Hadalat camp, if it can be called a camp, stands on the Syrian- Jordanian border, a desolate place where the no man’s land divides a war-torn country from its more stable neighbour. Two small sand-hills on either side of a dip – the berm – divide those who’ve escaped the war zone from those who can only dream of it. Roughly 6,000 people live in the informal collection of tents at Hadalat, where the landscape stretches out into nothingness in every direction.

There are only six toilets on the Jordanian side of the berm at Hadalat, to serve thousands of people, and none on the “camp” side. There is no running water and no evidence of regular food deliveries – though NGOs said some food has made it through; nor are there formal schools, or any kind of basic sanitation. The camp is makeshift, with no structure or management – which in turn means no security.

Unbelievably, the residents of Hadalat are the lucky ones: accessible by road, they were receiving regular aid and most within the camp were processed by the Jordanian authorities within about two months of arrival. Most have arrived from areas of southern Syria, which are controlled by more moderate rebel groups, ensuring that they are given a more fulsome welcome by a Jordanian government that has become more skittish about security as the violence next door has spilled over.

Two hours up the road at Rukban, an even larger camp with 60,000 refugees, the situation is even worse.

Banished to the no-man’s-land side of the berm, it is a camp in name only. The collection of structures is positioned arbitrarily in the arid, desert landscape. A few fortunate residents have small tents provided by aid agencies; most live in loosely constructed shelters, patched together from sticks, blankets and pieces of sheeting.

A handful of wheelbarrows, used to carry the residents’ worldly belongings, double as toys for the children. Most refugee camps bustle with life; this one does not, as if the pause button has been pushed on its residents’ lives while they wait out their stay here in purgatory.

When it rains, residents are lashed by the elements and the unpaved access road becomes impassable, meaning those staying there frequently go days without water or food. Médecins Sans Frontières says the most common ailments among refugees are skin diseases, diarrhoea, and malnutrition: all would be easily treatable ailments with the proper care and supplies.

The desperation at Rukban is the direct consequence of the Jordanian government’s shift towards a policy that prioritises security over its humanitarian obligations. The country has taken in around 1.4 million refugees from Syria – of whom only one fifth are in formal camps – straining its public services and stretching its capacity for generosity to the limit. However, Jordan is also involved in the regional conflagration that has resulted in, and been fuelled by, the rise of the so-called Islamic State, making it a target for terrorist groups and insurgents. In that environment, it has hardened both its attitudes and its borders, leaving thousands of people trapped on the fringes of the brutality of the Syrian civil war.

Jordan’s approach is far from a unique concern. Worldwide, nations beset by the twin challenges of transnational terrorism and the migration crisis are equating the two, using national security arguments to deny access to genuine refugees for fear of admitting dangerous individuals. In the West, European nationalists and anti-migration parties have explicitly linked terrorism with refugees; in the US, presidential candidate Donald Trump has said that those fleeing conflict could be ‘Trojan Horses’ for IS.

In Jordan, the change in attitudes seemed to pivot on a two dramatic events, one of which occurred here on the border.

Crowds mass at the border crossing - KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/Getty Images

The border closes

One spring day in Hadalat, 300 Syrians were allowed to cross into Jordan. After a group that gathered sang a surreal but rousing tribute to Jordanian ruler, King Abdullah II, the lucky ones were chosen from a list and sent by the camp elder to fetch their things.

Aided by military personnel, they were helped over the berm to be searched, before being loaded on to trucks that would take them to a reception centre with food, and further security checks and health screenings, before a final journey to the Azraq refugee camp south of the capital, Amman. Among them were two young boys who had travelled alone to the berm: they said that their parents had been killed by a Russian airstrike.

Umm Ahmad and her family were the last to be processed for the day. As she ran toward the line for the trucks that had come to take them to be processed and then on to the camps, she was first joyful, then stood weeping, overcome with a mix of emotions.

Having come from Homs, she had her husband and four children with her. The youngest, just six months old, “was born underground”, Umm Ahmad said, wiping tears from her eyes as she grapples with the mix of emotions the beginning of her new life brought up.

While pregnant with him, “I lost his brother, he had an infection and I couldn’t get the medicine.” They waited to leave, hoping the war would end, for five years before finally giving up on that outcome, travelling for a month to reach the berm and waiting nearly two months to cross into Jordan. “We are safe now, god willing,” she said as she assembled her family and scrambled onto a truck.

