One of the greatest clinical quests could be entering its endgame. The search for an HIV vaccine has been a tortured 30-year battle against a formidable pathogen that has left a trail of misery in its wake.

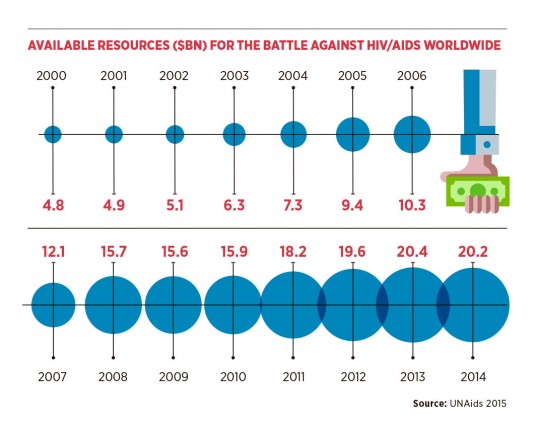

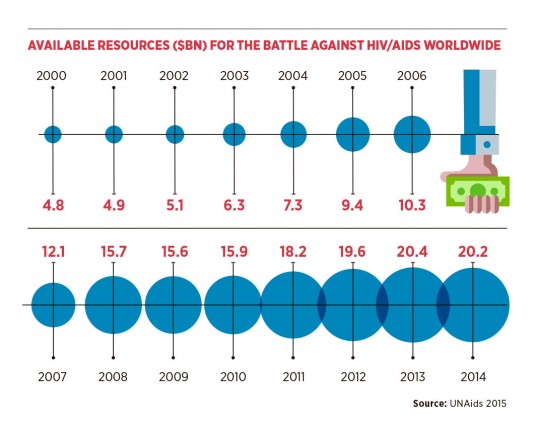

Repeat statistics can desensitise, but the awful truth is that two million people are infected with the virus every year and, despite the towering triumph of antiretroviral drugs in dampening the disease, HIV infection keeps growing.

But the glimmer of hope from a surprise trial in 2009 is about take the next step towards establishing a prized vaccine. It may be on the horizon, but it is far from the medical mirage that has blighted a generation of scientific endeavour.

The glimmer of hope from a surprise trial in 2009 is about take the next step towards establishing a prized vaccine

A study in South Africa will come to a crucial point within four months when investigators will make a “go or no-go” decision on an efficacy trial on a vaccine with a 50 to 60 per cent prevention target.

“A moment in history”

“Making a vaccine will be a moment in history,” says Dr Larry Corey, president and director emeritus of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centre and principal investigator of the Hutch-based HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which conducted the study. “There is an energy and momentum, and we are cautiously optimistic.”

The hope comes from trials in Thailand which, in 2009, found a vaccine that provided 30 per cent protection against HIV acquisition by using a vaccine regimen that elicited a novel set of antibodies which could slow down the virus. The caution comes from long years of being thwarted by a complex enemy that refused to play by the rules.

“The progress with vaccines has been very different to the advances in antiretrovirals,” adds Dr Corey, who was part of a Nobel Prize-winning effort to discover a cure for herpes. “It is pretty remarkable that you can now live for 40 to 50 years on these medications and die of cardiovascular disease when it was once a condition with a median death time of six months.

“Preventing HIV/Aids has been a tougher road to slog down. It has been harder scientifically to understand how to interrupt acquisition through an immune response, and we have gone through a lot of fits and starts with models we predicted would work not doing the job.”

Vaccines for diseases in polio and measles create the antibodies that attach to the virus and prevent them from entering the body. But the biologically complex HIV protein, known as an envelope, comprises three loosely connected structures which mutate making it difficult to land neutralising agents. The virus is also very efficient in killing off immune cells, and becomes a moving target as it mutates and leaps around within the body.

The vaccine from the 2009 trial, named RV144, contains three HIV-1 genes delivered into the envelope by an engineered viral vector to stimulate an immune response. Its success in stopping four out of ten infections was a revelation, but a series of follow-up studies conducted by an international team of scientists showed that the people who received the vaccine and made specific types of antibodies were protected from HIV. The hope is that this next set of vaccines will produce even higher levels of these antibodies and elevate the success rate to 60 per cent.

Other groups of scientists are working on ways to manipulate the HIV virus’s envelope into a vaccine that makes the type of antibodies that neutralise the virus from infecting human cells. This is a reworking a strategy tried in the 1980s that now becomes possible by advances in research and technology.

“We had a good concept, but did not realise how hard it would be and how clever the virus was in disguising itself,” says Dr Corey. “We moved on to using T cells, but that did not work effectively so this is plan C. Pushing it up to 50-60 per cent is the first step, then we have to try to make that 90 per cent and I believe that is achievable.

“The need for a vaccine is as strong as ever. We can do great things by testing and treating people, but in the US we still have 50,000 new cases a year. It kills over a longer time now, but it is still an epidemic. Look what happened when we had 2,000 to 3,000 cases of Ebola. The HIV figures have gone from horrific to just horrible, but we have become inured to them because they are so out of scale.”

The scientific and HIV community is on edge waiting for the critical decision whether to go for the full trial, which is slated to start next July in South Africa where the burden of Aids is at its highest.

Understanding HIV

Sir Andrew McMichael, professor of molecular medicine at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, Oxford University, believes our understanding of HIV has improved over the last decade, making a vaccine possible, but echoed the note of caution.

“For a flu vaccine, for example, we would hope for 100 per cent protection so 30 per cent is not terribly good, but is a lot better than nothing. And if that result can be repeated, and that is a big if, but if it is repeated, then I think we have opened the door slightly,” he says.

Vaccine development could take up to ten years

“I think that it will be possible to improve on that 30 per cent and get it up to 50, 60, 70 per cent and then we really would have a vaccine. But that whole process would probably take at least five years to get to that more efficient vaccine and then another five years to roll out to give to large numbers – we are talking millions of people.”

In the meantime, advances in PrEP – pre-exposure prophylaxis, a daily pill for people at high risk of getting HIV – are providing a good measure of protection. But it only works to stop the virus taking hold and is not like a vaccine – a solo or short series of inoculations – which teaches the body to fight off the infection naturally for a number of years.

Dr Corey concludes: “We need a vaccine because we have not got HIV under control. Backing off is not an option and we need to continue to put the pedal to the metal. We have elements of containment, but the reality is that it is spreading throughout the world and we can only stop it with a vaccine. We must continue the quest.”

ELITE CONTROLLERS

Clinicians are on the hunt for a group of HIV patients who could be the X-men and women who can conquer Aids.

Known as “elite controllers”, they have been infected with the virus, but have managed to keep it at bay for decades without needing any drugs.

A group of 80 have been monitored in the San Francisco area, but the aim is to collate data from 2,000 worldwide to see if their health profiles provide clues to a new preventative drug or a cure.

A group of 80 have been monitored in the San Francisco area, but the aim is to collate data from 2,000 worldwide to see if their health profiles provide clues to a new preventative drug or a cure.

It is thought that elite controllers have a number of genetic factors that combine to ward off the virus. The research challenge is to identify these factors from a myriad of mechanisms and determine a combination present in all of them.

A research programme at the Laboratory for Tumour and Aids Virus Research, University of California in San Francisco, is recruiting volunteer elite controllers and hoping to unpick the cell coding that makes them so efficient at dealing with HIV.

The prize would be a therapy that allows people to move off antiretrovirals, which can have side effects, and stay healthy for their lifetimes.

“A moment in history”

Understanding HIV