-

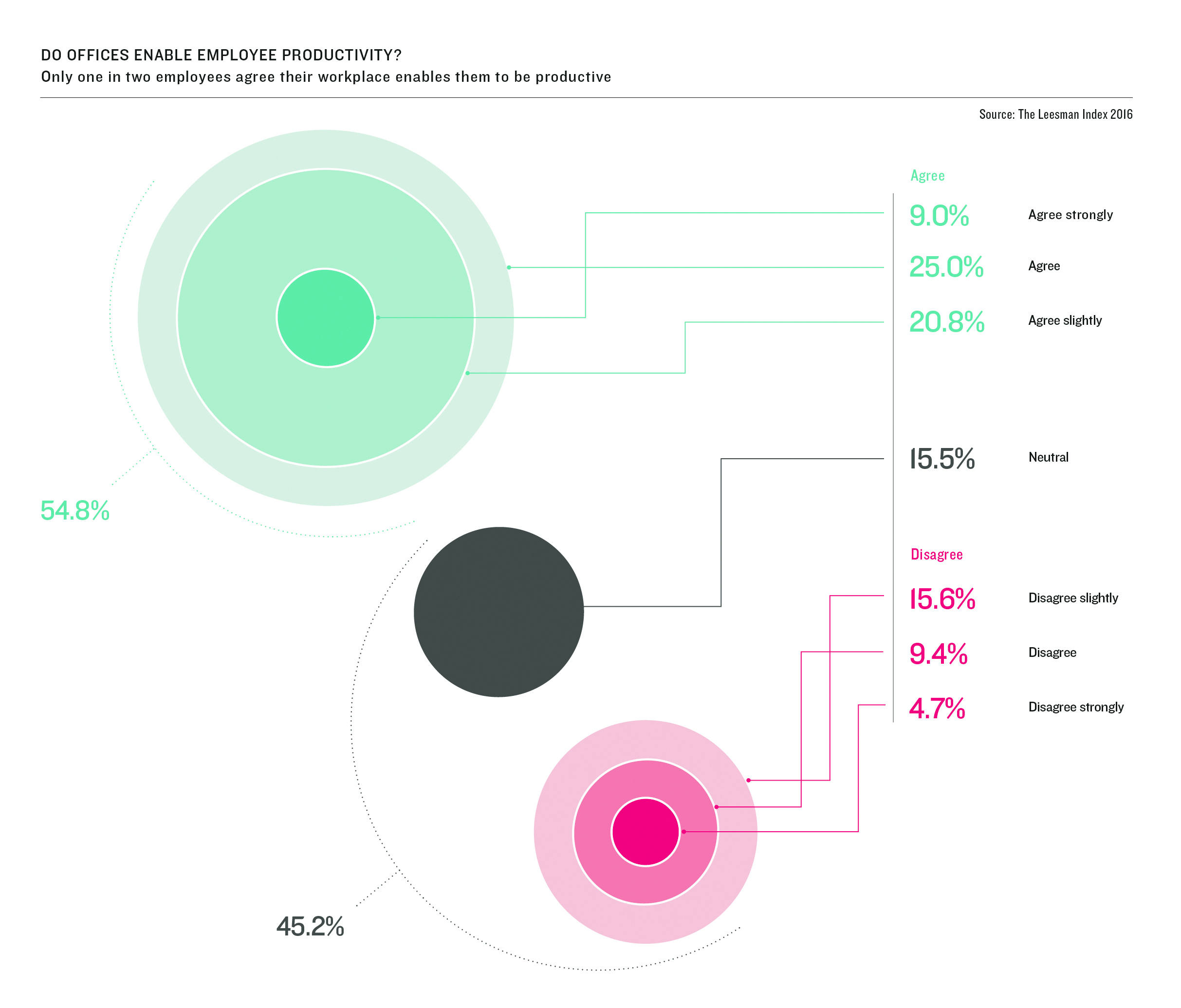

Only one in two employees agree their workplace enables them to be productive

-

Workplace is the second biggest cost in any organisation after salaries

-

It’s time to start measuring the impact of workplace on employee productivity

Attaining greater productivity is a holy grail that continues to elude and excite some company executives. Business leaders, economists and politicians are united in wanting to ensure firms get the most from their staff at the lowest possible cost. But where should they start? The first step is to measure it using a uniformly accepted method. According to H James Harrington, the renowned expert on quality and performance improvement, if you cannot measure something, you cannot understand it. If you cannot understand it, you cannot control it. If you cannot control it, you cannot improve it. But then of course, as British economist Charles Goodhart identified in the 1970s, specifying the wrong organisational measures can have negative, and even disastrous, consequences.

