Cryptocurrencies have captured people’s imagination and it’s easy to see why there is so much excitement. They are growing exponentially, with bitcoin, the best known cryptocurrency, showing growth of more than 1,000 per cent since the start of the year, according to XE.com.

Though bitcoin is the best known, there are hundreds of other cryptocurrencies being traded in the market. But what exactly are they?

Cryptocurrencies are simply a medium of exchange, like the US dollar, pound or euro, but they only exist digitally. They rely upon encryption technology to control the creation of units of the currency and to confirm transactions. That technology is called blockchain.

As the currency does not exist in a physical form, it is imperative that it cannot be replicated or spent more than once. To avoid this, the technology publishes all transactions in a public record with multiple versions of that ledger distributed online so they may be checked and updated automatically.

Those ledgers are then protected by attaching a number of new transactions to the ledger, with the old version frozen and encrypted. This is known as a block and each block contains a copy of the previous ledger. This makes them easy to check and verify, but difficult to copy or alter. As new blocks are added, so a chain of blocks is created, which gives the technology its name.

As well as being efficient, transactions are cheap as there is no middle man, such as a bank, taking their margin from each party.

The growth of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies has encouraged commentators to compare its success to bubbles of the past, such as tulip bulbs in the early-17th century or the dotcom crisis of 2000.

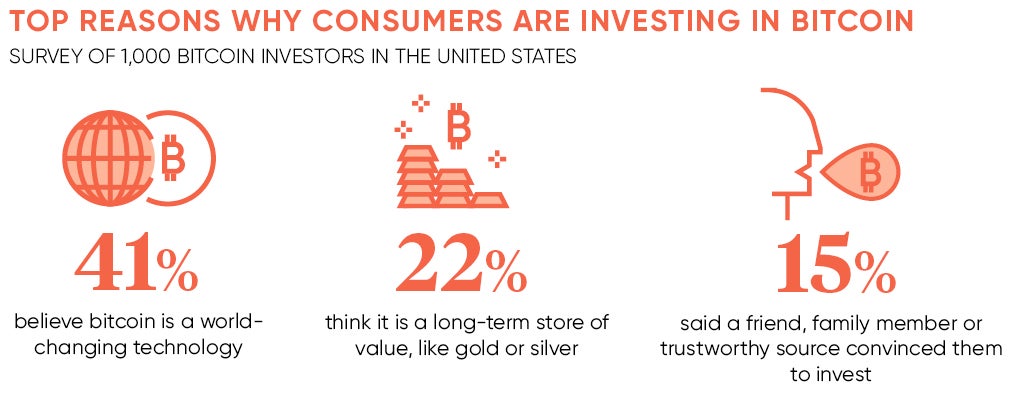

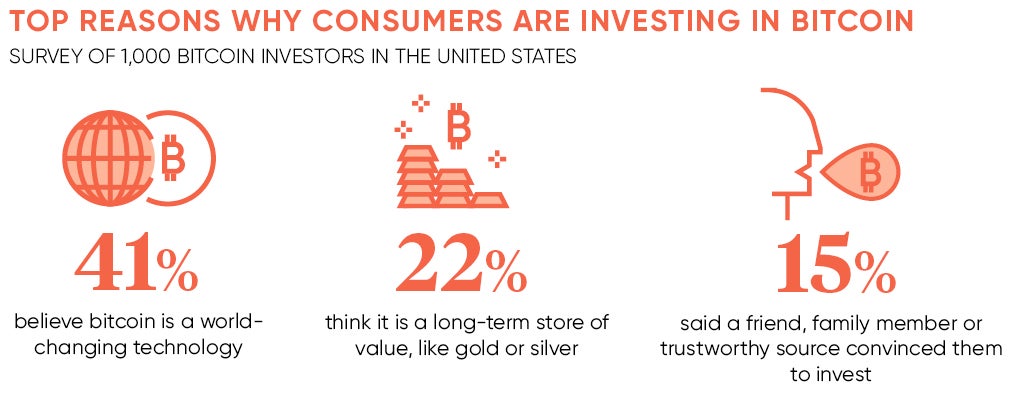

Information is in short supply, encouraging investors to base their hopes on past performance – the classic way to fall foul of a bubble.

Information is in short supply, encouraging investors to base their hopes on past performance – the classic way to fall foul of a bubble.

The main reason people accept and trade a cryptocurrency is because others recognise it and trade in it, and they view it as a currency.

It is beyond government control, being decentralised and limited; there is no tap to increase the supply and, rather than a currency, it behaves like something between an equity and a commodity.

Transactions that are executed in these currencies only become visible to authorities when the money is exchanged into a fiat currency, such as dollars, pounds or euros, and surfaces in a bank account.

