“There is an inherent risk of mission creep from smart cities programmes to surveillance,” says Adam Schwartz, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “For example, cameras installed for the benevolent purpose of traffic management might later be used to track individuals as they attend a protest, visit a doctor or go to church.”

Concerns like these have hampered planners looking to reap the full benefits from smart cities, usually quite rightly.

But what could be done if privacy simply wasn’t an issue?

It turns out, quite a lot. “Crowd behaviour is particularly interesting in the smart-city space. Fitbit and trackers that are readily available to consumers can monitor anything from steps taken to vital signs,” says Collette Johnson, head of medical at technology consultancy Plextek.

“If the data from these devices was left ‘open’, this behaviour can be easily tracked and help inform anything from investigations into crowd safety problems to unusual behaviour tracked from connected, open consumer devices.”

There is an inherent risk of mission creep from smart cities programmes to surveillance

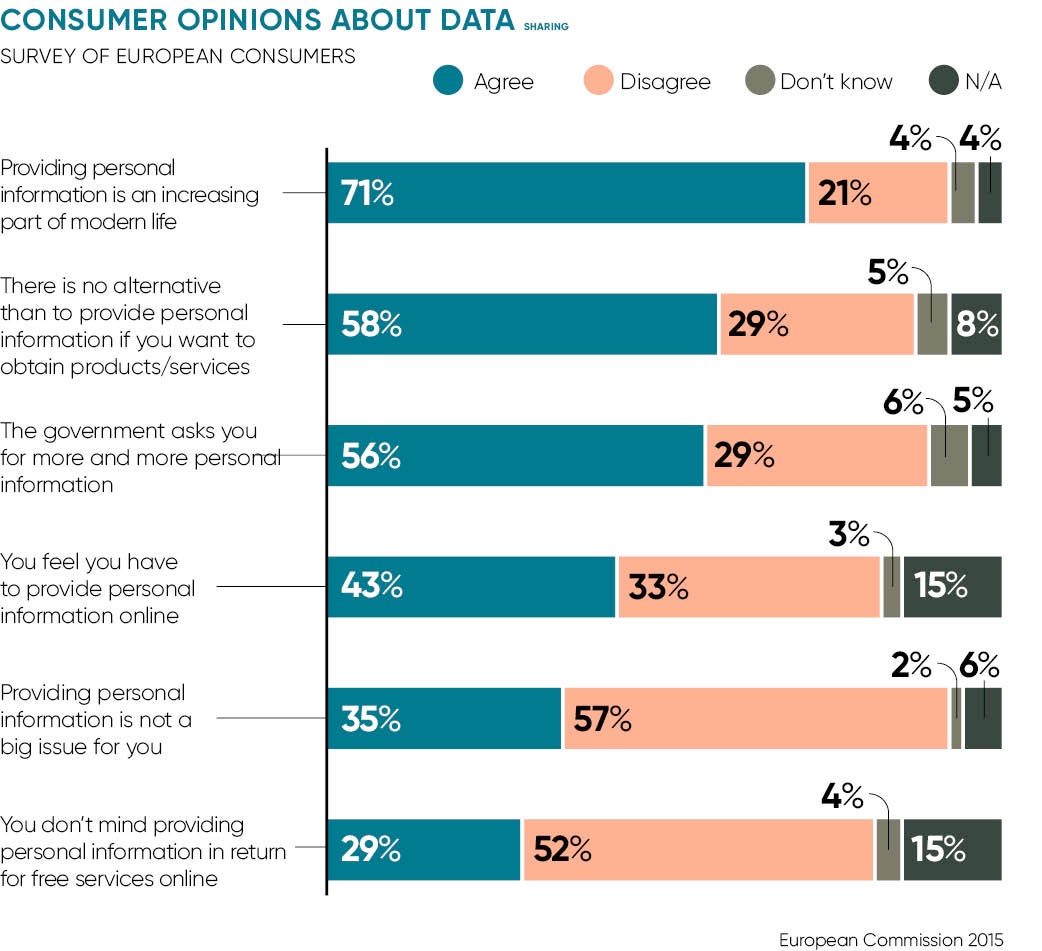

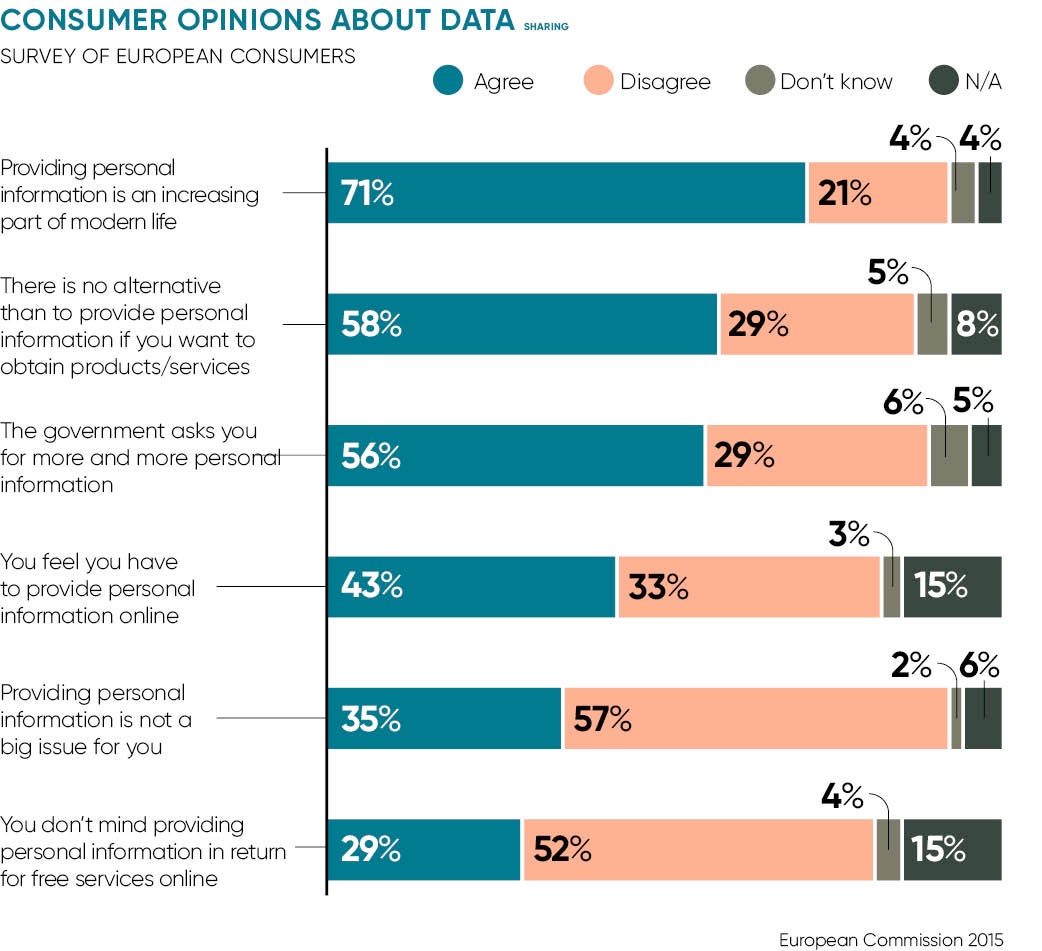

In many areas of life, people are happy to sign away their personal data, Facebook being an obvious example. And the same sometimes applies to smart city applications, depending on the data that’s being gathered and what they’re getting in return.

“For example, if it’s cars driving along a street, people don’t care, but when it’s a person, it’s different,” says Bill McGloin, chief technologist at Computacenter. “We’ve done a few where one of the benefits is that people get free wi-fi and they’re very, very happy, but they aren’t necessarily thinking about their privacy.”

Depersonalising data can help make sure that individuals can’t be identified, but this makes the information less useful.

“Techniques such as such as aggregation and anonymisation pose a challenge from a smart cities point of view, in which data sharing is crucial,” says Ben Calnan, who leads the smart cities sector at people movement consultancy Movement Strategies. “These processes reduce the power of the data and prevent datasets from being combined, as is required for a truly joined-up approach.”

