Given all the hype, it would be easy to think smart beta had just rolled off the fund management industry’s new product line.

In fact, the basics of the strategy were developed by financial wizards decades ago. It works like this: equity investors swap market capitalisation indices, such as the FTSE or S&P 500, which weight companies according to the value of their shares, for ones that group stocks according to different factors, including the low volatility of their share price or that they look cheap relative to their earnings.

But as smart beta assets under management balloon to $800 billion, with some forecasts estimating this will reach $1 trillion by 2020, so smart beta has moved into the spotlight.

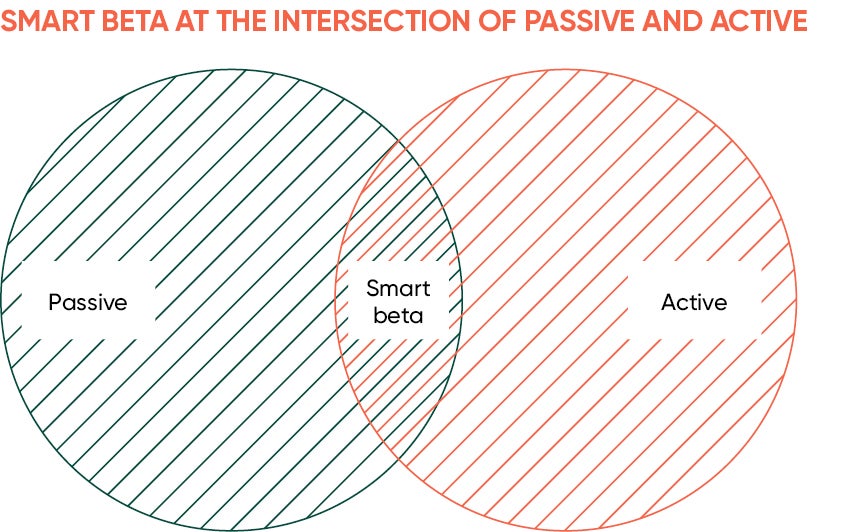

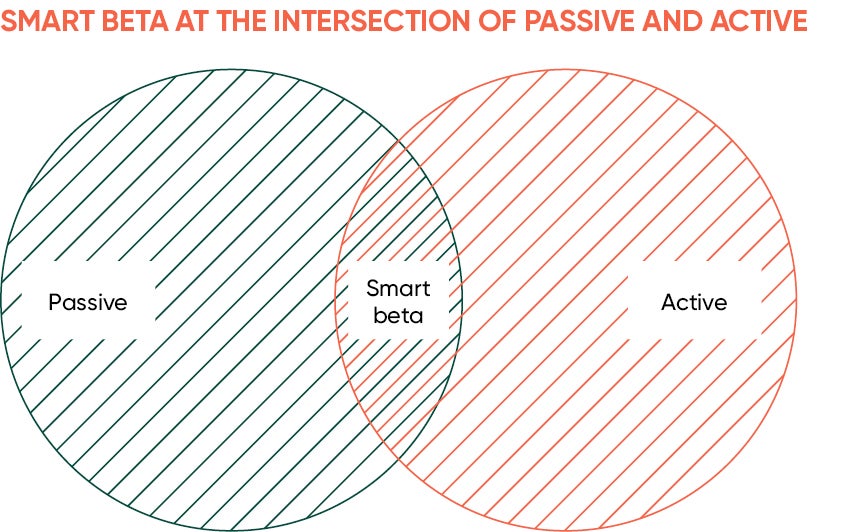

The reason why it is suddenly the hottest trend in finance is found in its name. Smart beta slots in between the two most used words in an investor’s lexicon: alpha and beta. Beta refers to the market return and involves nothing more than buying an index-tracking fund in a passive, cheap and relatively low-risk strategy. Alpha is much cleverer and involves active management, or stock-picking, by investment managers to try and beat the market. It’s expensive and difficult.

In an investor’s nirvana, smart beta combines the two, using rules-based screens to select specific groups of companies or factors with tracker funds. It has also dished up strong returns. According to Vanguard, between 2000 and the end of 2014, smart beta outperformed the traditional “dumb” index by around 3 per cent a year.

