Emerging markets may have netted investors some of their best returns in recent years, but the boon hasn’t come from Africa’s 27 stock markets. African investors have sunk more into assets like government debt and private equity than publicly listed companies.

The malaise has affected the continent’s big exchanges from South Africa’s JSE, the oldest and largest equity market in Africa, Nigeria’s NSE and Egypt’s EGX, right down to Rwanda’s tiny exchange in Kigali, with just seven listed companies.

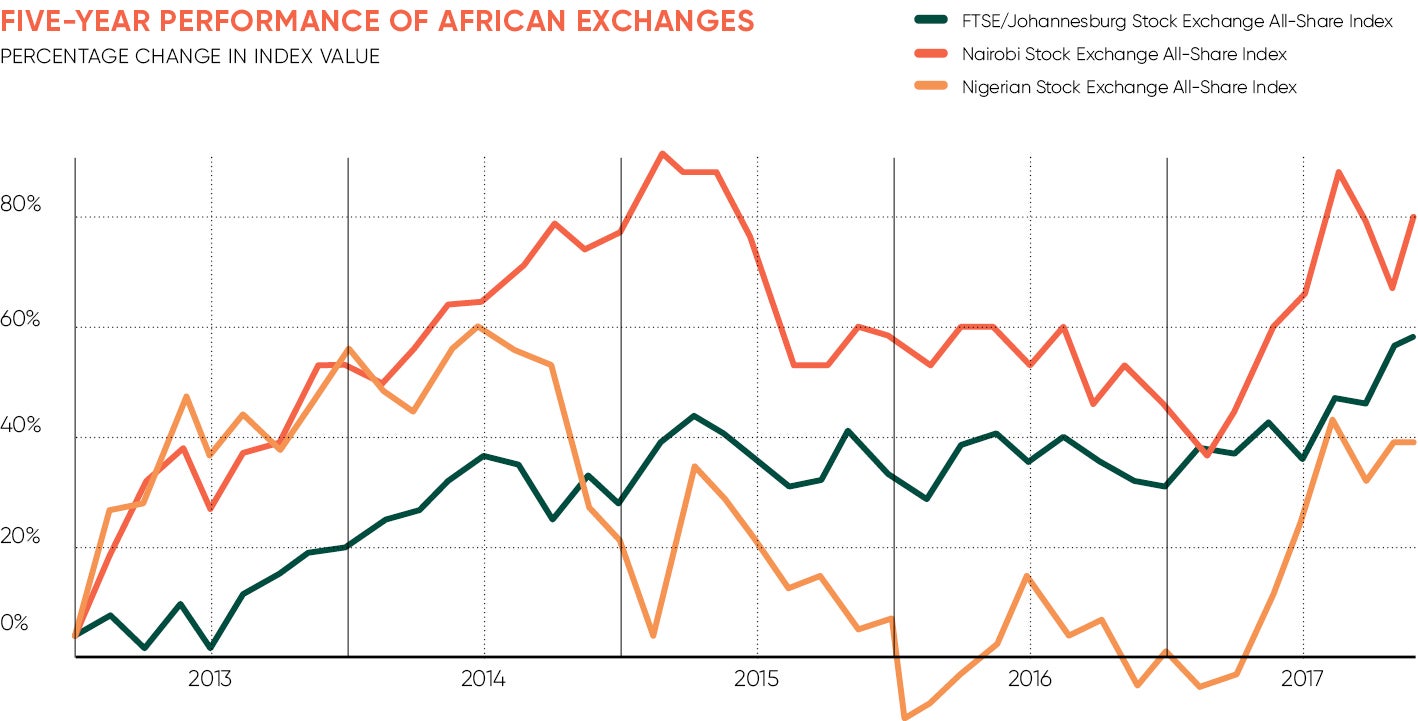

Now, as Africa’s biggest economies edge back into growth and currency storms blow over, so equity markets are poised for a comeback, fuelled by corporate growth linked to growing populations with new spending power. Its good news for Africa’s savers looking to invest and emerging corporates in search of finance, and it has Africa’s exchanges busy beefing up their offering.

