For half a century the pension pendulum swung between two extremes, from workers picking up a company clock at 65 to them dashing away from the workplace at the earliest retirement opportunity.

Over the past two decades, it has swung back so far that the dream of early retirement may soon be a thing of the past.

A combination of increasing lifespans and less generous pension arrangements, in particular the demise of gold-plated final salary or defined benefit (DB) schemes, means more people are working longer, either from choice or because they simply cannot afford to retire.

If you are under 40 now, then your retirement age is likely to be 70, and the numbers retiring at 50 or 55 will be a tiny minority

According to an Office for National Statistics (ONS) report in May, a record 9.67 million over-50s were still in work, while the numbers taking early retirement had fallen from a peak of 1.6 million in 2011 to 1.2 million.

A rising state pension age and the scrapping of the compulsory default retirement age, has also reduced the numbers retiring under 65, prompting insurer Aviva to predict that by 2029 early retirement “would be relegated to the dustbin of history”.

A rising state pension age and the scrapping of the compulsory default retirement age, has also reduced the numbers retiring under 65, prompting insurer Aviva to predict that by 2029 early retirement “would be relegated to the dustbin of history”.

Aviva savings and retirement manager Alistair McQueen observes: “If you are under 40 now, then your retirement age is likely to be 70, so early retirement will be at 67 or 68 and the numbers retiring at 50 or 55 will be a tiny minority.”

ONS figures show that a 65-year-old man today can on average expect to live another 18 years and a woman 21 years, against 12 and 14 respectively in 1950, and by 2039 one in twelve of us will be aged over 80.