The benefits

Where personal data is left identifiable, it’s remarkable what can be achieved, with China being the poster child for this sort of application. In some cities in Xinjiang Province, for example, drivers have been ordered to install satellite navigation equipment in their vehicles.

And more everyday applications are starting to emerge. “With Transport for London, for example, you have an Oyster card, but when you go to China now they’re using facial recognition,” says Mr McGloin. “They can accept that over there.”

Last year, the main railway station in Beijing started trialling facial recognition technology to verify the identity of travellers and check their tickets are valid for travel. In the city of Yinchuan, meanwhile, a passenger’s face is linked to their bank account, enabling bus passengers to pay automatically simply by having their faces scanned.

In the West, other emerging smart cities applications are also pushing the limits of personal privacy, most notably through Minority Report-style predictive policing.

This targets resources based on the location and timing of previously reported crimes, and sometimes on the type of people who have committed them. In the United States, where almost half of police forces are using predictive policing, some are even incorporating the Facebook profiles of known offenders in their systems.

In the UK, the systems trialled by several forces use only data on time, location and type of crime, although that’s not for lack of enthusiasm.

“We’re working with a couple of police forces that are looking at what would be possible in the future and I think the challenge is now that the technologies are evolving quicker than the legislation,” says Mr McGloin. “People will use technologies until they’re told they can’t, so we’re starting to see applications that infringe on people’s privacy.”

Public opinion is a funny thing, however. Sometimes, a lack of privacy causes outrage, but much of the time, people are happy to give away their personal data if it makes their life easier or more fun. It remains to be seen whether in years to come, privacy will be regarded as a quaint, old-fashioned idea that has passed its time.