After the first demonstration of his company’s Clubcard scheme in 1994, a startled Tesco chairman Lord MacLaurin remarked: “What scares me about this is that you know more about my customers after three months than I know after 30 years.”

The rise of e-commerce in the last two decades has seen an extraordinary increase in the amount of data and the speed with which it can be gathered. Three months seems a very long time to wait for customer data these days.

“When I started, companies were throwing away data because it was just too expensive to hold,” recalls Edwina Dunn, who with her partner Clive Humby developed the Clubcard programme for Tesco. “The cost of analysing data has really come down and the tools have evolved.”

Shopzilla, for example, now has ten years’ worth of information on some 100 million people. It tells the comparison shopping firm what websites they have visited, which brands they are interested in and, with the use of “similarity” algorithms, scores shoppers according to the probability of them clicking on one advertisement or another.

“Advertisers also use companies like us to age attribute, that is to predict changes in users,” explains Rony Sawdayi, vice president, engineering at Shopzilla. “Take someone who is a new mum. In the first month she may be interested in baby furniture, but after four months that will not be appropriate.”

The cost of analysing data has really come down and the tools have evolved

Much of this information can be encapsulated in rules. So-called programmatic marketing is increasingly dominating the advertising business. “Media buying is one of the main drivers for big data,” says David Fletcher of media agency MEC UK. “The more data signals you can gather, the greater the extent those data signals can be played back in a meaningful way.”

Online there are 70 billion automatic auctions each day lasting microseconds. The auctions decide who will serve up an advertisement to a website visitor based on what is known about that person and the needs of an advertiser. Even when a consumer fails to buy, there are ingenious ways of retargeting that person with e-mails and additional ads.

Social media now plays an increasingly important role in gathering customer data. When customers access sites via social media log-ins, they allow marketers to tap into the personal data held by Facebook, Twitter and other services.

“People expect their location will be collected – their online visits, their use of credit cards, their e-mails and tweets,” says James Calvert of advertising agency FCB Inferno. Nonetheless, most digital advertisers do not have access to information that can be tied to one individual, but identify groups of users who are likely to be more interested in a particular product or service.

Even when data is used anonymously it can lead to problems for retailers. The Target supermarket chain in the United States was contacted by an irate father after his daughter’s buying habits led the store to believe she was pregnant and to send her mailshots for pregnancy-related products. The young woman had not told her father about her condition.

The real challenge, says Professor Joe Peppard of the European School of Management and Technology in Berlin, is in discovering new knowledge and that involves asking the right questions. “There is consumer resistance,” he points out. “The Snowden [spying] revelations have made people sit back and think about data and what they may be revealing.”

Some commentators point to the rise of social media such as Snapchat, which deletes messages after they have been read, as evidence of a desire by consumers for greater privacy.

For Jenny Thompson, head of data and analytics at 360i London, all this is premature because most marketing specialists have still to move off first base. “The fact is that the biggest task facing marketing directors today is not exploiting big data, but getting their existing data into a position where they can identify how to use what they already have to create a competitive advantage,” she says

Case Study

RAPID RESPONSE

Speed and agility are the essence of Formula One motor racing and so it is with the IT that supports Lotus F1 Team.

In a sport where hundredths of a second mark the difference between winning and losing, the ability to collect and analyse large amounts of data quickly is a key factor.

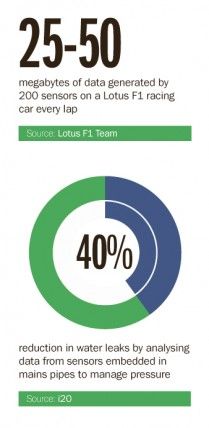

On the track, 200 sensors on a Lotus car spew out data at the rate of 25 to 50 megabytes per lap, while in the lab engineers have two weeks to design and test new components. This hectic activity has over the last two years seen an 80 per cent growth in the amount of data Lotus generates.

“You can never have enough data,” says Michael Taylor, Lotus F1 Team’s IT director. “The more you produce, the more you know. We’ve learnt it is imperative to have the right infrastructure. The key is to log everything and provide a correlation between events.”

Lotus has recently signed a deal with the storage company EMC as part of an IT makeover. The arrangement, which lasts until 2016, will enable Lotus to have access to a petabyte of storage that will hold performance, design and aerodynamic information connected with Lotus cars.

In practice sessions and during a race, Lotus engineers receive real-time radio telemetry and more detailed “cable data” retrieved by plugging an ethernet cable into the car. Basic data about competing cars is also available.

Analysts in the pits and back at the team’s headquarters use this data to shape the race using algorithms that not only alert engineers to important events, but are capable of learning from them and carrying out some tasks automatically.

Speed of response is a crucial aspect of the technology used to process big data

“When we mash that data together it allows us to ensure that systems are working properly and to analyse their performance,” says Mr Taylor. The team is now able to analyse car aerodynamics in two hours, rather than the two weeks it took previously.

Speed of response is a crucial aspect of the technology used to process big data. For analysis of historical data offline, many big e-commerce companies favour the Hadoop software ecosystem, which relies on massively parallel computing.

When it comes to operational data – information that must be analysed as it comes in – NoSQL is the market leading database. The software trades speed and agility for consistency when handling unstructured data.

“Four or five years ago we used a regular relational database,” says Mike Williams, software director at i2O Water, a company that runs a service for water companies which reduces water leaks. “Then we re-architected our platform and looked at how data was stored, analysed and retrieved.”

i2O Water opted for an event-driven architecture in which different services communicate with one another via event brokers. “All the brokers can be written in different languages and we don’t care if data is duplicated,” says Mr Williams.

The company uses a NoSQL database called Apache Cassandra to handle data coming in from thousands of sensors embedded in its clients’ water pipes. These sensors enable i2O Water to detect falls in water pressure and adjust the pressure to minimise leaks. i2O Water estimates that managing water pressure more actively reduces the volume of leaks by around 40 per cent.

The plunging cost of hardware means supercomputers are increasingly being applied to data-intensive modelling. Renewable Energy Systems (RES) installed a new Cray system earlier this year that has made it much easier to find likely sites for wind farms.

The additional power has improved accuracy by enabling analysts to review ten years’ worth of meteorological data, compared with the one year they previously had to work with.

“We are able to generate a historical time series in a matter of minutes. Analysts can then mix historical data with real-time information to make better decisions,” says Clément Bouscasse, RES forecasting and flow modelling manager.

The downside is that the 100 terabytes of storage for the models is filling up fast.

Case Study

RAPID RESPONSE