Less than a decade ago, a disturbing public health report discovered that scanners needed to diagnose stroke victims were kept under lock and key after office hours. An antiquated service also saw the technology positioned away from Accident and Emergency departments making it difficult for doctors to confirm their diagnosis.

Only 58 per cent of patients were given a scan within 24 hours, while at the Princess of Wales Hospital in Grimsby, the report noted, the average weekday waiting time for scanning results stretched to 48 hours – and stroke is a condition that waits for no man or woman.

The historical landscape of stroke goes some way to explain the lethal deficiencies in the service. The word stroke only came into common medical use in the 1960s, replacing the term apoplexy – from a Greek derivation meaning thunder struck – to describe what seemed to be a sudden and random affliction.

Rehabilitation from stroke was not regularly featured in medical textbooks until the late-1950s, according to the 1997 Age and Ageing report, as understanding of what was then identified as a problem of internal bleeding was still playing catch-up.

For the full infographic see here

Stroke services in England were officially graded as “poor” by the National Audit Office (NAO) in 2005, and a mammoth task of recalibrating public awareness, facilities, staff and delivery was instigated.

The campaign’s success is one of the NHS’s towering achievements – death rates have been almost halved in a decade – but clinicians are still fearful that life-saving and affirming treatments are not getting to patients. Also fresh government strategies could unpick the hard-earned progress.

UK far from word-class status

At the same time, figures from the World Health Organization show the UK still lags behind other, poorer nations in crucial aspects of morbidity and mortality.

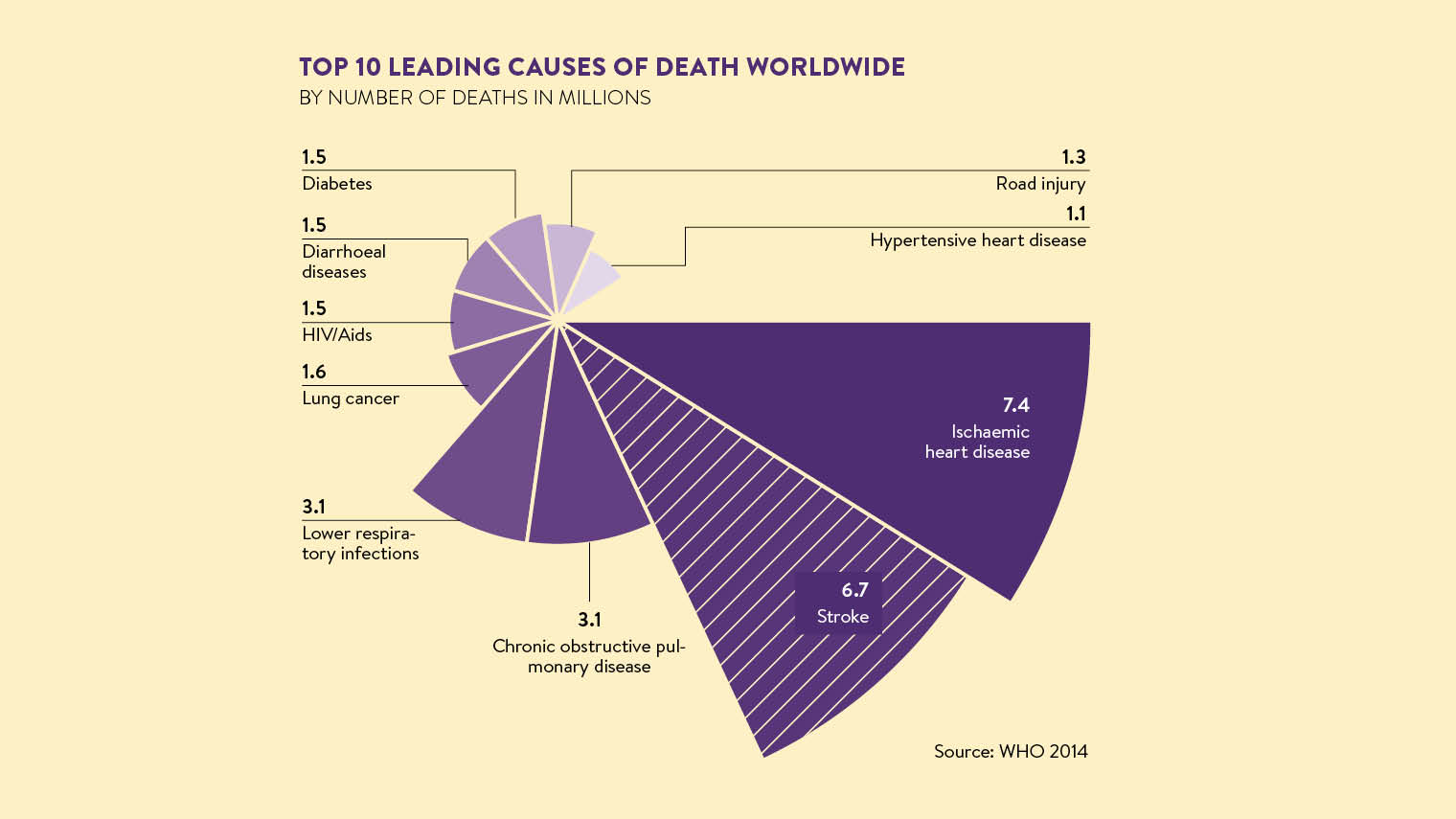

Its Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke records 15 million strokes globally every year, which leave five million dead and five million with permanent disability. The UK is positioned in the 10,000 to 99,999 bracket, denoting a death rate higher than Scandinavia, Belgium, Switzerland, Slovenia, Croatia, and some Arab and African nations.