UK regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, does not regulate cryptocurrencies, but just because something is unregulated does not mean there are no liabilities.

Tom Shave, a partner at wealth manager Smith & Williamson, says HM Revenue & Customs leaves it up to the individual to interpret or take advice, but asserts that the existing framework will apply.

“If trading a crypto, its gains will be subject to capital gains tax and there could also be VAT due on capital gains against an underlying token,” says Mr Shave.

Investors who may wish to realise some gains should not be dissuaded from doing so, warns Guy Stephens, technical investment director at wealth manager Rowan Dartington.

Just as there are hundreds of cryptocurrencies, many with their own platforms, there are also dozens of exchanges for investors to trade their holdings

“This may make investors reluctant to sell their holding in bitcoin because they are sitting on healthy profits and don’t want to be stung with capital gains tax. This is the mistake that many made back in the dotcom bubble and, rather than realising taxable gains, they got hung, drawn and quartered when it collapsed.”

Just as there are hundreds of cryptocurrencies, many with their own platforms, there are also dozens of exchanges for investors to trade their holdings.

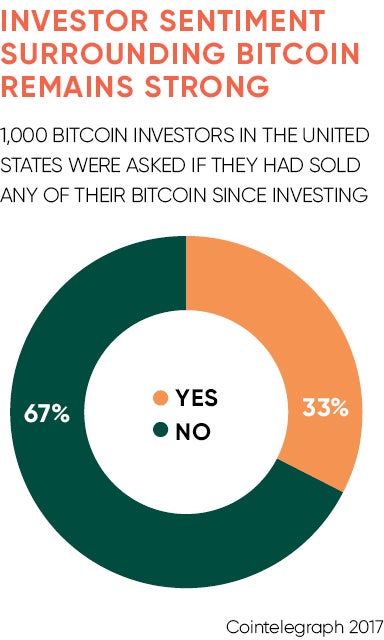

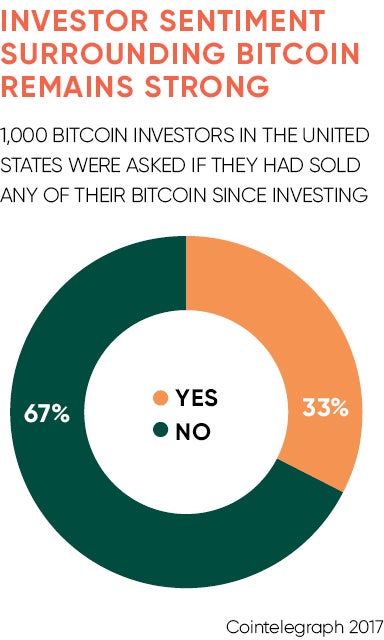

Like any other asset, values are determined by supply and demand, though without any outside regulatory influence, prices are driven largely by market sentiment and speculation.

This has resulted in eye-watering levels of volatility in recent weeks. Fears about a cancelled software update, the creation of bitcoin futures, the abandonment of plans to split bitcoin to create a larger supply and general fears about a bubble saw the cryptocurrency’s values drop, rapidly losing 25 per cent. Yet, within a period of a couple of weeks, it had set new record highs again, reaching more than $11,000.

Such volatility will worry the individual investor, but may offer comfort in these trying times.

Being tied to no government, economy or currency may provide a little insulation from the geopolitical rollercoaster. The power of populism has driven a lot of short-term volatility in traditional markets from the Brexit vote, through to the fall of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and it is not played out yet.

With notable exceptions, cryptocurrencies may be viewed more favourably by governments that can see the benefit of transparency and efficiency for at least some of their functions.

Banks, too, are looking to exploit blockchain efficiencies and 2018 could see it start to become a mainstream technology.

Blockchain is seen to be the mojo for making the internet of things a reality with devices able to exchange data, and pay for services securely and independently.

There is massive growth in initial coin offerings or ICOs, which have rapidly become a means for new blockchain businesses to raise funding.

Tiana Laurence, a founder of blockchain company Factom and author of Blockchain for Dummies, says this is fast replacing venture capital investment in this area. “This space is expected to grow from 600 ICOs in 2016 to around 5,000 next year,” she says.

It’s success is clear, says Ms Laurence, who bitterly reflects on a year spent on the road visiting investors to raise a little over $8 million, when a friend of hers seeking to launch a competitive service raised $10 million in six to eight weeks over the summer with a website and white paper.

The demand comes from investors, who believe the value of the coin they receive in exchange for funding will increase, but the risks, as in any startup, are great. But with little more than a brochure as a business plan, let the buyer beware.