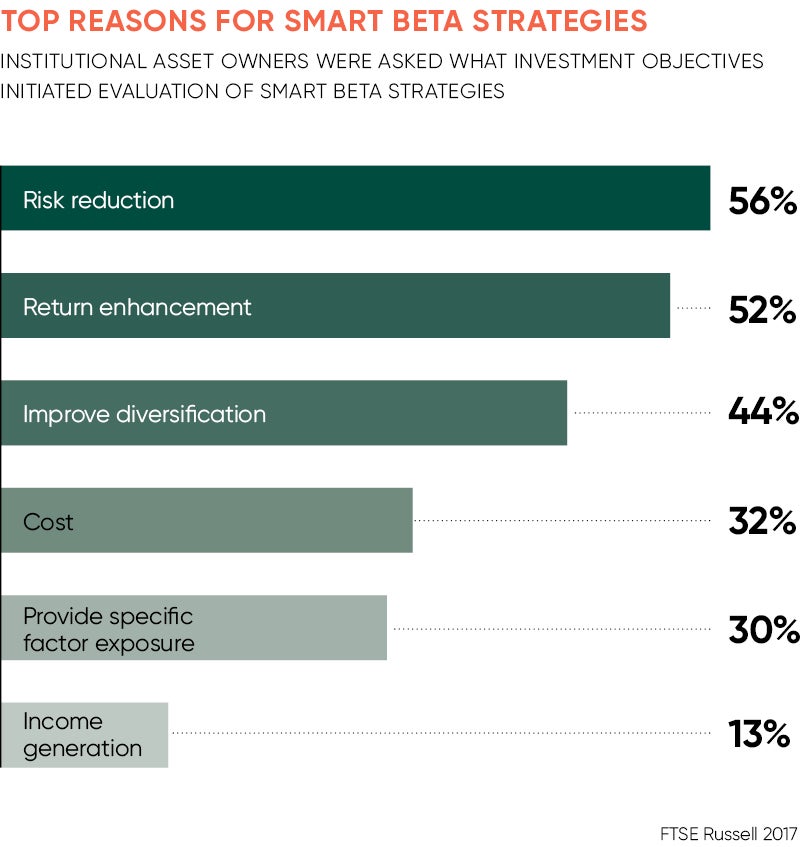

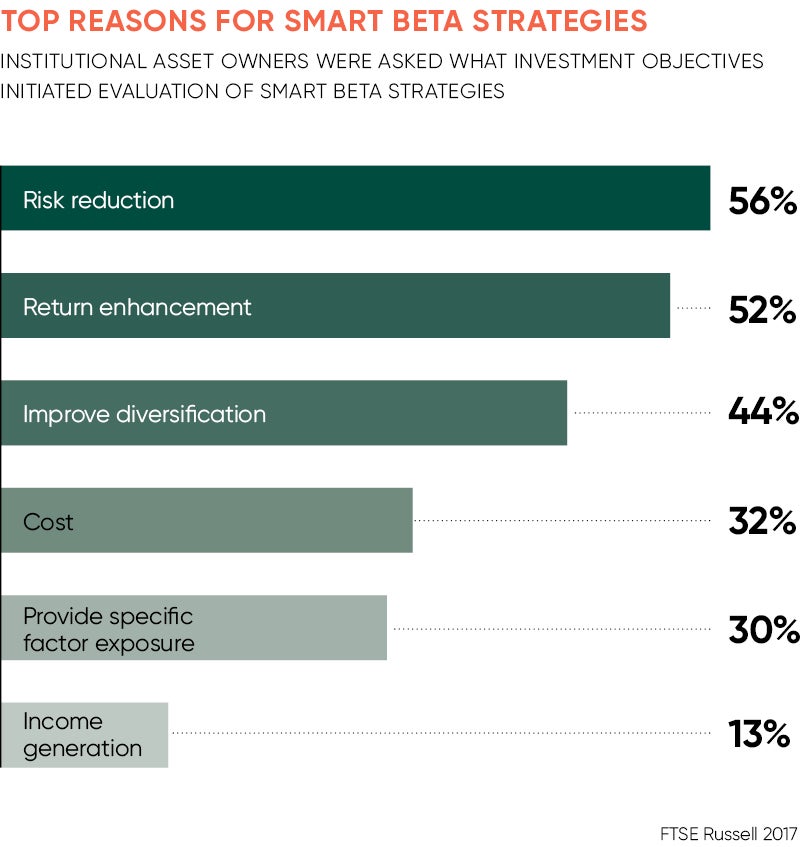

Smart beta has also found favour as an alternative to market capitalisation, which gives big companies the biggest slice of the index, even when they are overvalued. Buying the index in 2000 during the technology bubble meant massive exposure to the ensuing “tech wreck”. Now different exposures or factors provide nuanced strategies that could fare better in today’s market.

These factors include “value” and “low volatility”; “momentum” where investors gain exposure to stocks with strong historical performances; “yield” favouring companies with higher-than-average dividend yields; and “quality” which groups stocks with strong balance sheets.

