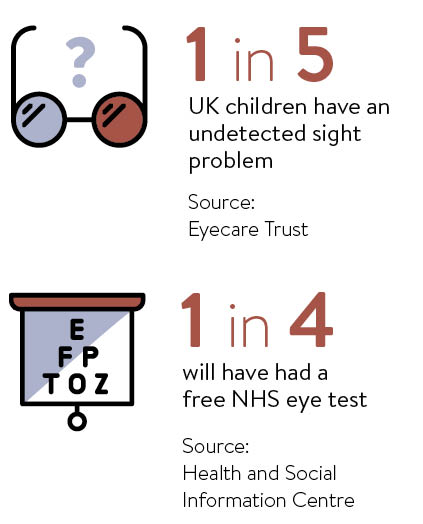

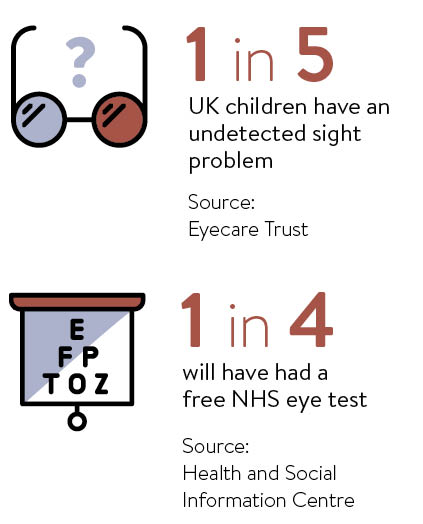

Walk into any classroom in the UK and you would find that up to one in five pupils had an undetected sight problem, according to charity the Eyecare Trust.

Although NHS data shows we are well drilled on when to take our child to the doctor or the dentist, we may not be as confident about when children need an eye test.

Figures from the Health and Social Care Information Centre show that although nine in ten children are vaccinated and seven in ten regularly see a dentist, only around one in four children will have had a free NHS eye test.

Anna Horwood, an orthoptist and principal research fellow at the University of Reading, says: “A test in childhood is important because if reduced vision is not picked up while children’s vision is still in a period of developmental plasticity – called the “critical period” - vision may be permanently reduced even if the right glasses are given later.”

New evidence suggests many areas of the country no longer offer vision screening led by an orthoptist for children in reception class

But when should an eye test take place? NHS staff will assess a child’s eyes at birth and six weeks. The next routine assessment should be at school when children are four or five.

At this age there is still time for conditions such as lazy eye to be treated before its effects become irreversible. Children who need glasses can also be identified before their vision affects school life.

But new evidence suggests that despite being recommended by both the NHS and the UK National Screening Committee, many areas of the country no longer offer vision screening led by an orthoptist for children in reception class.

But new evidence suggests that despite being recommended by both the NHS and the UK National Screening Committee, many areas of the country no longer offer vision screening led by an orthoptist for children in reception class.

Anita McCallum, from the British and Irish Orthoptic Society (BIOS), says: “Our research suggests that there is a void in many areas providing the tests at all.”

Freedom of information requests by the BIOS to all 151 local authorities responsible for the service found only 55 per cent of councils were commissioning orthoptist-led screening in schools and some said they may soon withdraw it. Areas that didn’t screen children said they have no plans to restart.

Lazy eye treatment

If school screening is not offered, parents are advised to go to an optician for a free NHS eye test instead.

This is because lazy eye or amblyopia, which affects one in fifty children, needs to be treated as soon as possible. Once diagnosed, it can be cured using an eye patch, but this window for treatment may close when a child reaches the age of seven.

At this point, the central vision in the weaker eye may never develop to normal levels.

