It is roughly 30 years since the world was traumatised by HIV and Aids. Back in the 1980s becoming infected with HIV was a probable death sentence, but for those with access to treatment, this deathly prognosis has been lifted for more than a decade. The advent of antiretroviral drugs enables people with HIV to reduce their viral level to the extent that they cannot pass on the virus and can live near-normal lives.

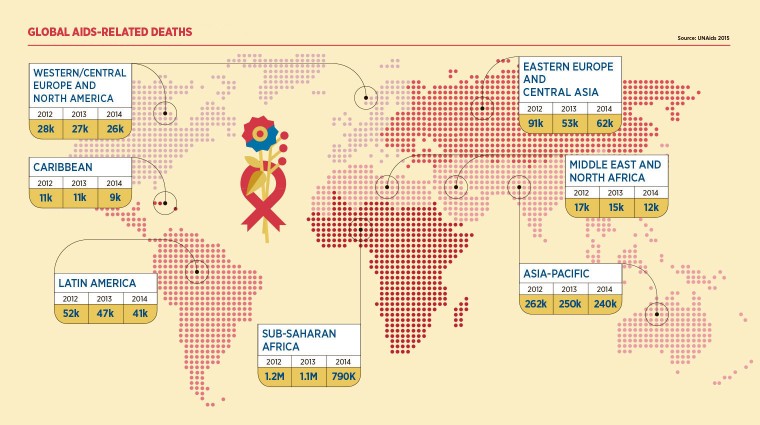

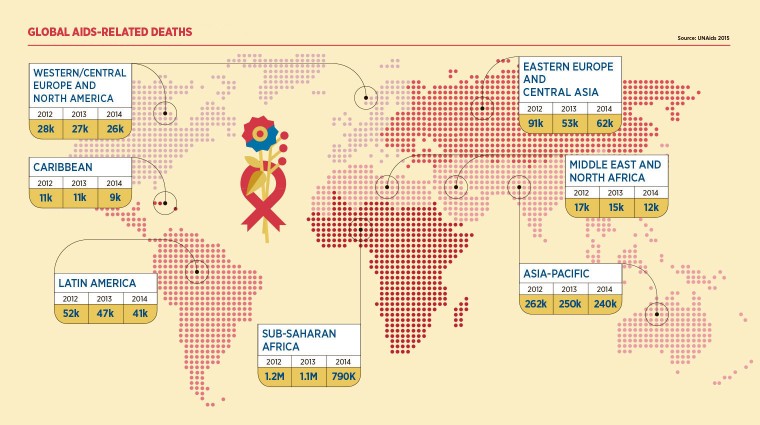

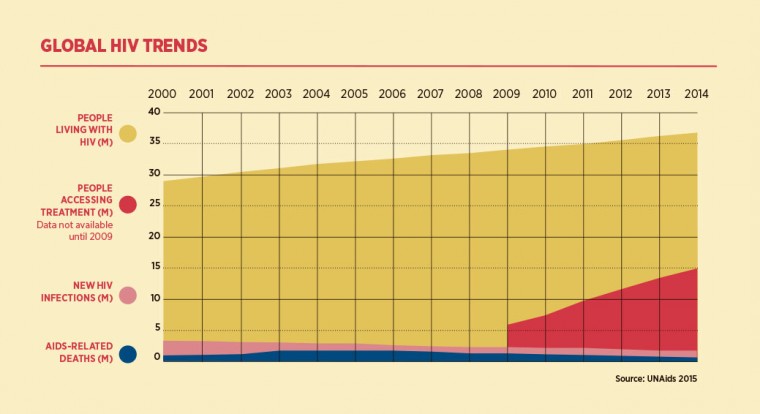

These drugs have played a crucial role in dramatically reducing the number of people who are infected with HIV to about two million a year, as well as allowing those with the virus to stay alive. As a result, about 37 million people globally are now living with HIV – two thirds in sub-Saharan Africa where half the new infections occurred in 2014.

Although some 15 million are receiving treatment, this means almost 60 per cent of people with HIV do not and as a result 1.2 million people died of Aids-related illnesses last year.

A long way to go

It is little wonder then that UNAids warns that the global Aids epidemic is far from over. The United Nations umbrella body for HIV/Aids has just published its new five-year strategy that has a seemingly ambitious goal – to end the epidemic as a public health threat by 2030.