Not long afterwards, a suicide bomber detonated not far from the camp, killing six Jordanian soldiers and wounding 14 others. The attacker was believed to come from Syria, and the event accelerated the narrative that the camp’s residents represented a security threat. After that, no more groups like Umm Ahmad’s were allowed through.

Access was already limited before the attacks. Since then, conditions have deteriorated even further. The Jordanians shut access to the berm altogether, although they have recently allowed UNICEF to deliver water to the camps on the border and are in discussions with other NGOs about the possibility of reinstating food deliveries and access to medical care.

The insecurity at the camps has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Without order, NGOs have not been able to distribute supplies or cross the berm to engage with refugees in the informal camp. This means that supplies are hoarded and sold off on the black market.

The International Committee of the Red Cross and MSF have confirmed their concern for the people living along the berm. “These people – more than 50 per cent of whom are children – desperately need the immediate resumption of the provision of food, water and medical care. This cannot wait,” says Benoit De Gryse, MSF’s operations manager.

Those who come to Rukban are fleeing areas under the control of IS so are viewed as a higher security risk by the authorities, who assert that around a third of the camp’s population have no intention of entering Jordan, or actually have malevolent intentions if they do intend to enter. This assertion is impossible to verify and is disputed by NGO workers who have been to the area.

Security first

The Jordanian authorities control the area around both camps and the berm itself is a closed military area. The press is not welcome and the small number of NGOs with permission to work in the area are no longer allowed.

Like aid workers in Syria, they must balance the imperfect conditions here with the chance their access may be punitively reduced for speaking out, and the Syrians in need would see their aid cut. Those who have been there, or work there, admit in hushed tones in Amman that the conditions contravene every aspect of the humanitarian principles they attempt to uphold in their work.

“People fleeing war should be offered international protection and a safe place to relocate. Neither Syria nor the border are safe today,” says De Gryse. “This is a collective responsibility and a massive failure of the international community. This is not just Jordan’s responsibility. There are plenty of countries both in and outside of the region who should also step up to offer a safe place

for refugees.”

Jordan’s security-centric approach to what is, fundamentally, a humanitarian situation may seem extreme, but it is reflective of a global trend towards treating refugees as a threat. The UK’s most recent aid strategy, for instance, was published in November 2015 under the title, UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest, and the first of its four work-streams focuses on security. Only the last addresses more traditional aid and poverty reduction outcomes.

“States are increasingly putting an emphasis on national security, rather than protection, when considering refugee arrival policy and humanitarian action. While this shift of focus is not new and is not limited to the Middle East, it has arguably never been as pronounced as it is now, as we witness the large-scale secondary movement of so many Syrian refugees,” says Daryl Grisgraber, senior advocate at Refugees International.

Just as Europe initially welcomed refugees who arrived on its shores in spring 2015, before scrambling to contain them, Jordan has struggled to absorb flow of people out of Syria.

In the early stages of the crisis, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees tweeted images of refugees making their way across the desert to Jordan, freely roaming the area and being warmly greeted by aid workers upon arrival. As that trickle grew, the country opened the camp in Zaatari. Initially a tented camp, it is now a semi-permanent city of 90,000 people. Its main shopping street is a collection of creative small businesses selling goods from the outside, and some fashioned by artisan residents within it, jokingly named the “Shams-Élysées” after the famous boulevard in Paris and a historical name for Syria.

When Zaatari became full, a second large camp with space for 140,000 residents was opened in Azraq, south of Amman, in April 2014, though it is barren and unpopular with refugees.

The UN-run Zaatari camp for Syrian refugees, north-east of Amman - KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/Getty Images

As the number of Syrians arriving in the Kingdom continued to rise, Jordan’s approach to addressing their needs began to switch from purely humanitarian to a balance between aid and the security of its own citizens.

The country had a population of 6.5 million in 2013, estimated to be 9.5 million in December 2015, of which around 1.4 million were Syrian refugees, with 650,000 officially registered as such. A country with no significant natural resources and high public subsidies, the drain on even basic services – water, electricity, housing – risked destabilising the country. Official border crossings have closed and key trade routes dried up with both Iraq and Syria. Unemployment is rising, especially among Jordanian youth.

Fears that fighting between armed factions in Syria, alongside the arrival of millions of refugees, will lead to domestic unrest and alter Jordan’s national character are reinforced by the fact that such a spillover, resulting from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, did occur the 1960s and 70s. Those strains on the Kingdom then led to the “Black September” conflict with the Palestine Liberation Organisation and several thousand deaths during the reign of King Abdullah II’s father, Hussein.

