More than five million additional workers now save in a workplace pension as a result of auto-enrolment, a number that could double by 2018 when the first round is complete for existing employers.

The auto-enrolment programme has been widely heralded a success, with opt-out rates well below expectations. Around 8 per cent have left their workplace schemes compared with predictions that 30 per cent would do so.

However, while millions who have never saved into a pension before are now saving on a regular basis, the sums involved fall far short of funding a comfortable retirement. The minimum contributions are determined by the government and are only 2 per cent of qualifying earnings, increasing to 5 per cent from October 2017 and 8 per cent from October 2018.

While opt-out rates are low, critically they relate to the current 2 per cent contribution of which employees pay just 1 per cent. By 2017, when the total contribution rises to 8 per cent, employees will be expected to make a 4 per cent contribution from their own pockets. What then happens to opt-out rates will determine the success of the project.

Saving struggles

For a person on average earnings, even an 8 per cent contribution will create a fund that still falls well short of the Pension Commission’s suggested pension income target of two-thirds of pre-retirement income, assuming a 3 per cent per annum real return on investment. In fact, it is only around half the 14 to 16 per cent actuaries calculate is required to reach this retirement-income level.

Furthermore, most people being auto-enrolled are over 22 with fewer years remaining to save and catching up is hard to do. While a median earner, who joins a workplace pension at the age of 22 and contributes continuously until state pension age needs total contributions of 11 per cent to have a two in three chance of adequate retirement income, for an employee in their 40s, the contributions required would be 26 per cent, according to the Pensions Policy Institute.

One way to raise contributions is auto-escalation, a scheme where employers increase member contributions annually by a set increment, commonly 1 per cent

In practice, the overall picture is even worse because people do not generally work consistently throughout their lives, but often experience periods of unemployment and, for women especially, periods of care-giving.

Neither are the contributions based on an entire salary, but only on so-called qualifying earnings, which are those that fall between a lower and upper earnings limit set by the government, which this tax year is between £5,824 and £42,385.

To be auto-enrolled at all, an individual’s earnings must exceed the lower earnings threshold, which for 2015-16 is £10,000, disenfranchising many women and low earners.

This situation will be improved by the new national living wage of £7.20 an hour that comes into effect in April 2016. This will ensure that all employees aged 22 and above, working over 20 hours a week, will qualify. In fact, around one million more individuals will be pulled into auto-enrolment because they will earn the living wage, so their wages will rise, but the trigger for enrolment will stay at £10,000 a year in real terms.

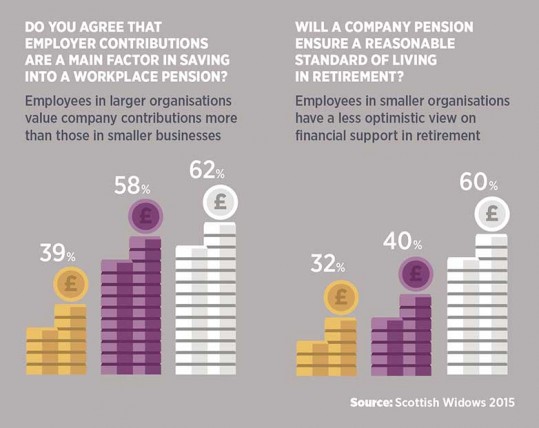

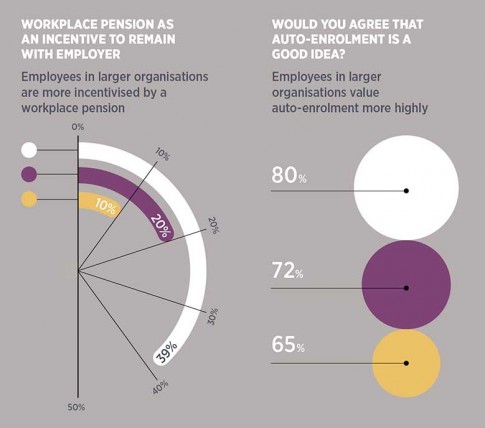

[infographic]

Auto-escalation

One way to raise contributions to levels that will create more meaningful pension savings is auto-escalation, a scheme where employers increase member contributions annually by a set increment, commonly 1 per cent. This is very popular in the United States where savers typically start paying 5 per cent into their retirement savings plan and build it up by 1 per cent every year. The idea is that employees will not feel the additional deduction too keenly if it is timed to coincide with a pay rise and the pension grows with more momentum owing to the compounding of the increased contributions.

Fidelity has examined its US books and discovered that 38 per cent of savings increases were a result of auto-escalation programmes and that for Generation Y workers auto-escalation accounted for half of all contribution increases. In the UK, a recent Association of Consulting Actuaries (ACA) survey found a quarter of employers support the concept, leading the association to suggest to the government that contributions should be increased by 1 per cent every two years after 2020 until they reach 16 per cent.