But in this ever-expanding web lie risks. Factors should be carefully chosen as they do not all perform the same. “Folks need to make sure they understand how each strategy is different because one might outperform another,” says Tony Davidow at the Schwab Center for Financial Research in New York. The more established factors have more historical data to measure their success and have been more rigorously back-tested than new ones.

“We like fundamental because the strategy is well developed. Investors need to know how factors work and what happens if they become a larger strategy,” cautions Mr Davidow, touching on the most worrying aspect of the smart beta craze.

Smart beta, or at least the most popular factors including low volatility, could hold the seeds of its own destruction. As it becomes more popular, so the weight of money threatens to erode the anomalies or inefficiencies that promise the return. It prompted Rob Arnott, head of California-based Research Affiliates and a pioneer of smart beta, to warn that smart beta could go “horribly wrong”.

When too much money goes into something it can suddenly unwind

Mr Davidow counters that not all investment is chasing the same smart beta strategies. Even so, Towers Watson investment consultant Phil Tindall points out that the 2007 “quant quake”, when algorithms coded by quantitative investment teams collapsed, is a reminder of what can go wrong with these similar types of strategies.

“When too much money goes into something it can suddenly unwind,” he says. In the last 12 months, £2.2 billion has flowed into “value” exchange-traded funds compared with £315 million during the previous 12 months, according to Morningstar.