A Jordanian soldier scans newly arrived Syrian refugees as they wait to cross the border - KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/Getty Images

Military escalation

If the bombing at Hadalat cemented the security-first policy in Jordan, the foundations were set 18 months before, when a video of Royal Jordanian Air Force pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh being burned alive was released in early 2015.

On December 24, 2014, al-Kasasbeh’s plane was downed over Raqqah while on a bombing mission as part of the coalition to defeat IS. The pilot’s capture was shown in mobile-phone footage released at the time. After being exploited for an “interview” in Dabiq magazine, it is believed he was murdered on January 3, 2015.

His death was shown in an especially brutal video in which he was caged and set on fire while conscious. The punishment was designed to reflect the “eye for an eye” aspect of Islamic law practiced by IS, his burned body was covered in rubble by a bulldozer after his death, in an attempt to replicate the impact of an airstrike.

The propaganda video, which was released only after convoluted, high-profile hostage negotiations to trade him and a kidnapped Japanese journalist, Kenji Goto – who was also eventually murdered – played out in public between IS and the Jordanian government, which may have been aware of the pilot’s death at the time. Both groups called the other’s bluff until the release of the grisly video, which was clearly aimed at threatening the Jordanians and making them “pay” for their involvement in the coalition airstrikes on IS.

The reaction in Jordan was one of anger and shock. Significant numbers of refugees from neighbouring Syria had already been let into the country. Proud of their military, many Jordanians felt the attack suggested a lack of security for the nation itself.

A Jordanian student holding a portrait of murdered pilot Maaz al-Kassasbeh sits in front of a giant poster showing Jordan’s King Abdullah II, during an anti-IS rally in Amman

The outcry put King Abdullah II in a difficult position: a military man himself, he immediately urged the importance of the fight against IS while also fearing that the group might try to replicate the sort of attacks that al- Qaeda in Iraq carried out in November 2005, when three hotels were bombed in Amman.

The murder pushed an increasingly security-focused policy toward one where that was the paramount objective, to the exclusion of all other considerations. To make an example, in February 2015 the Jordanian government executed two AQI members: Sajida Mubarak Atrous al-Rishawi, who took part – unsuccessfully – in the 2005 Amman attacks, as well as former Iraqi Army officer Ziad Khalaf al-Karbouly, who was arrested in Jordan in 2006 and charged with kidnapping and murder.

The same month, Jordan carried out a record number of airstrikes in Syria, though since last summer such actions seem to have tapered off – perhaps due to Russia’s direct intervention in the war. All of this was made easier by the support of Western countries in two key ways: the US’ support for securitisation of the border region and the EU’s recent trade deals with the country at the London donor conference earlier in the year.

Started in 2013, the Jordan Border Security Programme, a state-of-the-art system built by the US defence company Raytheon, stretches nearly 500km along the borders with Syria and Iraq. The $500 million (£340 million) system, which includes cameras, ground radars and a futuristic command-and-control centre, was principally funded by the US government.

Economic development

The security programmes on the borders create some hope that trade, which has been all but halted in the past few years, can resume. From tourism to agriculture, the border closures have hit across multiple economic sectors. Jordan’s position as a transit country along regional trade routes is under threat.

The economy, which had been growing rapidly up until the global financial crisis, has continued to expand at 2 to 3 per cent per year, but the massive increase in its population has swallowed up that growth.

Through heavy cultivation of donor assistance and a policy of keeping refugees at arm’s length in the border zone, Jordan has seemingly mitigated some of the pressures that other countries, such as Turkey, Lebanon and Iraq, are buckling under. But with the war showing no signs of ending soon and many of the refugees settling in for the long haul because it is not safe to go back home, how long Jordan can maintain this balance is uncertain. Jordan’s playing up of its ties to the West have been especially important for securing economic assistance and new trade deals. King Abdullah II has been especially successful in leveraging its refugee host status to secure money.

As Turkey negotiated visa-free access to the EU in exchange for a controversial refugee return deal, Jordan asked for – and received – loans for economic development, and new co-operation deals.

The EU is happy to back Jordan’s economy, hoping to keep the refugee problem contained in Syria’s neighbours, and mitigate the tension on their own borders. A deal, signed in July, grants Jordanian products made in several ‘special economic zones’ easier access into the EU – on the condition that factories must derive 15 per cent of their labour from within the country’s Syrian refugee population. It is a small step, but it does start to address one of the most critical problems that Jordan faces – how to turn the refugee population into an economic resource, rather than a burden.

