Television’s place at the heart of mass culture is no more. Streaming services provide higher revenues to entertainment companies than traditional broadcasting and media consumption is growing more atomised by the day. People formulate their own programming schedules, cherry-picking programmes from an array of providers and watching on a variety of screens.

Even when we’re together, we are often alone in our own entertainment bubbles; a third of people in the UK say members of their households sit together in the same room watching different programmes on different devices, according to Ofcom.

With so much competition, media companies are vying to command a limited and in-demand resource: consumers’ attention. “Unlike the captive audiences of the past, today’s consumers can choose not only what type of content they want, but also how and when to enjoy it,” says Kevin Westcott, vice chairman of media and entertainment at Deloitte.

Data is widely regarded as the key to unlock better user experiences

Data is widely regarded as the key to unlock better user experiences. Having given consumers the power to choose what they want to watch and when, streaming companies analyse how long they watch for, what devices they use, where they are watching, what they watch next and so on.

This growing volume of data and the inferences made from it create a picture of viewing behaviours, tastes and attitudes. Netflix, which says it has around 250 million active users worldwide, divides users into “taste groups” of which there are several thousand.

In a fragmented market, delivering high-quality content is not enough. Media companies need to win the recommendation game. Those chasing economies of scale and the benefits of network effects will use algorithms and machine-learning to perceive what consumers will want to watch or listen to next.

More than 80 per cent of the TV shows people watch on Netflix are discovered through the platform’s recommendation system. Spotify, the popular music streaming platform, broadens its listeners’ musical horizon at the same time as narrowing the near-limitless listening options available to them by sending a personalised weekly playlist of 30 new songs based on the individual’s listening history.

But entertainment media companies need to be more compliant with consumers’ privacy concerns. “There are many consumers that seek personal entertainment, but a lot of personalisation features are not being done in a transparent manner,” says Dirk Spacek, managing associate at law firm Walder Wyss.

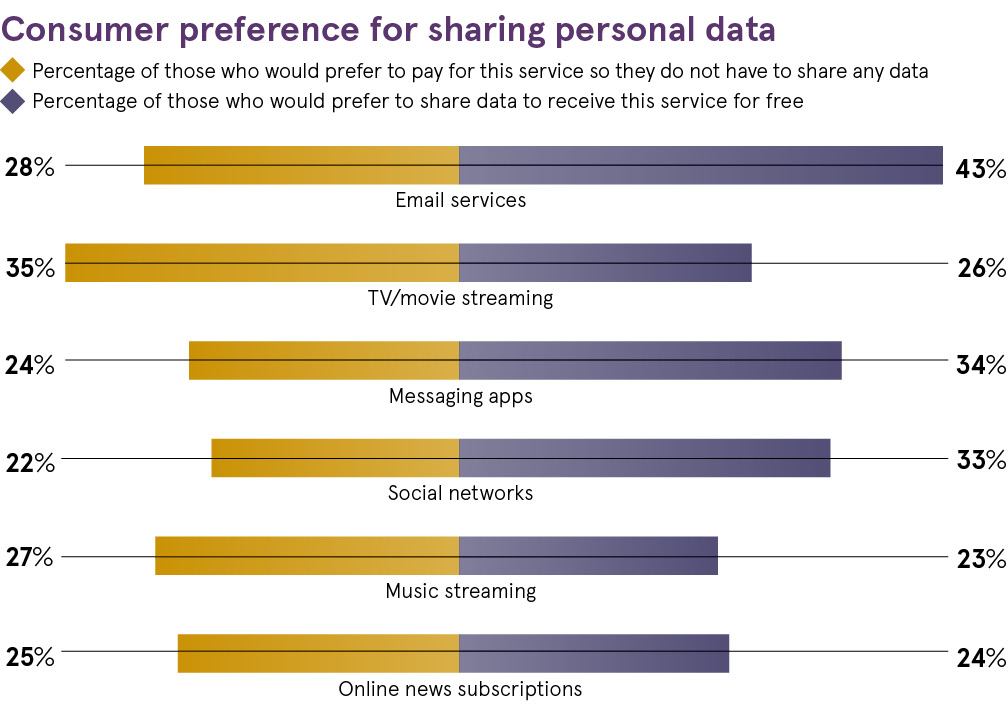

Indeed, Deloitte reports that 69 per cent of consumers believe companies aren’t doing enough to protect their data, and 73 per cent would be more comfortable sharing their data if they had some visibility and control.

Tristan Harris, a design ethicist and former product manager at Facebook, believes people should be concerned about how their data is used, sometimes to manipulate them. Techniques like autoplay which is used by Netflix, but not BBC iPlayer, for example, are designed to encourage immediate gratification and keep viewers hooked.

Reed Hastings, chief executive of Netflix, quips that his company’s biggest competitor is sleep. Alarmingly, he has a point. According to Ofcom, 32 per cent of adults and 31 per cent of teenagers have sacrificed sleep for streaming binges.

There are alternative streaming models that don’t rely on data collection, profiling or mass personalisation, but by their very nature their audiences are niche. One such, Mubi, is a film-streaming website that presents a rolling selection of 30 critically acclaimed films that are each available for 30 days, with one leaving and joining the countdown every day. Personal curation tops algorithmic personalisation, with the site’s selection chosen by film critics and tastemakers to complement new cinema releases and topical events.

In the European Union, the incoming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) could spell the end of profiling and algorithmic decision-making in the EU entertainment industry. “Under the GDPR, the customer has a right to object to automated decision-making that involves their data. This could affect profiling and personalisation entertainment features, such as the recommendation of similar content and notices about what other viewers saw or bought,” says Mr Spacek.

Across the Atlantic, the quest for dominance of data and eyeballs has sparked a trend for market consolidation. Among the FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Alphabet’s Google) the race is on to own the entire customer experience, says Mr. Westcott. Whichever companies can dominate content creation and delivery networks will possess an even more complete data picture from which to deliver hyper-targeted advertising and content. To this end, Facebook is licensing music and music video hosting, and Apple is branching out into Amazon territory with original TV programming.

Will this scramble for data enable a better user experience? One of the enormous successes of the Netflix model has been its focus on high-quality content without any ads. Netflix, which says it is spending $8 billion on content next year, is raising the bar throughout the industry and forcing its competitors to maintain a similar commitment to quality.

However, some fear consolidation, paired with the repeal of net neutrality in the United States, which critics fear will choke off smaller content providers, could compromise content standards and consumer choice long term.

Either way, if personal data is to be the bedrock of entertainment media, ethical protocols should be established for its use. Entertainment has the potential to become evermore enthralling and immersive as technologies such as augmented reality, artificial intelligence, robotic sensors, the internet of things, virtual reality, voice interfaces and 4DX cinema effects augmentation are commercialised. While television isn’t called the “idiot box” for nothing, it is by no means as ubiquitous or addictive as entertainment technologies to come.