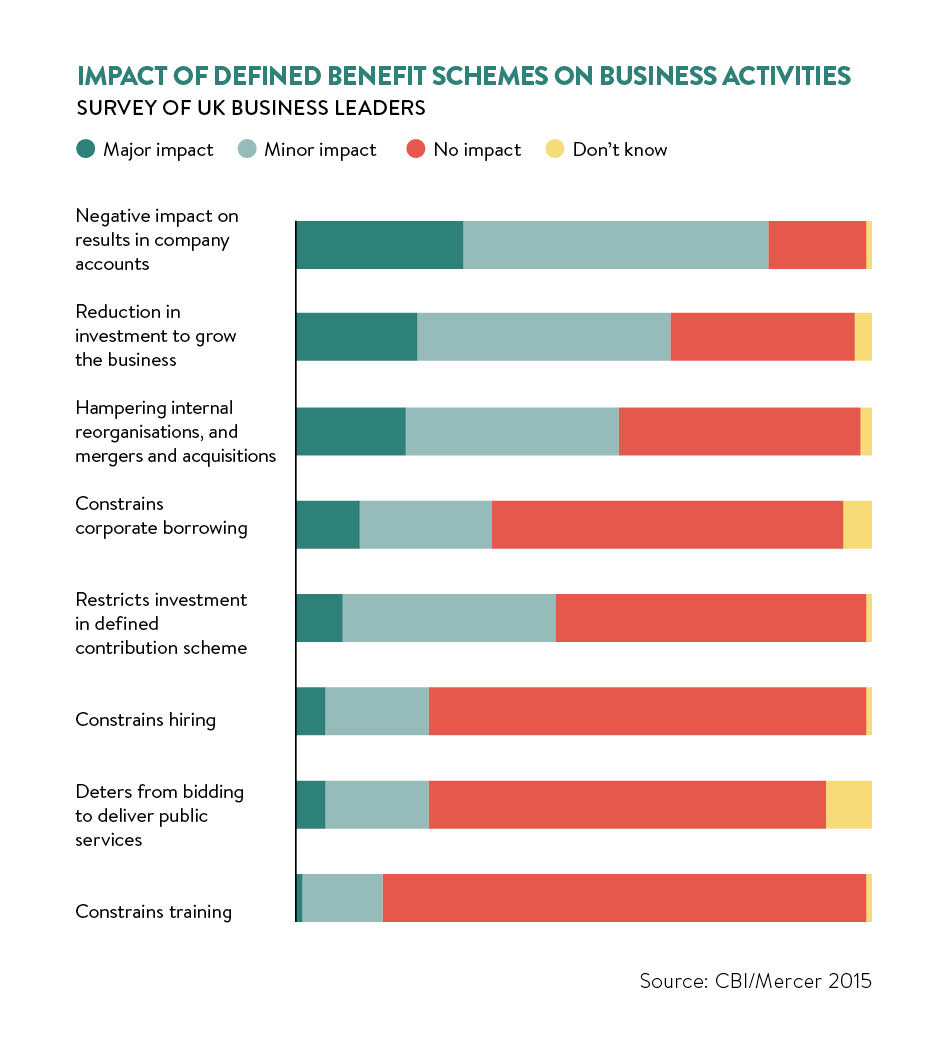

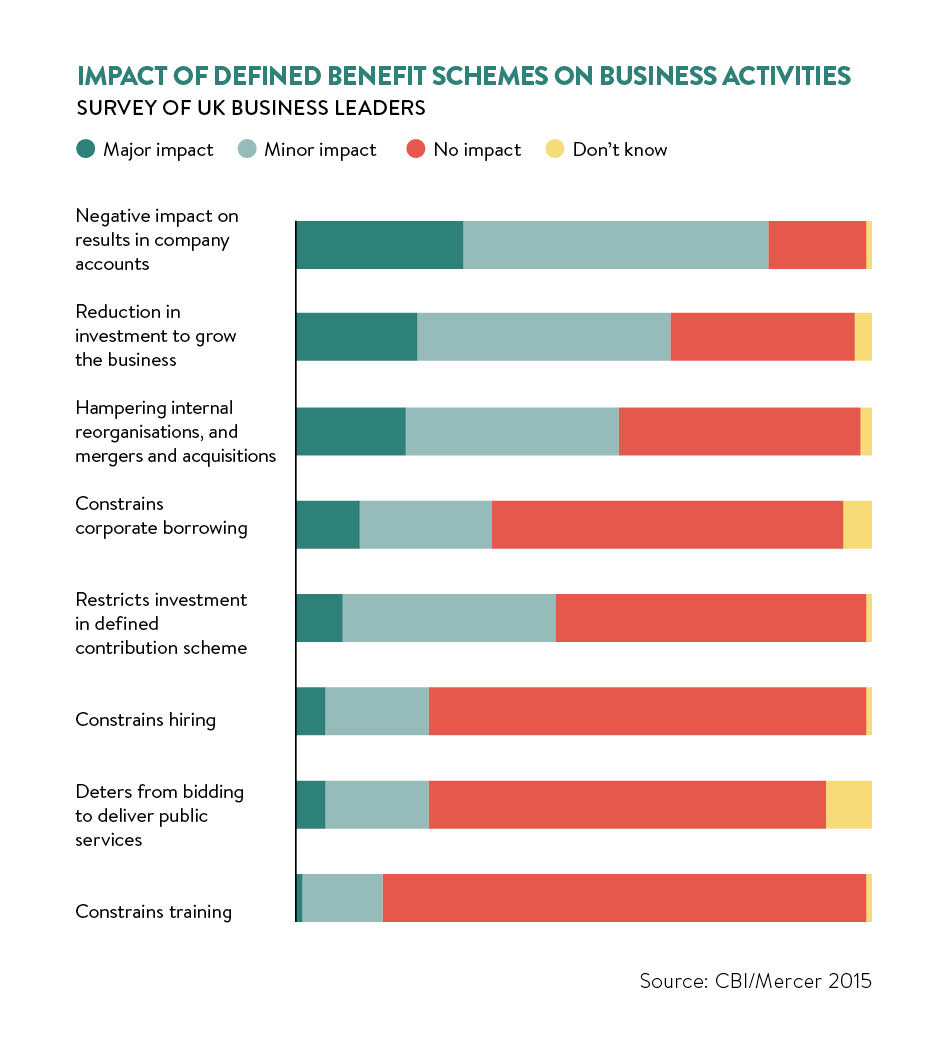

That increased longevity is an expensive millstone for companies with DB pensions, offering a guaranteed income based on salary and length of service, which provided the bedrock of retirement planning for millions of Britons in the last century.