African equities have been clobbered by the sharp depreciation of many local currencies against the surging US dollar. “In the last three years we have seen the same rate of depreciation we would expect to see over a ten-year period,” says Ayo Salami at Duet Asset Management in London.

The impact on stock exchanges has been two-fold. On one hand tumbling local currencies have dissuaded equity investors, unable to hedge the currency risk. On the other, demand for equities has cooled as Africa’s central banks tightened monetary policy and hiked interest rates to try and prop up their tumbling currencies. As a consequence many investors stuck to investing in less risky and higher yielding government bonds.

The currency crisis also unnerved foreign equity investors for another reason as Nigeria and Egypt introduced exchange controls, stopping investors repatriating money. “You have to be in your 50s to remember when Africa last had currency controls. It came as a shock that retrograde policies could still be implemented,” says Mr Salami. Both countries have now eased capital controls and the gloomy mood music that had settled over the region’s biggest markets is fading away.

The initial public offering of MTN Nigeria, a subsidiary of the South African telecoms giant, is hoped to encourage smaller rivals to go public

Stock exchanges are determined to capitalise on the interest and attracting new listings to boost liquidity is their top priority. In Nigeria all eyes are on the telecoms sector where MTN Nigeria, the subsidiary of the South African giant, is preparing to list next year, in a first for the sector. It’s a result of government arm-twisting after the company broke rules, but the hope is that MTN will encourage smaller rivals, such as Globacom and Airtel, to follow suit. In Egypt the government is preparing to sell a stake in the oil company ENPPI in the first privatisation for 12 years, kick-starting a mass government IPO (initial public offering) programme across the economy.

Stock markets are betting on Africa’s private equity bonanza coming their way

Stock markets are also betting on Africa’s private equity bonanza coming their way. The continent’s first wave of private equity investors have exited without using the stock exchanges, selling to trade investors or new private equity funds instead. “Africa has seen a great deal of private equity flows, but none of that activity has benefited the capital markets,” laments veteran investor Joseph Rohm.

Proponents are now focused on private equity’s next cycle for things to change. “Private equity is still raising a decent amount of money,” says Mr Salami. “Once this slows down, we should start to see more private equity exits via the stock exchange.” Private equity is also the perfect precursor to going public. It prepares company bosses for tough questions and broadens the shareholding beyond the founders.

Elsewhere, African companies have also been dissuaded from listing because they are too small and it’s too costly; an IPO or private placement involves hiring advisers and advertising. Family-run businesses are put off by the disclosure and reporting requirements, and don’t see the marketing benefits either.

Africa’s stock exchanges are trying to change these perceptions. Kenya has introduced tax incentives to encourage companies to list and small exchanges have sprung up to tempt small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Bourse Régionale des Valeurs Mobilières (BRVM), a regional stock exchange based in Abidjan covering eight francophone countries, is the latest to allow small businesses to list with fewer and less restrictive conditions.

In response to the low number of listings on its SME index GEMS, Kenya’s NSE has started a mentoring programme “We want to give interested companies a realistic and practical feel of the listing process,” says the Capital Markets Association’s Paul Muthaura.

One answer to the liquidity problem is for stock exchanges to merge. BRVM has 40 stocks and is fully integrated, with member countries sharing a single electronic quotation platform and a common regulator. In East Africa, Rwanda is leading efforts to create one stock market, but so far enthusiasm is muted. Many countries regard a stock exchange as a sign of nationhood, like having an army.

But stock exchanges are modernising in other ways. Manual markets are becoming automated, and linking to developed market settlement systems and indexes. Rwanda’s stock exchange has pledged to extend its trading hours and bring down the settlement time. Nigeria has just launched a NASDAQ market surveillance system in line with global best practice.

Initiatives to boost foreign investment include dual-listings, something the JSE has done for years, but which Nigeria accomplished for the first time in 2014 when oil producer Seplat listed on both the London and Lagos exchanges.

In other developments index provider MSCI’s Frontier Markets Index has steadily increased its weighting of African stocks, boosting portfolio flows and appetite to list, as a result.