The beauty industry is rife with paradox. Here we have a business that historically catered for the patriarchal system rather than women. From the men who ran publicly traded cosmetic companies all the way down to the hetero-normative, cisgender aesthetic sold to consumers – at its very core, beauty was a man’s business.

And yet this industry became a platform for women to succeed. From Bobbi Brown and Essie Weingarten to the millennials who have disrupted the marketplace with on-demand services and YouTube channels, women have reclaimed their rightful place atop the beauty business. They have shifted the prevailing message from often highly sexualised subservience to female empowerment.

Catering for all

In spite of this, the very definition of beauty has remained narrow and discriminatory, a fault for which the industry has been criticised over the years. Diversity is a far broader term than it was 30 years ago, and the battle is no longer about equality for women, but for all kinds of women and, beyond that, a dissolution of gender binarism altogether.

Consider the black and mixed-race population in the UK. This contingent has doubled in last ten years and, according to predictions from the Office for National Statistics, will reach 35 per cent of the total population by 2035. The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising estimates that black women spend some £4.8 billion on products and treatments, with Afro-Caribbean women spending six times more than their white counterparts on their hair. But even with such an impressive spend, ethnic groups remain drastically underserved and under-represented in the industry and at the beauty counter.

The dearth of products that suit black skin prompted Leomie Anderson, a 22-year-old British model who has worked for Tom Ford and Victoria’s Secret, to voice her frustration on Twitter with ill-equipped make-up artists. Her words echo the Instagram tirade of South Sudanese model Nykhor Paul, who lambasted the industry for catering exclusively for white girls.

Even though product innovation for ethnic skin is low, representation seems to be growing

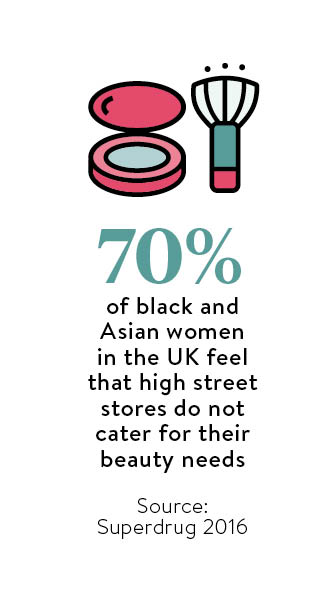

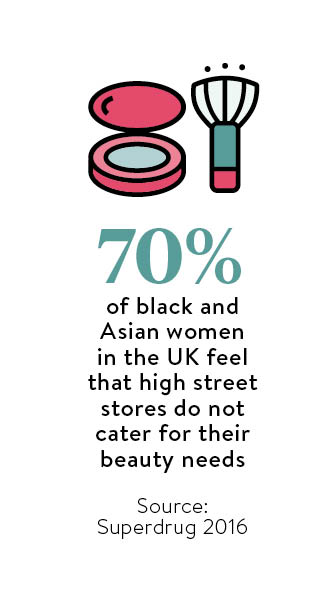

Their protests are merely a reverberation of what is happening on the high street. According to research by Mintel, larger retailers do not perceive the ethic market as presenting a large enough return on investment. This claim was challenged by Superdrug, who revealed that 70 per cent of black and Asian women felt the high street did not cater for their beauty needs, a statistic it aims to amend by encouraging major brands to cater for darker skin or import stock from the United States where darker shades are readily available.

“Things are a lot better than they were when I was a teenager,” says Ateh Jewel, a beauty journalist of Nigerian and Trinidadian heritage and the woman behind an award-winning blog for black women. “But there’s still a long way to go. Most brands have two or three darker shades out of a possible twenty for white women.

“Things are a lot better than they were when I was a teenager,” says Ateh Jewel, a beauty journalist of Nigerian and Trinidadian heritage and the woman behind an award-winning blog for black women. “But there’s still a long way to go. Most brands have two or three darker shades out of a possible twenty for white women.

“And even then, those two or three shades are unlikely to work for most women because companies don’t appreciate the sheer diversity of different undertones in black skin. There’s caramel, blue and golden, there are cool tones and warm tones… It’s not just about adding a bit of red or orange to an existing formula.”

In many instances, Ms Jewel has been told point blank by designer brands that “we don’t have anything for you”. Only ranges founded by professional make-up artists seem to understand the complexity of black skin, but the expertise of Bobbi Brown, MAC Urban Decay and Make Up For Ever comes at a price.

Even though product innovation for ethnic skin is low, representation seems to be growing. Kenyan-Mexican actress Lupita Nyong’o has lent her striking features to Lancôme while Betty Adewole appears in ads for Tom Ford. Liu Wen and Joan Smalls, on the other hand, frame the archetypal beauty of blue-eyed Constance Jablonski in campaigns for Estée Lauder.

Whether their inclusion is a socially conscious move on the part of cosmetics giants or a means to conquer highly profitable emerging markets such as Asia and Africa remains to be seen. “I do think brands are becoming more aware,” says Ms Jewel. “But they also realise there’s money to be made.”

Gender bias

Economics don’t quite justify one other critical arena of diversification in the beauty industry – gender fluidity. Gender-neutral generation Z has spawned internet stars who don’t necessarily think of beauty in a binary fashion. To wit, leagues of mascara-clad boys have taken Instagram by storm with their make-up tutorials.

Granted, there is a long tradition of male make-up artists in the industry, but none have operated with quite the same gender-bending gusto or visibility as MANNYMUA (Manny Gutierrez) or YouTube sensation Patrick Starrr (Patrick Simondac), larger than life characters with more power than most female beauty editors.

Brands responded to the new paradigm with uncharacteristic speed, seemingly oblivious to the fury it would surely incite among its more conservative customers. The phenomenally talented 17-year-old James Charles is CoverGirl’s first cover boy while in the UK, The Plastic Boy, Gary Thompson, has been signed by L’Oréal Paris for its TrueMatch foundation campaign. Benefit, Maybelline and a host of other brands have teamed up with make-up-loving men on their social media accounts.

MAC, a brand that has consistently broken convention since the early-80s, has collaborated with transgender star Caitlyn Jenner and started a Transgender Initiative that provided $1.3 million for the community. Make Up For Ever, meanwhile, has featured “between genders” model Andreja Pejić in its campaigns.

The goal, of course, is not to sell make-up to men. That demographic is too tiny for such a large campaign. These brands are sensitive enough to see what’s happening in the world and are fearless enough to ride a cultural wave towards “genderlessness”. The uproar was predictable: “Idiot men are not supposed to do that.”

Whether or not the gender-neutral generation remains in the employ of multinationals is up for grabs. But, as a statement, their visibility is needed now more than ever, especially in the wake of countless hate crimes and a palpable resistance by right-wing internet trolls. Yes, it may be a sensational move, but it demonstrates that, in spite of its faults, the beauty industry is still capable of changing with the times.

Catering for all