King Abdullah II with German chancellor Angela Merkel at a meeting in June 2014

As David Schenker of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy says, this only goes so far before the long-run effects impact the country’s economic and social make-up: “history shows us that if refugees stay somewhere for more than ten years they never return, so they’re going to have to figure out a way to integrate these people into their economy as well, which will cause a lot of social dislocation.”

For Umm Ahmad and her family, these policies offer some hope for the short term. There is little chance they will be able to return home any time soon, and they need Jordan to attain some level of economic stability and growth to support them, and allow them to support themselves.

For those who remain on the berm, the focus on economic development and security, with humanitarian response a distant third, the situation looks far bleaker.

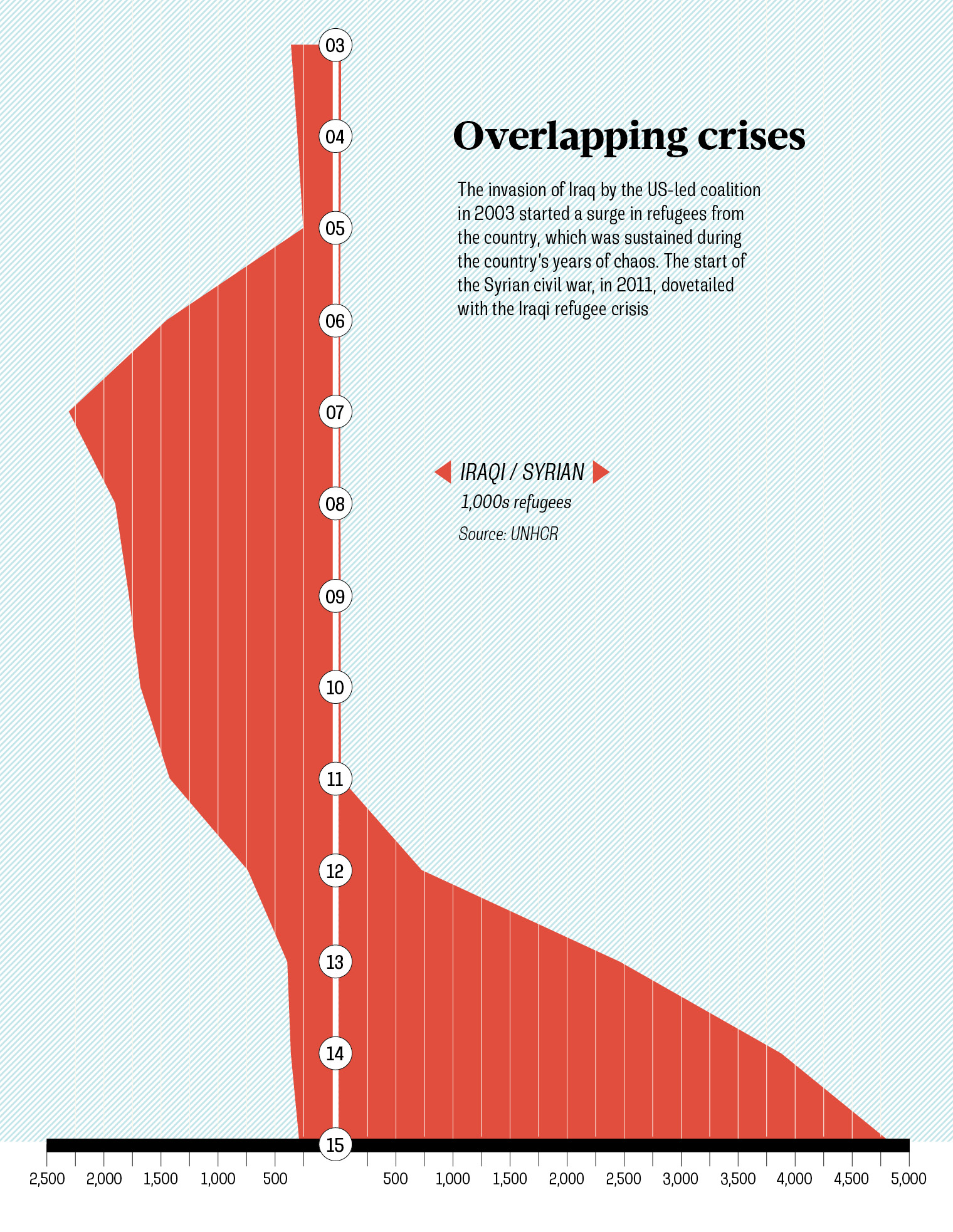

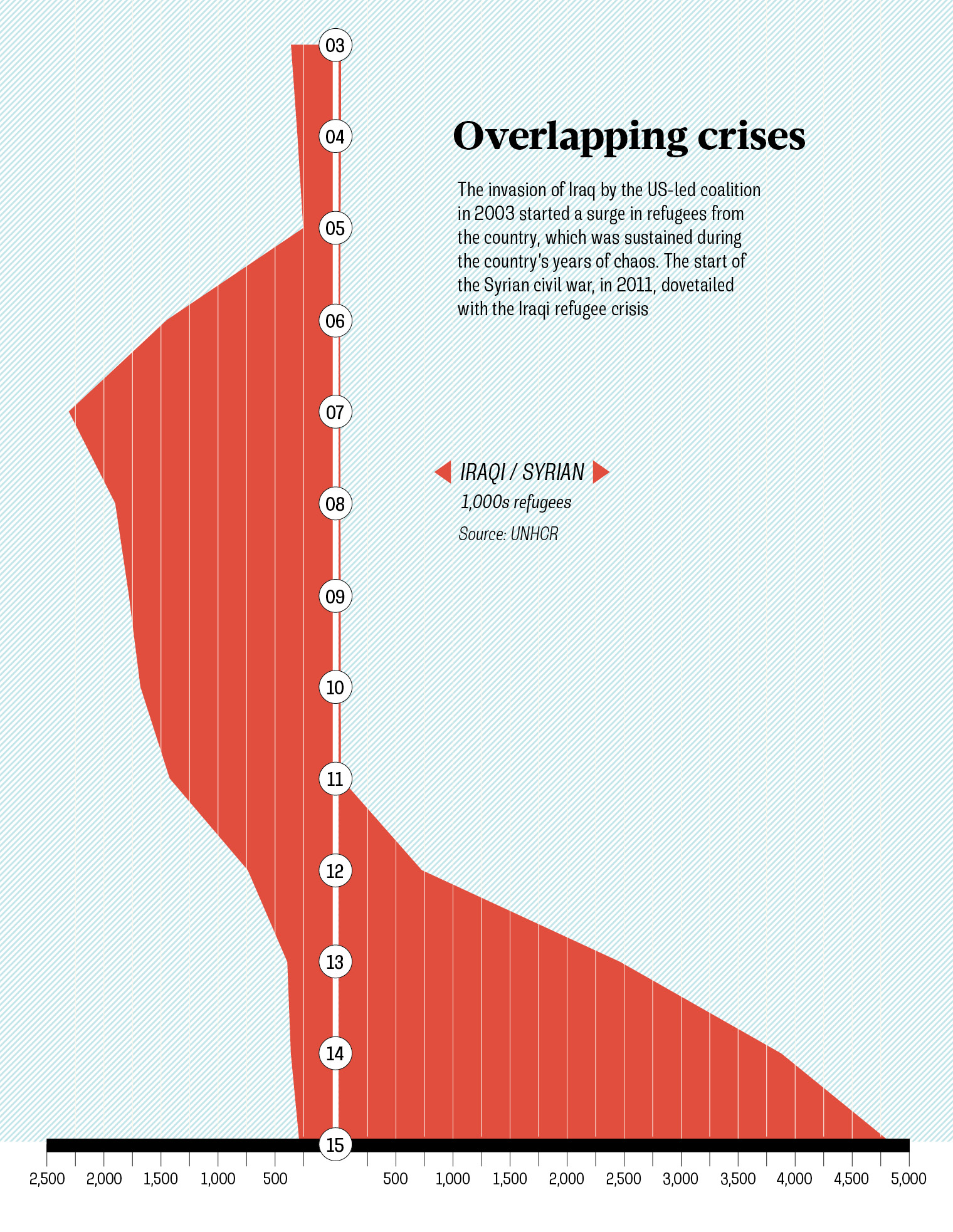

Timeline: Syria’s civil war

Since pro-democracy protests began in 2011, the Syrian state has all but disappeared into a conflagration of rebel groups and international proxies, with civilians often caught in the crossfire.

The border closes