It is said that Brits are among the world’s best queuers. An organised line of people is proof of our civility and a display of social order. On the whole, we’re proud of our ability to wait patiently behind others who arrived before us.

So it may come as a shock to learn that the queue – a cornerstone of our democracy – is under threat from technology’s relentless march.

In December, the first Amazon Go grocery store opened in the United States. The prototype shop lets customers select items and leave without filing through a checkout. An app on the customer’s phone logs what has been removed. Payment is automatic.

This trial, which received global headlines, is part of a concerted effort by retailers and financial technology companies to reduce the time it takes for people to buy stuff. Shopping can be an enjoyable experience, they reason, but waiting to settle the bill certainly isn’t.

In early grocery stores, customers would point out items they wanted for attendants to retrieve and bag. The process was slow and inefficient. Then came the familiar supermarket format in which people filled their own trolleys and paid at tills when they finished. It sped things up.

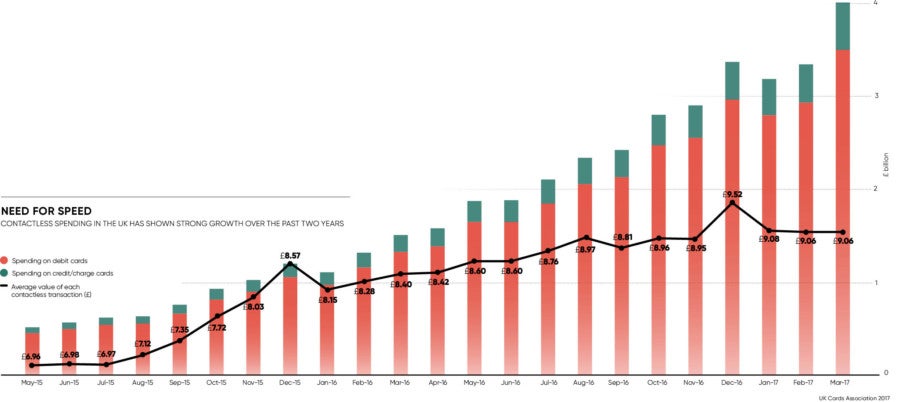

In the decades since, retailers have finessed the system with contactless payments, click and collect and self-service checkouts; all an attempt to reduce the pain of shopping for everyday staples, the stuff we need but don’t necessarily want.

Now supermarkets are moving towards a singularity in which efficiency is paramount. Barclaycard is trialling Grab+Go, a pocket checkout app allowing users to scan and pay for goods using a smartphone; again it’s a bid to make queueing obsolete.

According to Barclaycard’s Usman Sheikh: “The way in which people shop and pay has evolved significantly over the past decade, and as the use of mobile and wearable payments grows, we are constantly looking at how we can use technology to make our customers’ lives easier.”

Is this the future? Experts think so. In an era of instant gratification, when an increasing number of purchases are done online, supermarkets must mimic the ease of the dotcom experience.

“People want speed, simplicity and a personalised service,” says Moira Clark, professor of strategic marketing at Henley Business School. “The balance is reducing pain and enhancing pleasure. For millennials, the idea of shopping for boring things is an anathema, so there is a concentration of work in this area.”

Amazon Go looks like a decent remedy to the sickness, but challenges remain. For one thing, not everyone is comfortable with the model, particularly time-and-cash-rich retirees who were brought up in a world of human interactions.

A further issue is the practicality of the model, according to Professor Clark. Amazon Go might sit well in Canary Wharf, where adults pop in and out of shops buying only a handful of items. But what about massive out-of-town megastores with 50,000 stock keeping units?

A family shop is a turbulent experience, especially if the family is along for the ride. Children under the age of ten – the masters of chaos – are a formidable obstacle to Amazon’s Utopian system where shoppers act intelligibly. Could a six year old with busy fingers bring the whole thing crashing down?

These niggles aside, the get-in get-out format is a winner, says Oliver Wright, managing director for consumer goods and services strategy at Accenture.

The Amazon Go grocery store lets customers select items and leave without filing through a checkout

“The technology is clearly viable; it’s not pie-in-the-sky stuff. I think it looks like the future for a lot of convenience shopping because people want to make most transactions really quickly and the model is optimised for that,” he says.

“It will take some time for competitors to rival Amazon, given its huge R&D budget, but it will be widespread, especially if Amazon licenses the technology to other companies.”

The next decade will see rapid changes in the grocery market. A gap will appear between quick no-nonsense shopping and laid-back customer-centric experiences with lots of services bolted on. Supermarkets caught between these two poles will shrivel up.

“We will continue to see the growth of value retailers and direct-to-consumer brands offering quality and convenience,” says Helen Merriott, partner and head of markets for UK and Ireland Advisory at EY.

“The challenge for the supermarkets is how to get the balance right between chasing efficiency improvements to fund lower prices and last-mile delivery, while also funding higher levels of experience and service at touchpoints that matter. Retailers will increasingly need to offer ‘theatre’ and/or frictionless shopping experiences to be successful.”

Yet there is still room for smaller players who think outside the box. Speed, cost and convenience will all drive change, but so will quality, provenance and ethics. Evidence for this is Planet Organic, a London supermarket chain with seven shops.

It partnered with Unpackaged, a packaging solutions business, to install a self-service refill station at its north-London Muswell Hill store. Customers bring their own container, fill it with eligible products, such as cereals, coffee, wine, nuts and chocolate, then weigh it and pay for the total.

To some this sounds like a gimmick, but to others it fulfils a need to live well, not just fast or frugally. Successful players in future will continue to identify customer segments and create experiences that are optimised to their particular wants.

Amazon, which earlier this month bought natural and organic pioneer Whole Foods for £10.7 billion, has tapped into an important niche in the supermarket sector and its new shopping concept will appeal to the masses. But those who seek to kill the queue must remember that even in this hectic day and age, people have priorities beyond getting out the door.