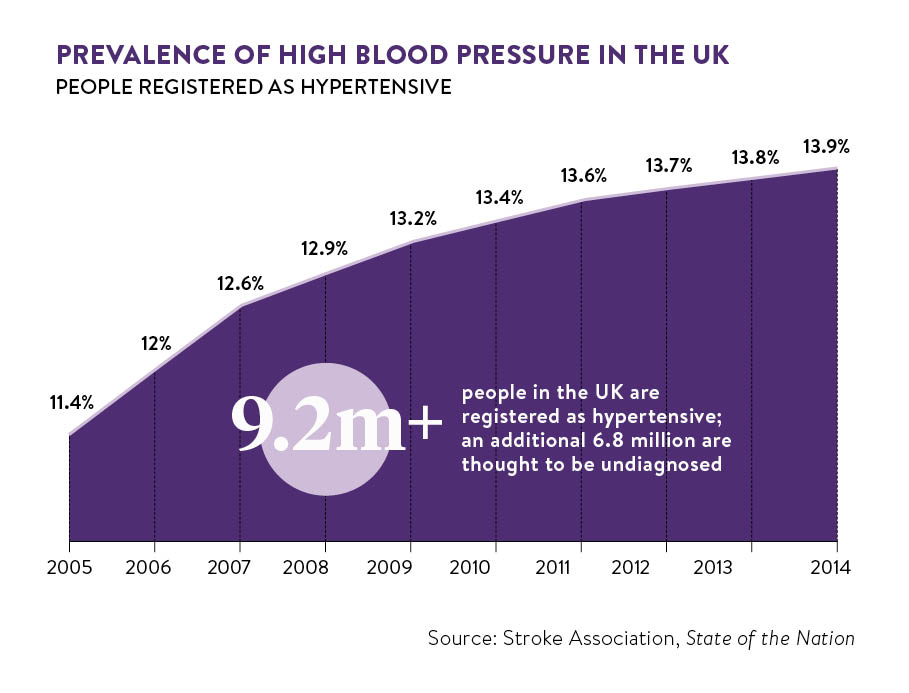

The key to reducing the frighteningly high incidence of stroke is taking control of the modifiable risk factors for the condition. And number one of these factors is high blood pressure or hypertension, which is a contributing cause in more than 50 per cent of strokes, according to the Stroke Association’s State of the Nation: stroke statistics report.

High blood pressure

The NHS says that ideally blood pressure should be below 120 over 80. Readings above 140 over 90 are considered hypertension. This puts strain on blood vessels, increasing the likelihood of strokes.

High blood pressure is by far the most important risk factor for stroke

Gareth Beevers, professor of medicine at the University of Birmingham and a trustee of Blood Pressure UK, says: “High blood pressure is by far the most important risk factor for stroke. In fact, when antihypertensive drugs became widely available in the 1960s, strokes were substantially reduced.”

In a review of 14 clinical trials involving a total of 370,000 people with high blood pressure, antihypertensive drugs such as beta-blockers (heart rate lowering medications) and diuretics (water pills) reduced strokes by 35 to 40 per cent.

Other risk factors for stroke

However, other factors are at play. Obesity, diabetes, high blood cholesterol, lack of exercise, smoking and excessive alcohol consumption all increase the chances of having a stroke. And these are greater for individuals with atrial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat) and people who have a family history of stroke, or are of south-Asian or African-Caribbean background.

As for increasing age, it’s worth noting that, while strokes are more likely among the elderly, one in four affect people younger than 65, according to the Stroke Association.

This plethora of risk factors means blood pressure shouldn’t be considered in isolation, but in the context of other patient characteristics, explains Dr Nicholas Summerton, a GP in East Yorkshire and former clinical adviser in primary care diagnostics to the Department of Health.

“A high reading matters more if, for example, you have diabetes or are a smoker. And a normal reading doesn’t necessarily mean you are problem free. It depends on your overall stroke risk,” he says.

Promoting and supporting prevention

Doctors can calculate a person’s stroke risk using a computerised tool (QRISK2) recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which provides national guidance on disease prevention and treatment.

