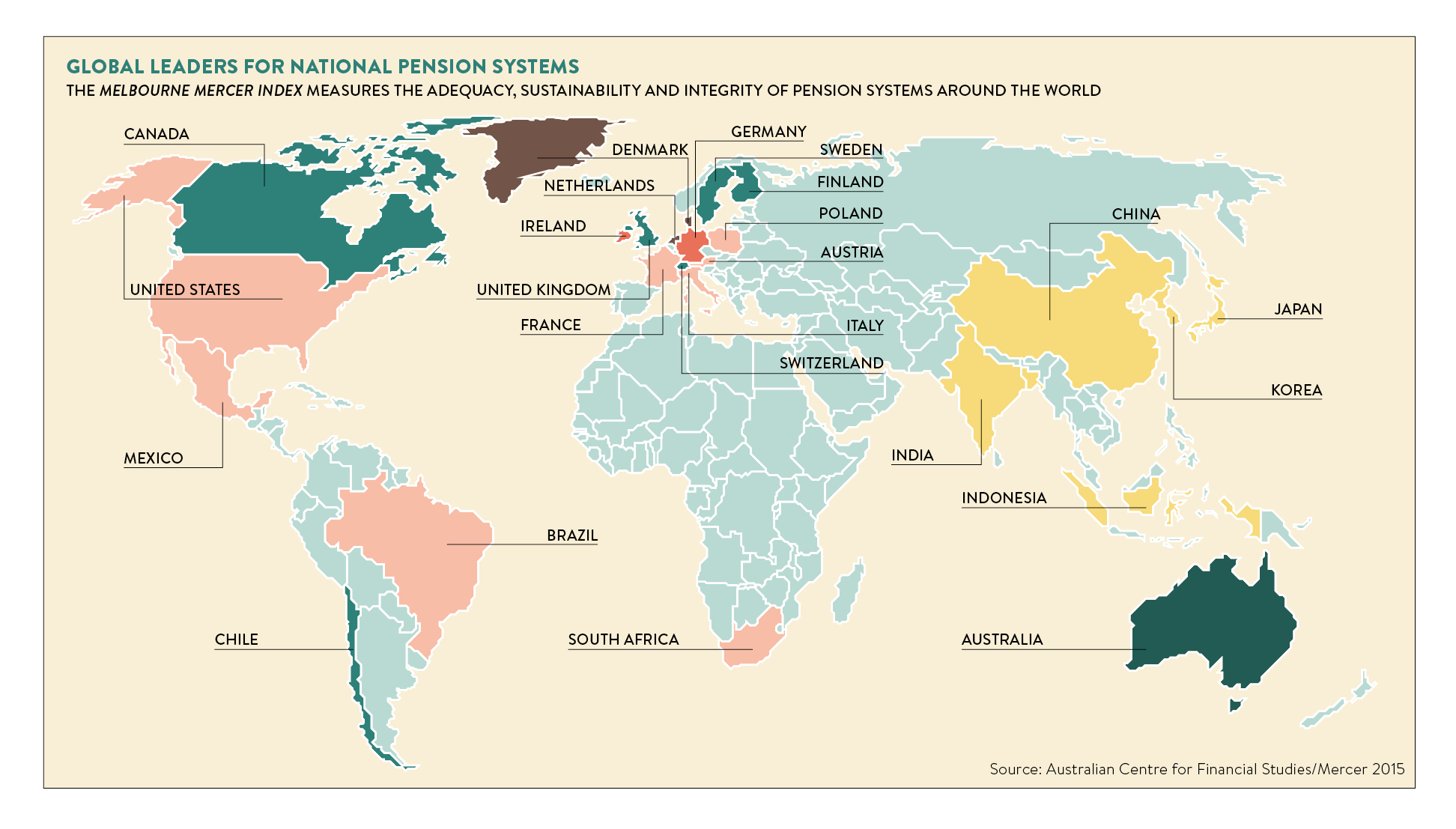

Denmark has been rated as having the best pension system in the world for the last four years running. The annually updated Melbourne Mercer Index, which compares and contrasts the merits of systems in large and developed countries, commends the Danish system for its general best practice, much of which flows from the scale of its pension schemes.

With only 25 active pension schemes for a workforce of 2.9 million, that equates to one scheme for every 116,000 people. This means fixed costs are spread over a bigger revenue base, giving the potential for bigger profits, a cheaper fee and a better service.

The contrast with the UK pension system could not be greater. For a workforce of 31.4 million, there are 35,710 defined contribution (DC) schemes and 5,835 defined benefit schemes giving a ratio of one scheme for every 756 people. Another way of cutting the data is to consider that there are 6.9 million members of DC schemes, which gives a ratio of one scheme for every 1,933 members. Whichever way you look at it, the figures are nowhere near as good as the Danish system.