It is fairly certain that many millions of employees have no idea that the amounts they’re saving will not provide a decent income in retirement

“While much of the debate has dwelt on legitimate desires to drive down charges and to free up pension monies by way of the popular freedom and choice reforms, our survey points to the greater need, part of what we see as the next step strategy, that looks to a gradual, but essential increase in contributions,” says David Fairs, ACA chairman. “This is needed to ensure that many more retirees save sufficient amounts for both a comfortable retirement income and one where they have real choices to spend some of their accumulated savings as they approach or reach retirement.”

Very shortly, large employers, who led the initiative in October 2012, will start to auto-re-enrol their employees who previously opted out of the scheme, an obligation they must undertake every three years. Generally, unless these people have changed financial or family circumstances, they are likely to opt out again, but some may change their minds because of the new pension freedoms.

Older workers tend to opt out because they feel the scheme wouldn’t make a material difference to their retirement. In fact, 23 per cent of workers over 50 opt out compared with 7 per cent of those under 30 and 9 per cent of those aged 30 to 49. The introduction of the new pensions freedom reforms makes the scheme more attractive where the savings period is short because members can now liquidate their savings as a cash lump sum, which may encourage this cohort to take advantage of the tax relief and employer contributions on offer.

Pensions in the future

Looking ahead, it is fairly certain that many millions of these employees have no idea that the amounts they’re saving will not provide a decent income in retirement. There is a sense that as the government has recommended an amount to be saved, this amount should therefore do the trick.

Furthermore, the funding of the state pension is not sustainable, despite the introduction next April of a new flat rate state pension to replace the current system. Its structure, far from being “flat”, will actually be confusing for the general public and will result in disappointing pensions for those who have paid into the National Insurance system for less than 35 years or who have previously been contracted out of it in a workplace pension.

[embed_related]

The age at which state pension can be claimed is also rising. For women, this will rise to 65 by 2018, and for both sexes to 66 on October 6, 2020, and to 67 on April 6, 2028, with further substantial rises expected in the years after.

Many people in the industry believe the state can no longer afford to pay a universal pension. A survey of 200 financial advisers by life company Aegon revealed that just 4 per cent believed the new state pension system will still be in place in 30 years and around 39 per cent think means testing will be reintroduced. Ultimately, there may come a time when people, who have saved in auto-enrolled workplace schemes, wonder whether all they have achieved is to lift themselves off means-tested benefits.

The other big flaw in the system is that there is little support for the nation’s 4.47 million self-employed. Excluded from the auto-enrolment regime, their only route is to buy an individual personal pension plan, which will carry higher charges. The government has asked the Tax Incentivised Savings Association, a trade association working with the financial services industry, political parties and the Treasury, to come up with a solution. It favours the creation of a self-employed scheme with a higher government matching payment to compensate for the loss of the employer contribution.

SMALL EMPLOYERS FACE BIG CHALLENGE

The staging dates for employers with fewer than 30 employees started in June and continue through to April 2017. The Pensions Regulator initially predicted that 1.3 million small and micro-employers would be involved, but the number has risen to 1.8 million as business start-ups have increased and fewer firms have closed. With larger companies representing just 3 per cent of UK firms, the most challenging phase of the pensions on-boarding is clearly yet to come.

Two-thirds of smaller firms employ between one and four workers. The vast majority will not have a human resources department, and their managers will lack the time and expertise to oversee the auto-enrolment process, as well as the ongoing compliance requirements.

Two-thirds of smaller firms employ between one and four workers. The vast majority will not have a human resources department, and their managers will lack the time and expertise to oversee the auto-enrolment process, as well as the ongoing compliance requirements.

Many smaller employers may be trying to find a pension provider for the first time and the choice will be difficult. They have to choose from around 50 providers in a low-margin market that can possibly only sustain five or six, so a poor decision could create a headache later on in finding another provider prepared to pick up the pieces.

For their part, providers can afford to be picky about employers they take on to their books. They will be looking for low staff turnover and well-paid employees, and firms that do not fit the profile may find it difficult to obtain terms.

Finding a pension provider

Employers that cannot find a provider on the open market can use the quasi-government organisation NEST. At one stage, the Pensions Regulator promised to publish a list of providers who would guarantee terms to small employers. But the idea was dropped when the regulator claimed it could not monitor the quality criteria for inclusion on the list.

“We hope there are enough providers,” says Mike Cherry, policy director at the Federation of Small Businesses. “A few providers are not engaging with this. The pensions industry has never provided for this end of the market.”

Mr Cherry also points out that auto-enrolment is proving a massive administrative burden for the medium-sized firms already experiencing it. One complication is the calculations use band earnings to determine the contributions deducted from employees’ salaries, which change each year and are separate from National Insurance bands.

For small firms, auto-enrolment will hit just as the new national living wage is introduced and as businesses come out of a fragile economic recovery. The living wage will have a greater impact on smaller employers than for example the early movers, which primarily consisted of large retailers who turn over 80 to 90 per cent of their staff every year, so few are pension members.

Even firms with no legal requirement to pay into a workplace pension because their staff do not meet the auto-enrolment criteria will have to register on a new government website or face fines of £400, plus £50 a day.

Saving struggles