This enables timely, personalised prevention. And prevention can save lives. In a report on hypertension, Public Health England says: “In ten years, 45,000 years of life could be saved, and £850 million not spent on related health and social care, if we achieved a reduction in the average population blood pressure.”

[embed_related]

But, achieving this goal requires a collaborative effort. On one hand, government and healthcare commissioners and providers must promote and support prevention. There are examples, such as the Department of Health’s Change4Life campaign, which encourages people to eat healthy and exercise more, and the NHS Health Check, a mid-life MOT offered to everyone aged 40 to 74. On the other hand, individuals must be willing to embrace prevention.

The good news is there are effective ways of integrating prevention in everyday life. Lucy Wilkinson, senior cardiac nurse at the British Heart Foundation, recommends “reducing salt intake to less than six grams per day, as this is directly linked to hypertension; aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week; and losing excessive weight”.

She says: “Avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption is also important. New guidance advises men and women to drink no more than 14 units of alcohol a week, and to have at least two or three alcohol-free days.”

Regular blood pressure monitoring

People should also have regular blood pressure checks. This is key to the early detection and treatment of hypertension, for the condition develops silently over many years, before the first symptoms become obvious.

Ms Wilkinson points out: “Nearly 30 per cent of adults in the UK have high blood pressure, but about half – around seven million people – are not receiving treatment because they don’t know they have the condition.”

Professor Beevers adds: “Every adult should have their blood pressure checked every five years or every six to twelve months if their blood pressure is borderline. The current recommendation is that higher-than-normal blood pressure should be brought below 140 over 90. But the general consensus is that interventions should be more aggressive and aim for readings below 120 over 80.”

Pippa Tyrrell, professor of stroke medicine at the University of Manchester, agrees and highlights the importance of monitoring approaches that can help with this, such as ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, whereby patients are fitted with an electronic device that measures their blood pressure throughout the day as they move around, and self-monitoring at home.

“They provide a large amount of data from readings taken in the patient’s own environment, helping with diagnosis and treatment decisions,” says Professor Tyrrell. Plus, evidence suggests that home self-monitoring, which a survey by the University of Birmingham estimates is already used by about 30 per cent of UK hypertensive patients, may improve health outcomes.

In a study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association, by an Oxford University team headed by Professor Richard McManus, self-monitoring led to greater blood pressure reductions than readings regularly taken by a doctor.

“Wearable technology can also help with certain risk factors,” says Dr Summerton. “For example, pulse monitors can detect heartbeat irregularities due to atrial fibrillation, which is associated with a five-fold increased risk of stroke. And fitness bands seem to encourage people to exercise more. But the evidence supporting wearables’ efficacy is limited.”

So there really are effective ways to control high blood pressure, address other risk factors and, ultimately, reduce the likelihood of a stroke. And these same measures can help those who have already had one. Therefore, the majority of strokes shouldn’t occur. As Professor Beevers concludes: “They should be almost a thing of the past.”

What is stroke?

A stroke is when the blood flow to part of the brain is cut off or reduced. It is also known as a “brain attack”.

When it happens, brain cells no longer get the nutrients and oxygen they need to function and begin to die. This can cause lasting damage to the functions or parts of the body the cells control. For example, a stroke may result in difficulties talking, swallowing, moving one arm or walking.

Two types of stroke

There are two main types of stroke: ischaemic stroke; and haemorrhagic stroke.

Ischaemic strokes are the most common, accounting for about 85 per cent of cases, according to the Stroke Association’s State of the Nation report. They occur when a blood vessel that supplies the brain becomes blocked. This can happen because of a blood clot that forms in the brain (thrombotic stroke), or because of a blood clot or air bubble that forms around the body and travels up to the brain (embolic stroke). Ischaemic strokes can also be caused by a fatty material, called plaque, which builds up inside blood vessels reducing blood flow. This is known as atherosclerosis.

Haemorrhagic strokes occur when blood vessels in the brain leak or burst causing bleeding. In this case, brain cells die because of the build-up of pressure from the bleeding. Haemorrhagic strokes can happen inside the brain (intracerebral haemorrhage) or in the space between the brain and the tissue that protects it (subarachnoid haemorrhage). They are rarer, but generally more serious, than ischaemic strokes.

High blood pressure