Michel Sidibé, executive director of UNAids, says that over the next five years the aim is to reduce the number of new infections by 90 per cent compared with the rate in 2010, as well as ensuring that 90 per cent of those with HIV have suppressed viral loads. “We are optimistic in the sense that given the tools that exist today, it is possible to reduce very drastically all kinds of new infections and therefore end the Aids epidemic. But it will require a lot of additional effort,” he says.

Although some 15 million are receiving treatment, this means almost 60 per cent of people with HIV do not and as a result 1.2 million people died of Aids-related illnesses last year

The agency has adopted a fast-track approach that involves more effort to combat the spread of the virus as well as using better prevention techniques. “It is essential that acceleration happens because if things stall we will not be on track towards ending the Aids epidemic,” says Mr Sidibé.

One of the targets of the organisation’s previous five-year plan – making treatment available to 15 million people with HIV – was reached almost a year early. The UNAids chief adds that there has also been a “quite remarkable” reduction in the number of transmissions from mother to child, as well as an increase in the rate of voluntary male circumcision.

HIV funding

Ending the epidemic in the space of 15 years is going to require more money. The total funding for HIV globally is about $22 billion (£14.5 billion) a year, but UNAids believes this figure needs to increase to about $31 billion a year by 2020.

However, some organisations fear that HIV/Aids is in danger of falling off the aid agenda in Africa and elsewhere. Shaun Mellors, assistant director for Africa at the Aids Alliance says: “Partly it’s been overtaken by other priorities such as the refugee crisis. People also view HIV as being under control now that more and more people are on treatment and living longer. But we can see in Africa and other places that there’s still so much work to be done.”

Governments, the United States and Britain in particular, as well as philanthropic organisations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, provide a substantial amount of funding for HIV programmes in Africa. But some African governments have been increasing the amount they spend, with countries such as Kenya, Zambia and South Africa recording significant rises in recent years – more than $1 billion a year by the South Africans.

“For a long time South Africa suffered from political issues around recognition of HIV as the cause of Aids, but today it has the largest treatment programme and invests the most in its Aids response from its own resources,” says Mr Sidibé. He also commends Ethiopia and Rwanda.

While the HIV problem is still most acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where it affects the general population, countries such as Brazil, China and Russia have been combating outbreaks among specific groups, such as gay men, sex workers and their clients, and intravenous drug users. These groups can be up to 33 times more likely to have HIV than the general population, says Mr Mellors.

HIV treatment and prevention

Many obstacles remain to providing treatment and prevention for these groups in some countries. For example, drug users in Russia are criminalised and often jailed, and have very little access to syringe exchanges; sharing needles is a prime way of spreading the virus. “Where politics tries to interfere with science, it completely impacts on people’s lives,” he says.

Homosexuality, sex work and drug use remain criminal in almost all African countries, with South Africa an exception for homosexuality. But Mr Mellors adds: “We are beginning to see a change in how society understands and perceives the needs of these key populations in Africa.”

There is also a growing awareness that dealing with HIV/Aids in isolation to other health issues is no longer the best approach. Kelly Imathiu, who has worked for health and human rights groups in Africa and the US, including the Hivos Foundation, says African countries are adopting a more unified approach to public health. “Even the World Health Organization is asking other NGOs not to have unilateral funding streams for HIV/Aids, but to integrate them with all the other health-related issues,” he says.

If the UN’s targets for slashing the number of HIV infections and ensuring most people with the virus get treatment, Mr Imathiu says that social and legal issues must also be addressed. “It has to be an all-round outlook – all the factors that contribute to the spread of HIV need to be looked at,” he argues. “As long as there are laws that restrict people from fully realising themselves sexually, HIV is not going to end by 2030.”

Even in developed countries, infection rates continue to rise, particularly among certain at-risk groups. There were 6,151 people diagnosed with HIV in England last year, 119 more than in 2013, according to Public Health England. More than half (3,360) were among men who have sex with men, and that total was 90 higher than the previous year and 670 more than in 2005.

There are mounting calls for the NHS to offer PrEP – pre-exposure prophylaxis – which prevents HIV infection to at-risk groups. The treatment is expensive, but health campaigners point out that preventing an infection is far cheaper than providing antiretroviral drugs for decades, an argument that some US health insurers now agree with.

Mr Mellors at the Aids Alliance says PrEP should be readily available in the same way as condoms, needle exchanges and voluntary male circumcision, which has been shown to reduce infection rates in Africa. “Prevention has to come back on the agenda. There’s no reason why people should still be getting infected in 2015,” he says. “We need to ensure that people have access to an entire arsenal of prevention methods – so we put the person at the centre and not just see it as a medicalised condition.”

A long way to go