Around the world people are living longer. By 2020, for the first time in history, the number of people aged 60 and older will outnumber children younger than five years old, according to figures from the World Health Organization (WHO). By 2050, the worldwide over-60 population will have more than doubled to reach 2 billion, from 841 million today.

On the face of it, rising life expectancy sounds like pretty good news, but in fact it’s set to stretch healthcare systems beyond breaking point.

That’s because, after the age of about 50, a host of age-related illnesses start to appear. Many are chronic conditions, long-lasting illnesses that can be controlled but not cured and tend to worsen over time.

Managing illness

An example is type 2 diabetes, which most commonly develops in people over 40. In the UK, there are now 60 per cent more people living with this condition than there were a decade ago, according to figures recently released by charity Diabetes UK.

Another example is dementia. According to the WHO, the latest estimates indicate that the number of people living with this condition will rise from 44 million today to 135 million by 2050. Similar patterns are observed with arthritis, osteoporosis, cardiac disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Connected medical wearables and implants will collect data, check patients are taking their prescribed medicines and even administer drugs themselves

In other words, many of us can expect to live longer than previous generations, but those years won’t necessarily be happy or productive for us if we’re beset by illness and unable to access the medical care we need. Above all, these conditions require careful adherence to drug regimes and regular monitoring by doctors. But if these requirements can be met, many patients can continue to live independent lives at home and stay as healthy, active and as pain free as possible.

It’s a big opportunity, say healthcare experts, for smart, connected medical wearables and implants. These devices, worn by patients and bristling with sensors, will collect data on glucose levels, blood pressure, blood oxygen levels, sleep patterns and coagulation rates, for example. They’ll be able to check that patients are taking their prescribed medicines, at the right times of day and in the right quantities. They’ll even, in some cases, be able to administer drugs themselves.

And all that information can be fed back to the patient’s physician, creating an ongoing record of how an individual’s condition is progressing and alerting them if it is deteriorating, and a face-to-face consultation or even a hospital stay may be required.

Wearables for patients

But it’s not just doctors who will benefit from this data. It will also enable the patients themselves to take a more proactive role in managing their own condition, says Jeroen Tas, chief executive of the informatics solutions and services business at Philips Healthcare, a subsidiary of the Dutch electronics giant.

“An informed patient is a more confident patient,” he says. “They’re in control of their illness, responsive to their own symptoms and able to have a better experience of their condition,” he says.

In October 2014, Philips announced a new wearable device prototype in partnership with the Radboud University Medical Centre in the Netherlands. It’s designed to support patients with COPD, an illness characterised by persistent blockage of airflow to and from the lungs, leading to shortness of breath and thought to affect some 64 million people worldwide, according to WHO figures.

The device is worn as a smart adhesive patch and collects data on activity levels, respiratory function, and heart rhythm and rate. That data is then sent, via the cloud, to the Philips HealthSuite Digital Platform, where it is shared with two apps, eCareCompanion (for the patient themselves) and eCareCoordinator (for the medical staff who support them).

Wearables could equally relieve patients of some of the burden of managing their conditions; the need to remember to take their drugs, for example. Last November, US syringe manufacturer Unilife bagged an exclusive, 15-year deal to supply French pharmaceutical company Sanofi with its wearable injector devices, which are worn under clothes and deliver drugs in the recommended dose through the subcutaneous fat of the patient’s abdomen.

According to an independent market research report published by Roots Analysis in September 2014, the market for this kind of wearable injector will generate up to $8 billion in sales by 2025, with 14 disease areas already identified as suitable targets for these devices.

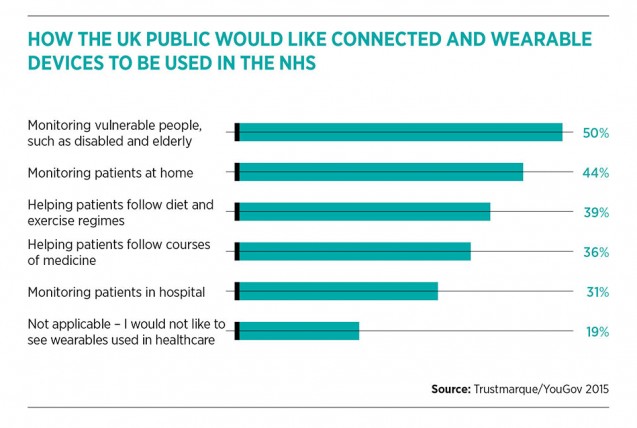

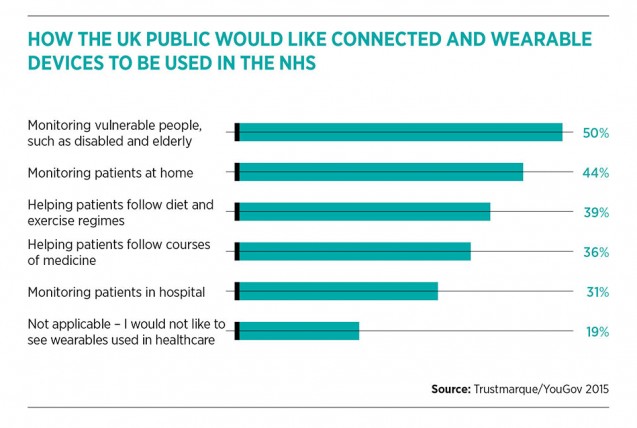

Patients seem open to such innovation. In a recent survey of more than 2,000 UK adults conducted by pollsters YouGov on behalf of Trustmarque, a technology services company, 81 per cent of respondents said they welcomed the idea of wearable devices in healthcare.

Challenges

There may still be hurdles along the way for healthcare wearables, however. Healthcare innovations must first gain the acceptance of providers in carefully regulated markets and undergo extensive clinical trials before they can be launched on any scale, says Frazer Bennett, a technology expert at PA Consulting.

He says many fall victim along the way to a condition he jokingly calls “pilotitis”, a failure to make it through lengthy pilots and into wide-scale implementation.

“This tends to happen for two reasons. One of them is a commercial reason – devices simply lack the backing of a robust business case for moving them out of the lab and into the clinic. The second is a lack of understanding of patient need from the outset,” says Mr Bennett.

With PA Consulting’s own invention, a wearable, internet-connected patch the size of a 10p piece, he believes the firm can side-step the piloting problem. It has kept its patch as simple as possible and as cheap to manufacture as 50 US cents per patch, he says, and is carefully targeting a handful of specific use cases, the measurement of particular symptoms, for example, or monitoring whether a patient takes a specific drug.

But above all, PA Consulting’s patch has been designed with patient convenience in mind. “It’s small, no bigger than a plaster, so it can be worn unobtrusively. It doesn’t require the patient to change their behaviour. And it allows them to get on with their lives, confident that their health is being monitored,” he says.

Managing illness