While such schemes remain common in the public sector, where they are funded by taxpayers, in the private sector they are being phased out under the strain of life expectancy, economic turmoil, volatile investment markets and higher regulatory burdens.

According to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF), the lifeboat which has rescued 800 schemes since 2004, there are currently almost 6,000 private sector DB schemes of which nearly 5,000 are in deficit, a potential source of concern for the 11 million people – pensioners, deferred members and active members – depending on them to fund most or part of their retirement income.

Pension services provider JLT Employee Benefits calculates the combined deficit – the gap between assets and liabilities – of private sector-schemes was £341 billion in June, up from £241 billion a year earlier.

For FTSE 100 companies, the total deficit was £117 billion, up from £75 billion, reflecting the mammoth deficits at major employers such as BT, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and BAE Systems.

BT has the largest pension deficit of FTSE 100 companies, valued at £9.9 billion in June 2015

JLT director Charles Cowling says: “One of the problems is that a lot of the big deficits are with old economy businesses facing competition from new economy businesses without any of these legacy pension liabilities.”

It has been estimated that 1,000 schemes may eventually turn to the PPF, but Mr Cowling expects those backed by solid businesses to survive, adding: “Although it will be painful for a large number of companies, it will be manageable. Five out of six will manage it, but for a significant minority, if the writing is not on the wall, it soon will be.”

Many companies are so entwined with their pensions that the deficit casts a long shadow, highlighted by the collapse of BHS and the struggle to find a buyer for Tata Steel UK.

Funds and companies are bolstering assets and reducing liabilities by increasing contributions to record levels, protecting investment returns and scaling back members’ benefits.

Most firms have pulled up the drawbridge on DB schemes of which just 13 per cent are still open to new members, according to the PPF, while about ten million people are now in less-generous defined contribution (DC) or money purchase schemes, which build up an investment pot to provide a retirement income.

Mr McQueen says someone on £30,000 a year in a DC scheme would have to pay in 25 per cent of their income to reach the £20,000 pension they might have expected under the old system, but he points out that 10 per cent is generous under a DC scheme and half of that comes from the employee.

Employer contributions to the new schemes are often “paltry”, according to Alan Morahan, managing director of pension consultants Punter Southall Aspire. He says: “Income levels will be significantly reduced in relative terms to those currently enjoying their holidays, coffee shops and visits to the seaside because they became the accidental holders of very significant pension pots.

“That’s not to say it can’t be done, but we’ve got to get closer to the funding levels of the past. We’ve got to get society to understand that if you don’t put much in, you won’t get much out.”

As well as reducing future liabilities, funds must sustain investment returns for decades to come; not an easy task in a global economy reeling from the financial crisis, with volatile share prices and low bond yields as central banks try to extinguish the firestorm through historic low interest rates and quantitative easing. The Brexit vote has only added to market uncertainty.

Some companies have tackled the problem in imaginative ways, such as Dairy Crest, which transferred millions of pounds worth of mature cheese into its pension fund, and Diageo doing something similar with maturing malt whisky.

One solution is for companies to divert cash from the business and shareholders into their pension fund, but Darren Redmayne, head of advisory firm Lincoln Pensions, warns: “You have got to be careful not to kill the goose that lays the golden egg.”

Graham Vidler, director of external communications at the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA,) concludes: “Is early retirement doomed? Yes, for all but the wealthy few.”

This year the PLSA launched its DB Taskforce to examine problems facing the sector and, ahead of its findings, Mr Vidler says answers are needed to key questions such as, “Would we be better served by a smaller number of higher quality schemes and has the build-up of legislation over the years, which was well intentioned, had unintended consequences?”