A month into the coronavirus lockdown, National Rail and London Underground use had fallen by 99 per cent and 96 per cent respectively compared to early February. Bus passenger numbers plummeted by 88 per cent and airport departures had declined significantly.

Now lockdown is starting to ease, mobility is tentatively rising. But with the government advising against using public transport if possible, and many educational institutions and office buildings remaining closed, the daily commute could be consigned to history.

A study by the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) has highlighted that preferences for working and socialising remotely post-lockdown will see a move away, at least in the short term, from the infrastructure demand patterns that existed prior to the pandemic.

Drawing on YouGov polling data, ICE found that 61 per cent of UK adults support increasing the frequency of remote working. Some 32 per cent think there should be a transition to a permanent at-home working environment where possible, while 44 per cent are likely to avoid travelling on public transport networks.

Director of policy at ICE Chris Richards says in the immediate post-lockdown, pre-vaccine phase, public trust in existing transport infrastructure will need to be regained, possibly by modifying trains, tubes and buses for social distancing and increased ventilation.

Protesters hold a banner that reads ‘NHS not HS2’ by a gate to the HS2 site near Euston Station

This comes at a price when finances are already massively constrained, however. While transport companies are absorbing the costs and losses for now, in the future it could result in a realignment of services, says Richards.

“We might need to consider if the same frequency or intensity of use is needed if suddenly people are working three or four days a week from home,” he says. “Then there’s the wider question around other types of assets needed to support public mobility.”

Changing travel modes

Dr Enrica Papa, reader in transport planning at the University of Westminster, who is running a research project in response to COVID-19, says people could start using cars more if they lack other options.

“Those who were using public transport are now using cars. We need to find a way to live with the virus and still travel sustainably, so in the short term there should be investment in local infrastructure to stop a car renaissance,” she says.

Dr Susan Kenyon, principal lecturer in transport, politics and society at Canterbury Christ Church University, agrees. She adds that COVID-19 has disrupted people’s travel behaviour, rather than changed it completely.

“Studies show even if the commute is taken away and substituted for ‘virtual mobility’, people still move about the same amount, they just redistribute their travel behaviour,” says Kenyon.

“If the government wants to encourage people to work from home, it needs to understand who can and who can’t do it and focus more on local, rather than national, infrastructure. People will need to get to nearby shops, rather than from Manchester to London in record time.”

On May 9, the UK government announced a £250-million emergency fund to help people travel without public transport. In England, the money will help establish “within weeks” pop-up bike lanes, wider pavements, safer junctions, and cycle and bus-only corridors. E-scooter trials will also be brought forward from next year to June this year. In London, mayor Sadiq Khan has also tried to curb car and underground use by increasing the congestion charge and creating large car-free zones.

Levelling up

Going further, to encourage remote working in the future, Kenyon says virtual mobility could be designed and orchestrated under transport planning authorities. There could be investments in better broadband and infrastructure such as “tele-cottages” built into new housing developments so people can work from home more comfortably. “Otherwise, people will return to normal when the pandemic is over,” she says.

So if people are to travel less in the future, it raises questions about whether transport infrastructure investments, such as the High Speed 2 rail project (HS2), are still appropriate.

The government green-lighted HS2, which will connect London, the Midlands and the North, serving eight of Britain’s ten largest cities, in February, suggesting it still believes the service will be needed in the future.

“There’s no conversation around stopping this project because the long-term drivers are still there; we need to decarbonise rapidly and we expect urbanisation to continue,” says Richards.

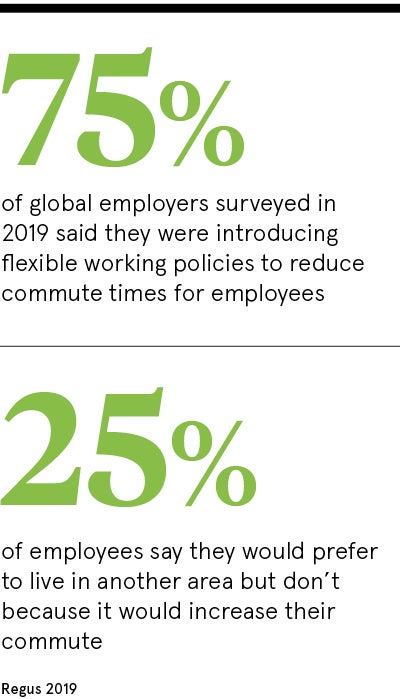

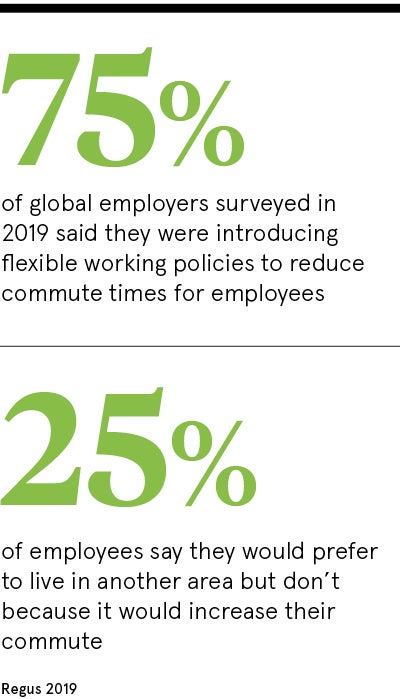

There are already anecdotal stories of people considering or actively moving further away from business centres because they feel they can work from home more and travel into work less. Could this help achieve the government’s plan to level up and squash regional inequalities faster?

“If you take levelling up to mean all regions of the UK have the same amount of investment and infrastructure to support what they need, then potentially no,” says Richards. “However, if people who used to work in London and commute can now live in Manchester and still earn the same wage, the amount of money flowing into the area will increase.”

While there are few certainties, it is known that people travelling less has reduced overall carbon emissions. But Claire Haigh, chief executive of Greener Journeys, says there are fears these gains could be lost or made worse if the huge fall in public transport demand and revenues sees services go bust.

“Public transport has a critically important role to play in decarbonising the transport system, as rising demand for car and van travel is one of the main reasons why transport emissions remain stubbornly high,” she says.

Looking forward, Richards says everyone is simply trying to understand “how much of the current changes will stick, versus it just being for the short term”.

“But overall, there’s an appreciation that if we do act we can address big things like air quality and carbon emissions in cities. It’s doable. There’s definitely a positive that can come out of this,” he concludes.

Changing travel modes

Levelling up