The beauty landscape appears a healthy shade of green with UK sales of certified organic health and beauty products rising 21 per cent in 2015. The Soil Association figures also show a further 14 per cent increase in 2016, while Kline forecasts the global natural cosmetics market is set to be worth £34 billion by 2019.

The free-from message that dominated the last decade has been understood with a shift in consumer focus to what is really in products. Natural beauty choices are the next step for those conscious about the food they eat, with recognition that what we put into, as well as on our bodies, impacts our appearance and wellbeing.

The beauty wellness trend

The growth of the “clean” eating and wellness trend, and influencers like the Hemsley sisters, have given green choices a “cool” legitimacy. “It’s not just the mindset that’s resonating, food trends are also making the crossover into beauty,” says Jessica Smith, visual researcher at The Future Laboratory.

She cites brands with edible ingredients such as Evoleum, fresh-batch brands like Nuori, with formulations made every 12 weeks for maximum efficacy, and LOLI that allows consumers to play kitchen alchemist. Expect traceability from farm to dressing table.

“I am what I eat” now also pertains to “what I apply”. With social media sharing of beauty products, from scrubs to serums, these choices define identity and increasingly influence purchasing decisions.

“Green features are more salient in purchasing deliberations than low prices and strong brand names, with nearly six in ten buyers preferring natural ingredients, even if this impacts on price,” reveals Eileen Bevis, Euromonitor’s head of consumer lifestyles and survey.

Notably, green preferences rise among the consumers of the future. Mintel reports searches for natural or organic haircare increases from 34 per cent to 41 per cent in 16 to 24 year olds and from 53 per cent to 61 per cent for facial skincare.

Consumers read ingredients or notice if packaging is not recyclable and they will call brands out on it

“Awareness has increased exponentially thanks to the internet and transparency is now the norm,” says Marcia Kilgore, creative adviser for Soaper Duper. “With the mass of information shared, it’s difficult not to feel the responsibility for a product that you’re buying.”

Yet consumers feel brands often fall short. Mintel data reveals 78 per cent of people surveyed think companies (not limited to beauty) should act ethically. However, 73 per cent find it hard to tell how ethical a brand really is and 59 per cent want to see more information on packs and in-store.

Brands are bound by legislation to label ingredients and ensure formulas, whether natural or not, are safe and that claims are substantiated. Yet there is no legal definition of “organic” or qualification for “natural” in labelling, as applies in the food industry. The International Standards Organization is reviewing guidelines, but until then, consumers must do their own research.

In the absence of regulation, communication is even more important and it’s not what you say but how you say it. “Consumers want to engage with brands and their stories on a deeper level,” says Sarah Coonan, beauty buyer at Liberty. “If brands want to claim a social conscience, they must weave it through their brand DNA.

“Buyers are savvier than ever before. They read ingredients or notice if packaging is not recyclable and they will call brands out on it.”

It is no longer enough to just support a charity or include organic ingredients to be perceived as ethical. Brands that blend efficacy, desirability, transparency and social conscience resonate with today’s ethically minded consumer.

“The challenge for the big industry players is how to translate their social responsibility programmes in a retail environment. It often remains invisible to the consumer and means they can be viewed with scepticism,” says Ms Coonan.

Brands also need to be proactive if they want to avoid scrutiny, like the scandal around microbeads polluting marine environments that has led to a ban by 2020. Or the current debate on the environmental credentials of wet wipes. There is currently no legal requirement to divulge a wipes material if it is classed as disposable.