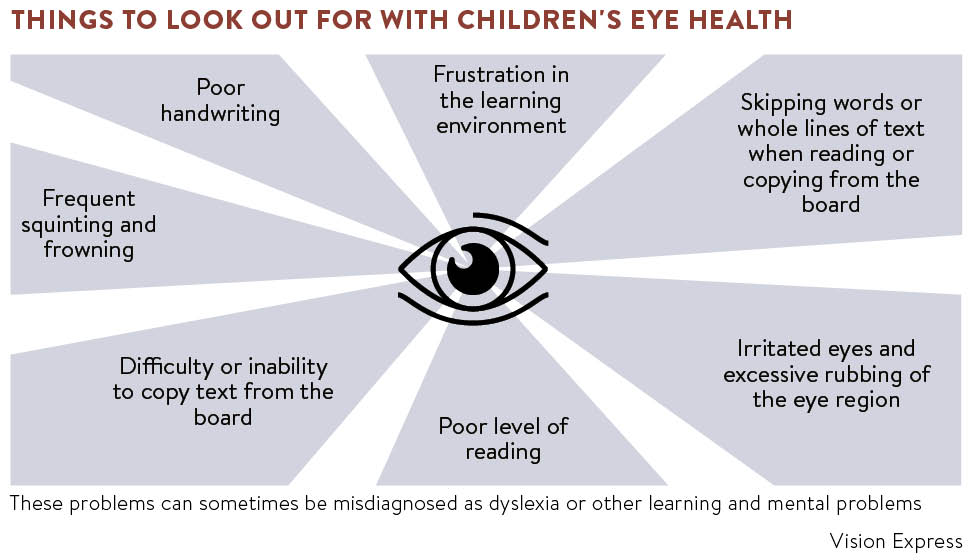

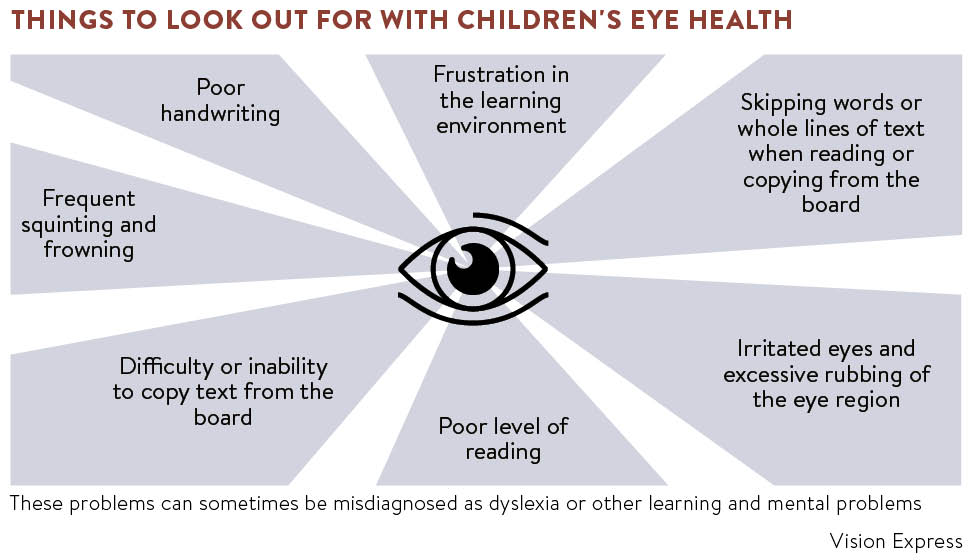

Daniel Hardiman-McCartney, a clinical adviser at the College of Optometrists, says parents should also go to the optician if they notice their child is sitting close to the TV, complaining of headaches or suffering from poor concentration. This may indicate a child is short-sighted, known as myopia.

“It is also important to get your child tested if one parent is short-sighted,” he says. “This makes it more likely for the child to be short-sighted. If both parents are short-sighted, the likelihood increases further.”

He says that in the 1960s just 7.2 per cent of British children under the age of 13 were short-sighted, but today it is around 16.4 per cent.

Experts are not certain why the figure is increasing, but they do know it is linked to the amount of time children now spend indoors.

Although lazy eye and myopia are the most common conditions affecting children, occasionally eye tests can detect serious disease. For example, retinoblastoma is a cancer of the eye that affects around 50 children a year, but is successfully treated if spotted early enough.

Early diagnosis

Visual impairment – when a child’s sight cannot be corrected using glasses – can also be discovered during screening or eye tests, although most of these cases are picked up when a child is still very small and treated by a hospital ophthalmologist.

Dolores Conroy, director of research at the charity Fight for Sight, says: “There is a lot that can be done to help children who are visually impaired; they can receive special support at school and technology such as iPads can also help.”

Earlier this year, a study showed that even children with more common, treatable eye problems benefit from an early diagnosis.

A study of 6,000 children in Bradford, published in the journal BMJ Open, found that every one line reduction in vision during screening was linked to a 1.7 point drop in literacy scores at the age of four and five.

Fight for Sight is now funding Dr Horwood to research whether another common sight problem – poor near-focus – could also affect school performance.

According to the NHS Choices website, children should have their sight tested once every two years if the child has normal vision.

The College of Optometrists, which represent opticians, say they believe it should be once a year until a child reaches their teens and then once every other year if they have good sight.

Mr Hardiman-McCartney points out tests take only 15 minutes, are free and children do not need to be able to read the alphabet. He says there has also been an important shift in attitudes to children wearing glasses.

“The Harry Potter effect has been huge. Parents may worry about their children needing glasses, but I often find children are disappointed when they discover they don’t need a pair,” he says.

Dr Conroy concludes: “Unlike adults, children may not realise they can’t see well, they just think that is how everyone else sees the world and they simply move further towards the front of the class to see.

“We know we can prevent sight loss. Of the 1.8 million adults with it, half have reversible eye conditions such as refractive error and cataracts. It is important that looking after eye health starts at an early age as there is so much we can do to help.”

Lazy eye treatment