Some of the disparity can be explained by different national reporting methods, but the emerging consensus is that the UK’s stroke services still need to improve before it can attain world-class status across the treatment disciplines.

The government’s response to the NAO 2005 shock was to give stroke tier-1 importance and load it with financial incentives, while the Royal College of Physicians launched the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme to provide important annual route markers of services.

“Both were important because, if you don’t know where you are, it is very difficult to tell when you will reach your destination,” says senior stroke consultant Damian Jenkinson, whose unit at the Royal Bournemouth Hospital was one of the first in the country to offer clot-busting thrombolysis treatment around the clock, as well as pioneering telemedicine to make rapid treatment decisions.

“Major improvements have occurred since the National Audit Office declared that services were poor quality and poor value for money. They could see by looking at care elsewhere on the planet that investing in certain parts of the pathway, and getting people with acute stroke into each stroke unit really quickly was going to improve the care and be efficient, effective and cheaper.”

Services and performance were revitalised by setting up 28 stroke-specific networks, and the FAST – face, arms, speech, time – acronym public-awareness campaign to enable swift recognition of the early symptoms of stroke gained traction.

But many experts feel the impetus has stalled. “It has sort of gone off the boil politically,” says Dr Jenkinson, a former national clinical director for stroke, who now works at Dorset County Hospital. “We are getting towards the end of the ten-year stroke strategy and lots of other strategies have landed on commissioners’ desks in the meantime. There is a feeling in the stroke community that the emphasis has waned.

“The Stroke Association is challenging the government to give the strategy a refresh and have a new era in stroke. It is a major challenge to finish off this work, but it feels, at shop-floor level, like there is a move to create more generic units where stroke victims will be treated alongside hip fractures and pneumonia patients.”

The contributory factors for stroke are similar to heart attacks, namely smoking, hypertension, atrial fibrillation and lifestyle-induced conditions such as obesity and diabetes. Drug therapies play a huge part in treatment with new ranges of anti-coagulants controlling blood flow and minimising the risk of a blockage to a cerebral artery.

Thrombectomy – a new technique

But a significant blot on the nation’s stroke service copybook is in the patchy use of recent developments in mechanical thrombectomy where a catheter is inserted, normally via the groin, to guide a stent to the site of a clot where it can be grabbed and removed quickly to restore blood flow to the brain.

Sanjeev Nayak, a consultant neuroradiologist at University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, in Stoke, who has pioneered the technique since 2009, believes thrombectomy can be performed on up to 15,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke a year, saving lives and reducing the level of disability for stroke survivors.

“The main concern is about the infrastructure – and the UK is way behind Europe and the United States when it comes to mechanical thrombectomy,” he says. “Despite the clinical evidence, less than 500 patients are treated annually within the UK with mechanical thrombectomy, when there are at least 8,000 to 15,000 eligible patients per year, which in my opinion is scandalous. This is due to lack of infrastructure and funding issues.

“In contrast, some 9,000 patients are treated in Germany. Developing the infrastructure with appropriate funding to deliver such a service in the UK should be a priority.”

His case list includes some startling results including a pregnant 27-year-old who was admitted in March with paralysis down the right side, and both her and the baby’s future in the balance. Dr Nayak was able to remove the clot in a 15-minute procedure and the woman walked from the hospital with no ill-effects and the pregnancy still viable.

It is almost as if stroke has had its day and the spotlight has switched to other areas such as cancer or dementia

Post-acute care is a key area where services need to improve through the early supported discharge scheme that provides rehabilitation at home for up to six weeks. Government figures show 25 per cent of clinical commissioning groups do not provide this.

“There is still a feeling that people get abandoned and there aren’t enough community support teams,” adds Dr Jenkinson. “We managed to reorganise care delivery in 170 hospitals, but it is proving harder to deal with the 90,000 patients discharged after stroke every year. Follow-up is a challenge and only a third of them go for their six-month check-up.”

Marion Walker, professor in stroke rehabilitation at the University of Nottingham, concludes: “It is almost as if stroke has had its day and the spotlight has switched to other areas such as cancer or dementia. However, the stark figures tell the story: this is a condition with high morbidity and mortality. We still haven’t cracked it and there is a gathering realisation of this and the need to bring the spotlight back on to stroke.

“There is life after stroke. It may be different, but it can be a very good life. People can still enjoy their family, friends, hobbies and get back to work. We have made huge strides in the last couple of decades and it has been a privilege to be a part of that, but there is still much to do.”

UK far from word-class status