Acting responsibly

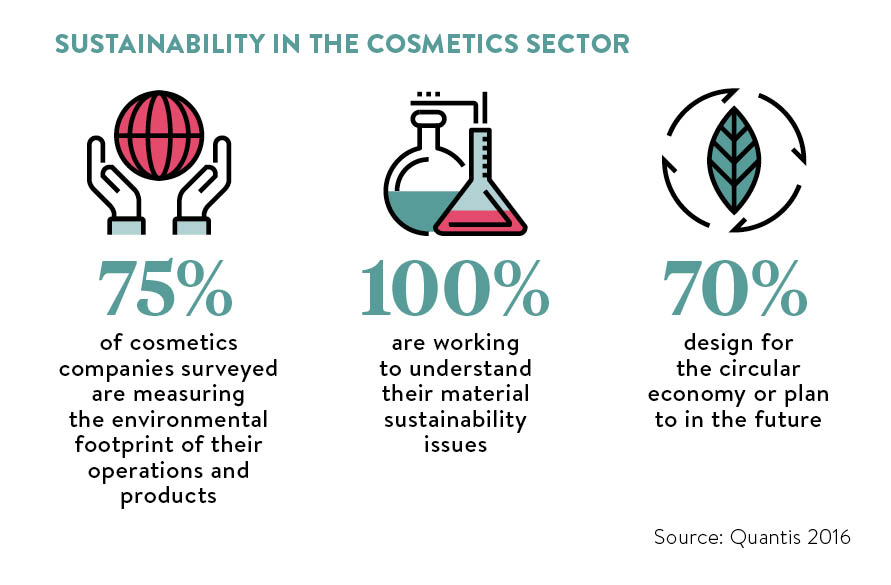

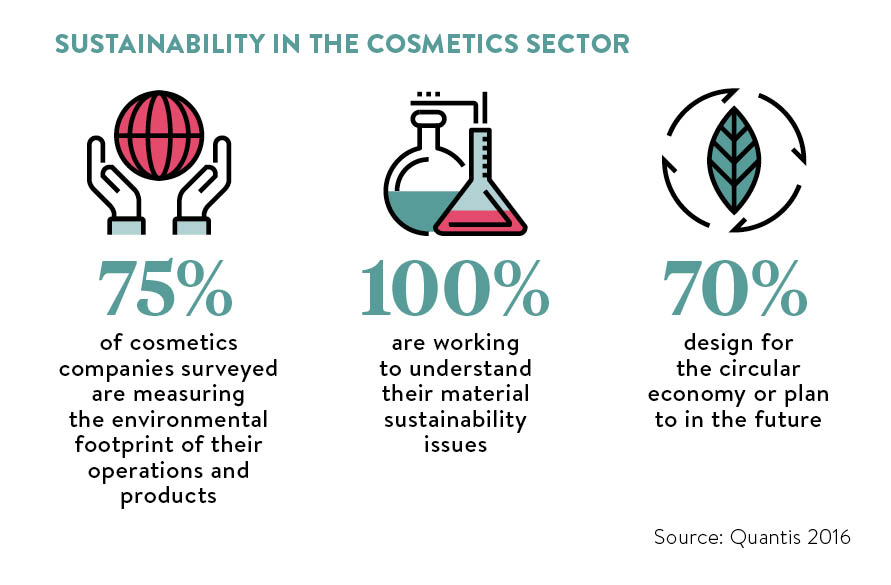

From sustainable sourcing and traceability of ingredients, biodiversity protection, water conservation and reduction of waste to landfill, industry leaders are already working hard in these areas.

Aveda has pioneered the use of post-consumer recycled packaging and bio plastic derived from sugar cane. Parent company Estée Lauder is developing a UK rainwater harvesting system to provide 14 per cent of water demand. L’Oréal’s 2020 Sharing Beauty With All sustainable commitments include responsible sourcing of palm oil. Its production is recognised as a source of deforestation, a main contributor to biodiversity loss and climate change.

In 2016, The Body Shop turned 40 and renewed its ethical commitment – enrich not exploit – with the aim to be the most truly sustainable global business. It is the first cosmetics company to commit to the industrialisation of AirCarbon, a thermoplastic alternative to oil-based plastic, created with methane and carbon dioxide captured from cow dung, which would otherwise be released as a greenhouse gas.

Innovative solutions

Industry experts agree innovation is key to meet the future demands of consumers and environmental realities, with green chemistry and product afterlife likely topics of debate.

“Standard sustainable packaging options are still slim,” says Ms Kilgore. “And while there are regulations on ‘overpackaging’ in terms of how big your package is versus how much usable product goes in, it would be forward-thinking for the industry to also regulate packaging based on recyclability. I’d like to propose that, just like in footwear, the industry goes light.”

She also points to a need to retrain consumer-thinking. For example, weights currently added to cosmetics imply quality, but they end up in landfill for years.

A paradigm shift is required, with sustainability seen as a creative opportunity, not a limitation, says Amy Christiansen Si-Ahmed, founder of the first socially conscious fragrance brand Sana Jardin. “We need to go above and beyond traditional sustainability models and initiatives limited to a net neutral impact to achieve real, lasting change,” she says.

Consumers and industry both have their part to play.

The beauty wellness trend