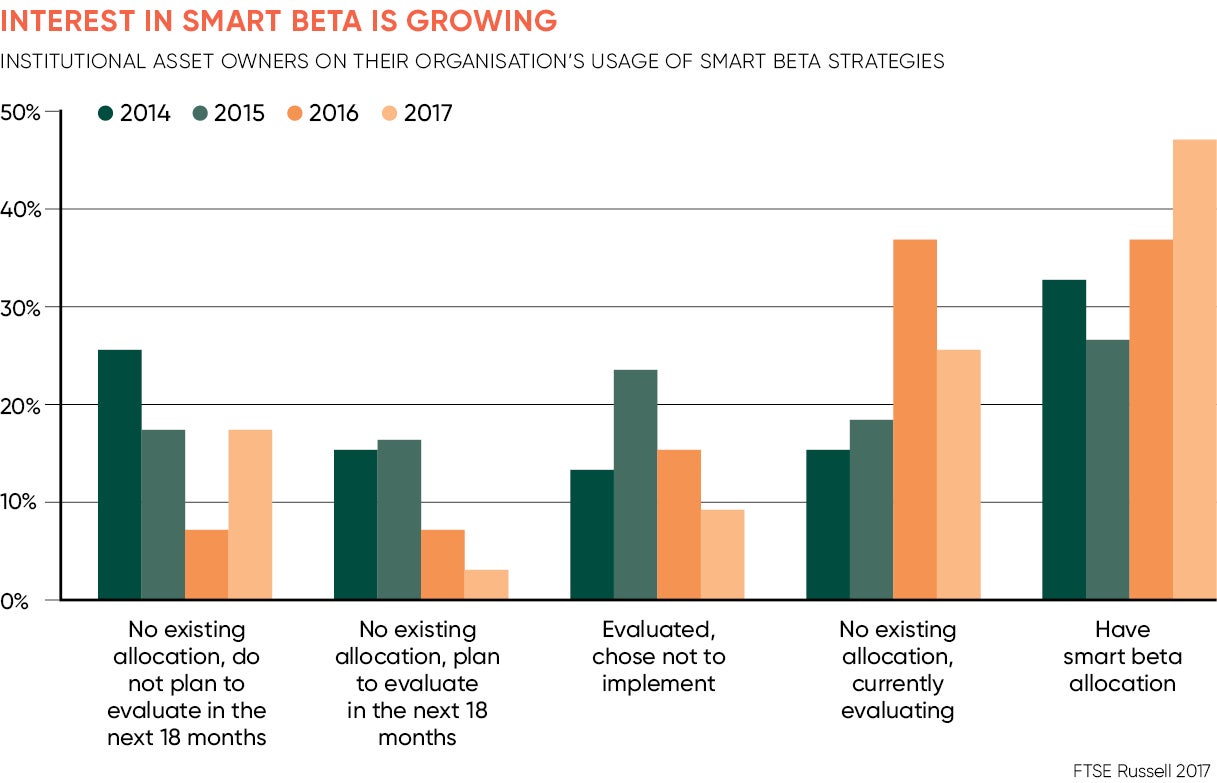

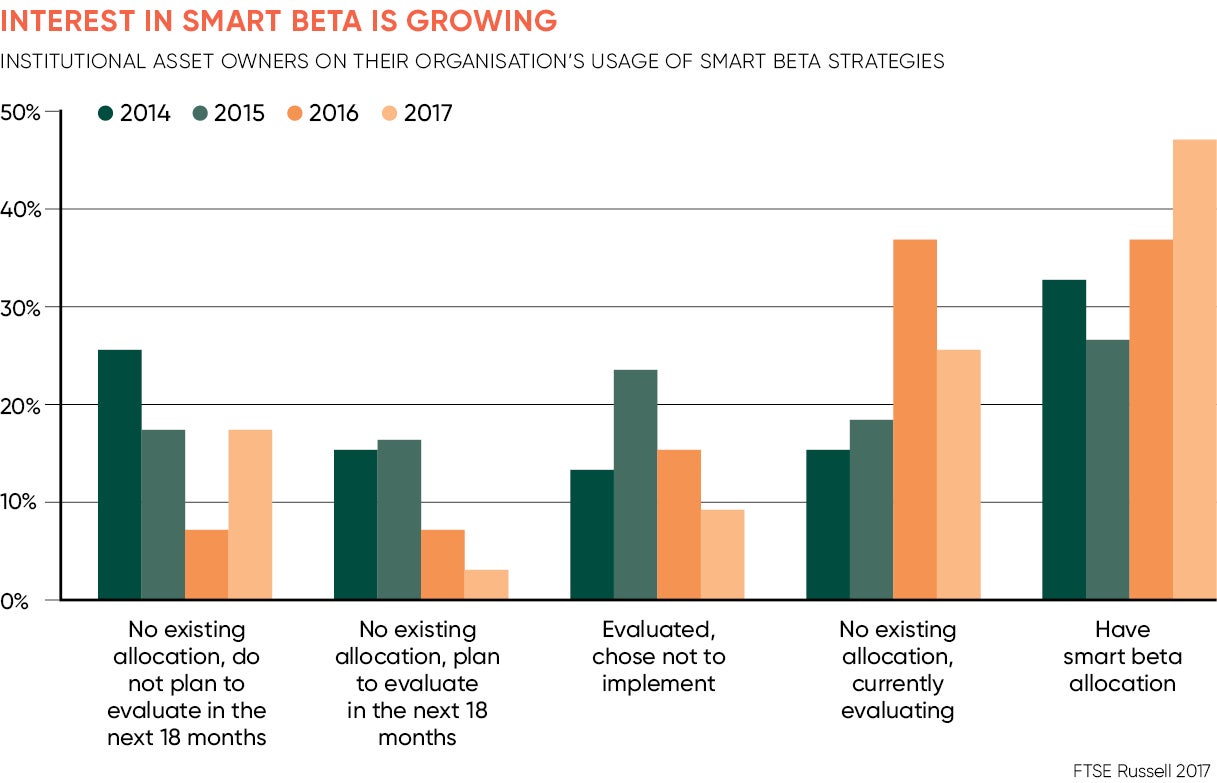

And it is the explosion of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), using smart beta strategies that also has some experts worried. Big institutional investors, such as Denmark’s ATP and US pension fund CalPERS, have developed bespoke and nuanced smart beta strategies, constructed to complement their overall portfolios, and taking into account turnover and liquidity. Institutional money in smart beta strategies is estimated at $40 billion by Towers Watson, in a survey of 300-plus investors.

But many investors access the strategy via publicly traded ETFs which have packaged up smart beta in a cost-effective and easily tradeable vehicle for a broader investor base. It’s a designer fashion at bargain prices that holds dangers, warns Dr Alessandro Laurent at London-based Seven Investment Management, who creates bespoke smart beta funds for clients, rather than invest in ETFs or with external providers.

“ETFs are dangerous for their simple strategies and the ETF provider offers no come-back if it all goes wrong. These funds are just tracking exposure to a certain factor; it’s massively oversimplified. In every market there are good and bad products; it’s about differentiating between the two,” he says.

Trying to time the market to pick up on rising factors is also risky. “There are some trends,” acknowledges Dr Laurent. “If value has suffered, it does tend to mean it will do quite well in the future; value also tends to do worse in a low interest rate environment. But you don’t want to go in and out of factors depending on the market.”

The big passive, and active, fund managers such as Aberdeen Asset Management and BlackRock have responded to the shifting market by launching their own smart beta funds. And it’s set to spread to other asset classes. Fixed-income and commodity indices are prime areas for future growth, say experts excited by the opportunity to gain access to more of the time-tested ideas that used to be the preserve of active managers.