While economists measure it as the volume of output per hour worked, many companies and industries use their own indices that have more relevance to their business. A financial services firm might use revenue per broker while an advertising company might focus on the number of accounts, and a back-office services business might measure the volume of work completed in a certain time. And the chief executive will just want to know that whatever is being measured can be linked to future company profits.

But whatever measure is used, there is an opportunity for the workplace to enable greater worker productivity. For industry 4.0, higher productivity comes from better problem-solving and decision-making as well as more effective employee and client interactions. These measures all point to a shifting psychological contract between employer and employee.

Smarter not more

Unfortunately, The Stoddart Review found that the typical response has been to carry out utilisation studies and look to increase workplace occupant density. These projects may deliver increased occupant density, but they confuse spatial efficiency with productivity and our investigations found that these terms were being far too casually transposed. ‘Saving real estate costs by increasing occupation density is a false economy if it results in cluttered, noisy ‘one-size-fits-all’ environments that frustrate people and actually hinder effective work,’ says Bridget Hardy, strategic advisor on smart working at the Department of Work and Pensions. ‘The key to increasing density effectively is mobility — with the freedom to choose coupled with a choice of environments that suit different types of work and personal preferences.’

Research carried out for The Stoddart Review shows that progressive firms understand that productivity is a human outcome, not an organisational one. There is growing awareness that the route to productivity is no longer just about delivering more, but also about delivering in a smarter way, through facilitating more effective interactions that result in more creative solutions, and higher quality targets.

As function heads and industry professionals continue to conflate the efficiency of space with the productivity of employees, it is essential that the board challenges, expects and seeks good answers to a broad range of questions, and that it’s equipped for discussions such as these:

- Do our workplaces actively support employees doing the job we employ them to do?

- Do we understand whether different roles within the organisation have differing workplace needs?

- Do we know whether employees are proud of their workplace?

- Do we know if the workplace is helping to create a strong sense of community?

Beyond open plan

There is now a clear understanding that the workplace itself can be a barrier to higher productivity. While some organisations are still at the stage of implementing open-plan solutions for cost reasons, others have accepted that a large, open-plan office does not necessarily result in greater collaboration, more efficient working or world-beating innovations. They now realise that open-plan offices can also be noisy, distracting, irritating and counterproductive.

A wealth of studies past and present has demonstrated this. A 2013 study by the University of California found that office workers were interrupted as often as every three minutes by digital and human distractions and that once these distractions occurred, it could take as long as 23 minutes to get back to the task in hand.

The route to productivity is no longer just about delivering more, but also about delivering in a smarter way

A 2016 study from Auckland University of Technology found that, as work environments became more shared (with ‘hot desking’ at the extreme end of the spectrum) not only were there increases in demands, but co-worker friendships were not improved and perceptions of supervisory support decreased. The authors said that ‘distraction caused by overhearing irrelevant conversations is a major issue in open-plan office environments’, and that this distraction was negatively linked with employee performance and perceptions of the workplace, and with stress.

Stress matters, and not just for reasons of compassion. A 2014 Willis Towers Watson Global Benefits Attitudes survey found that levels of workplace disengagement increased significantly when workers experienced high levels of stress. The study, which looked at 22,347 employees across 12 countries including the UK and US, showed that more than half those employees who claimed to be experiencing high stress levels also reported disengagement.

Gallup’s 2013 State of the Global Workplace Report estimates the cost of disengagement to the UK’s workforce at £52 billion to £70 billion.