Dr David Knox, an Australian-based actuary and a senior partner with Mercer, who authors the Melbourne Mercer Index each year, cites a ballpark figure of 100,000 members before a pension scheme can gain the economies of scale comparable to global best practice. Part of the reason is that a scheme with 10,000 members would be paying out some of the same fixed costs on IT, compliance and communication over a smaller revenue base.

He notes that in the UK some employers will subsidise member costs to overcome such scale deficiency, but by contrast in his home market of Australia most employers have now given up on such practices. Only the largest Australian employers, such as Qantas, Rio Tinto and Telstra, run their own schemes.

Unity and commodification

The trend among other countries ranked above the UK, which is in ninth position in the index, is away from single-employer schemes. A key influence has been government-mandated auto-enrolment of employees into pension schemes in Australia in 1993, Denmark in 1998 and New Zealand in 2007.

This has brought much greater uniformity and commoditisation. If there is a government-mandated level of employee contribution, then smaller employer schemes run on an enthusiastic amateur basis can appear a folly in the face of multi-employer schemes with lower costs and better capabilities.

The only certainty in the world of investing is if you can keep your administrative costs low then that is good for returns

One international scheme that relentlessly pursues economies of scale is ATP, into which all Danish employees contribute. In ATP’s 2015 annual report there is a chart showing how it has reduced administration costs every year since 2011. Currently, its members pay a fee equal to 0.23 per cent of their accumulated savings each year, made up of 4 basis points (bps) in administration costs and 19bps in investment costs. Equivalent fees in the UK typically sit around 0.5 per cent or 50bps.

As ATP’s chief executive Carsten Stendevad points out, ATP has one of the lowest charges for a pension scheme in the world.

“It’s a point of honour that we reduce costs constantly,” he says. “The only certainty in the world of investing is if you can keep your administrative costs low then that is good for returns.”

Part of the reason for the low costs is the not-for-profit’s schemes non-descript office 30 minutes by car to the north of Copenhagen. Another is a commitment to increasing digitisation that means most members will interact solely with an online interface rather than use post, e-mail or phone. Additionally, as ATP is mandatory and only offers a single investment choice, there is little complexity and no marketing costs.

Advocating scale

One of the biggest global advocates of scale in pension schemes is the internationally renowned pension expert Keith Ambachtsheer, an academic, author and consultant.

“The best-practice funds are mutuals, delivering packages of investment and benefit administration services to specific groups of stakeholders,” he says. In this vein, he describes the not-for-profit Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP), an organisation set up but run independently from the Ontario government and the Ontario Teachers’ Federation, as “probably the globe’s best-managed and most-famous pension delivery organisation”.

With $171 billion in assets and 316,000 members, OTPP has a scale so great that 80 per cent of investments are run in-house, cutting out the profit margins of Wall Street fund managers. Indeed, 80 per cent of $171 billion makes it effectively one of the biggest fund managers in the world. With such advantages, its investments costs are 27bps on average per member.

It is not just its relative cheapness that is attractive though. One of the areas OTPP excels is its in-house private markets teams. These own and manage many international assets outright. In the UK, the scheme is a 100 per cent owner of Bristol Airport, the Camelot Group and a 48 per cent owner of Birmingham Airport.

Dr Ambachtsheer sees the ability of the world’s largest pension schemes to invest so efficiently in infrastructure and property as key to better outcomes for members, and others agree.

Mr Knox says: “If you have got a scheme of only a couple of hundred million pounds, it might not be worth getting into infrastructure and understanding it.” For smaller schemes buying publicly listed equities and bonds are the best options, but these have suffered in the current low-interest-rate environment. Investments such as infrastructure tend to ride out market slumps better and generate rental yields that are inflation protected.

In addition, Mr Knox points out that the world’s largest pension schemes get to enter an exclusive club of investors. “When a fund gets to a certain size, it is invited to participate in certain investment opportunities, such as an IPO [initial public offering], a property or piece of infrastructure, that are not open to smaller funds,” he says.

Leading UK pension bodies, such as the Pensions Regulator and the Pension and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA), are aware of the problems of a lack of scale in the system. The regulator has hinted it will take action on “sub-standard and sub-scale schemes”, while the PLSA is creating new initiatives to follow the part it played in creating a shared infrastructure investment platform to help smaller schemes in 2014.

However, while the system focuses on the hurdles of completing auto-enrolment in 2018, the general consensus is that the problem of scale in the UK system will not be fully addressed until then.