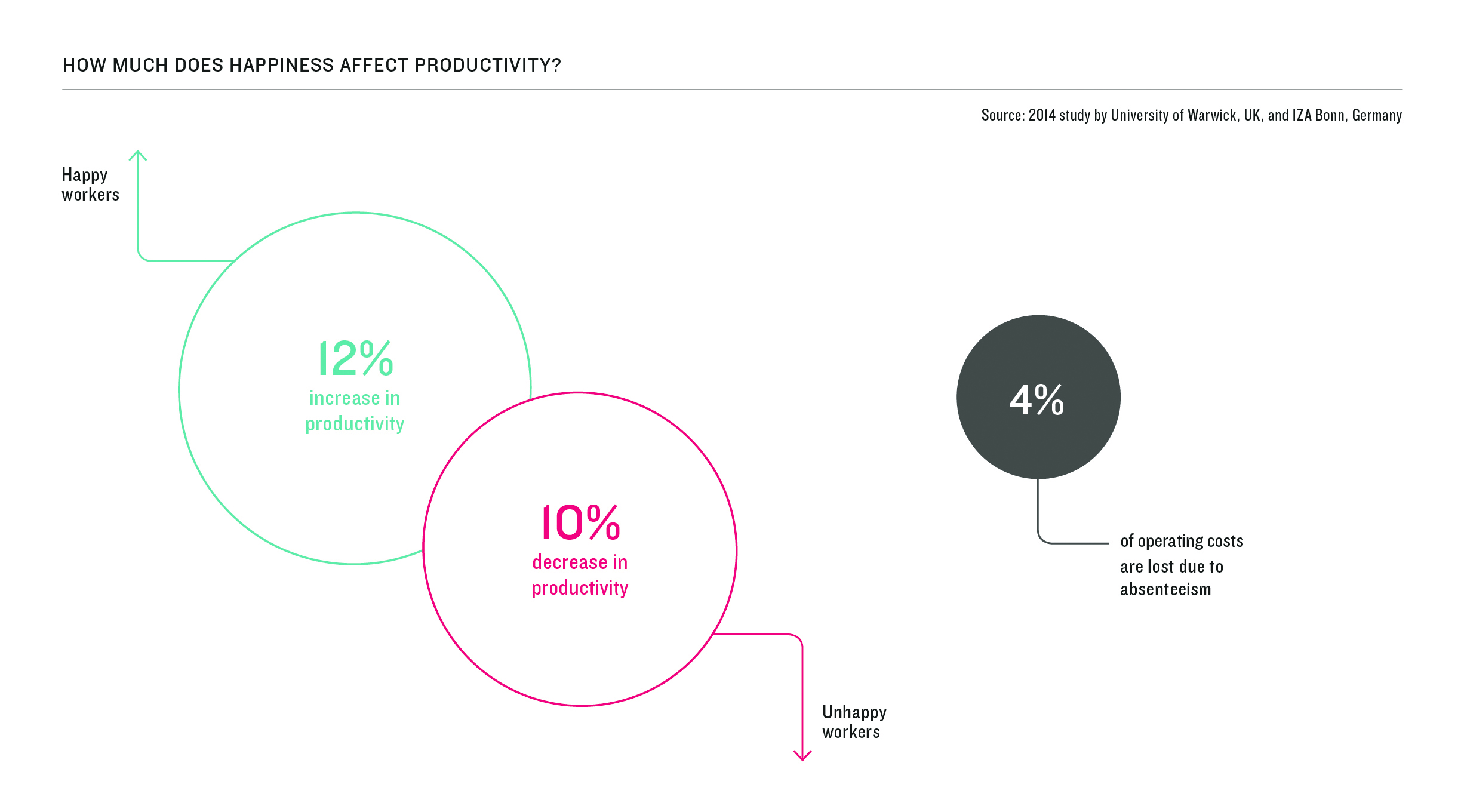

Gallup methodologies use nine key employee engagement outcomes: customer loyalty/engagement; profitability; productivity; turnover; safety incidents; shrinkage; absenteeism; and quality (defects). The Stoddart Review’s observation is that workplace underpins every single indicator.

The human opportunity for UK plc is clear; it’s time to start measuring the impact of workplace on employee productivity.

The danger of measuring the wrong thing

The consequences of identifying the wrong measure of success can be disastrous. Take Wells Fargo, for instance, which was recently fined $185 million. Wells’ employees are incentivised to cross-sell products to existing customers and the number of new accounts opened are deemed the level of success. Due to perhaps a combination of pressure and greed, 5,300 employees opened roughly 1.5 million fake bank accounts without customers’ consent, resulting in the mass accumulation of bogus fees. Before the scandal came to light, these employees were getting credit for opening new accounts and meeting their sales goals. The business failed to check whether any of the accounts actually had any money inside. Coca-Cola suffered a similar measurement misjudgment in the 1980s when it completely changed its soft-drink formula based on the results of a series of sip tests. While the testers preferred one sip of the sweeter formula, nobody has just one sip of Coke – they drink a whole can. And the company didn’t test whether a whole can of the new formula was as popular as just one sip. It wasn’t. They received over 40,000 complaints and had to switch back to the old formula. In both cases, huge expense and effort could have been saved if the companies had given more consideration to the measure of success before proceeding.