The finance industry is developing new operating models, cutting the costs of their legacy businesses and offering services to compete with the innovative forms of financing offered by startups.

Gary Reader, KPMG’s global head of insurance, says: “For the last six years, we have observed a battle for the balance sheet and the future will be a battle for the customer. That is at the top of every single organisation’s agenda. Although firms have spoken for years about being customer-centric, to a large part, they have not delivered that model.”

New models of engaging with customers are erupting on to the street, from startup firms and big technology businesses. Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending services and insurance, low-cost online-only challenger banks and do-it-yourself portfolio management are all fighting for the ground occupied by established business models.

Tech giants like Google and Amazon or “smart-retailers” such as Starbucks are in a position to exploit their massive customer base, with their detailed data on customer behaviour, payments apps, customer loyalty and real-time communication.

This encroachment has taken root. Amazon began lending to US-registered Amazon sellers in 2013, to support inventory purchases for example, and has been expanding into new countries reaching the UK in December 2015. Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has successfully become a massive distribution platform for an investment fund in China. They have the capability.

The major advantage that tech firms and indeed smart-retailers have is their established distribution mechanisms and access to high-quality data, with a strong capacity to process that information. They could potentially distribute financial products with limited regulatory burden, and leave the manufacturing and utility banking, with its associated risk, to established, regulated players.

However, finance houses are fighting back by engaging with the opportunity that these models offer. Fintech startups are seeing unparalleled attention from the big finance houses. P2P lending now contains a considerable amount of bank and investment fund capital. Direct competitors to the status quo, such as DIY wealth manager Nutmeg, have seen investment from businesses they intend to disrupt such as Schroders Asset Management.

Banks are prevented from providing many services by regulators who want to see their retail deposit business separated from any investment activity that carries a large risk-reward dynamic. This enforced separation breaks cross-subsidisation of one business cash flow by another, for example, supporting trading with retail deposits.

“Once you get all your UK retail deposits in one spot and you can’t subsidise any derivatives trading or long-term lending, then we are going to find out what the consequences of the maturity mismatch are; then we are going to find out how profitable these banks really are and how important the cross-subsidy has been for banking,” says Bill Michael, global head of banking and capital markets at KPMG.

Different value chains are being disrupted, with areas like payments seeing interventions from multiple providers such as Apple Pay, World Pay and PayPal. While these all leverage existing bank-based electronic payment models, the system has become a value chain in its own right through the data about payments that is captured, rather than the infrastructure that delivers the payment.

The capital markets element of banking is also seeing disintermediation through the development of all-to-all trading venues that allow non-banks to trade with one another. Pre-trade data information exchanges are evolving, allowing the asset management clients of banks to work out which of their dealers would be best placed to offer them a decent trade. In this context, the winners in the banking community are those that can work with these third parties to offer improved services which include the new functionality on offer.

Banks are not alone in being under threat. Investment managers have been facing criticism by UK authorities over a period of years for being less than transparent about fees and their value. Funds that are actively managed by a portfolio manager, rather than passively carrying the assets that make up an index, are increasingly coming under fire, in some cases for mimicking the performance of an index and in others for underperforming many passive funds. The costs associated with actively managed funds are considerably higher than those of passive funds.

Tom Brown, global head of investment management at KPMG, says: “There is a huge amount of pressure on margins. Investors aren’t prepared to pay the sort of fees they had in the past. There is downward pressure on revenue and the cost of running these businesses is ever-increasing.”

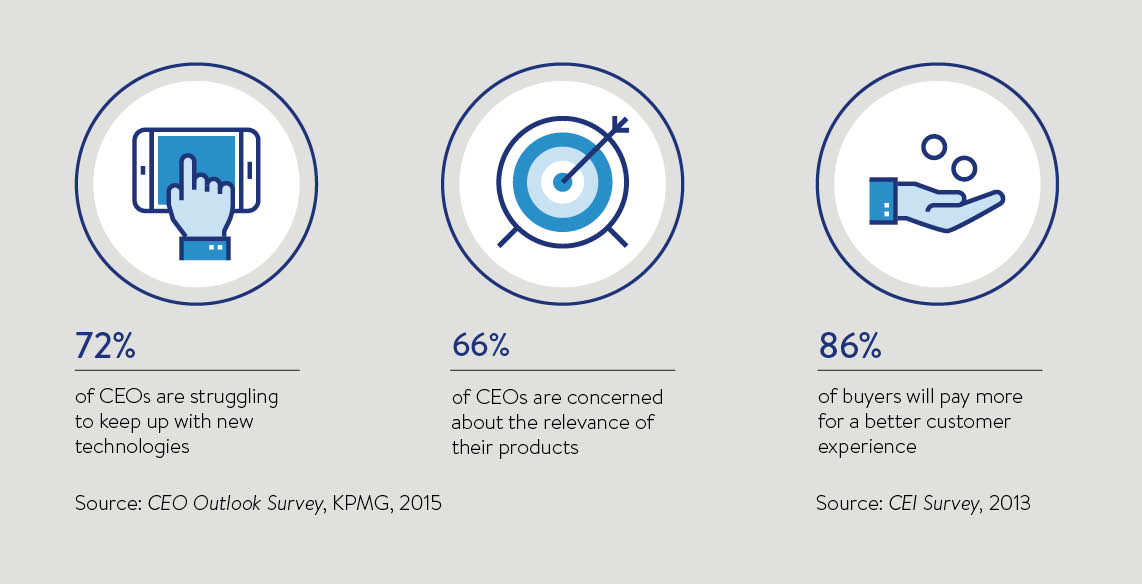

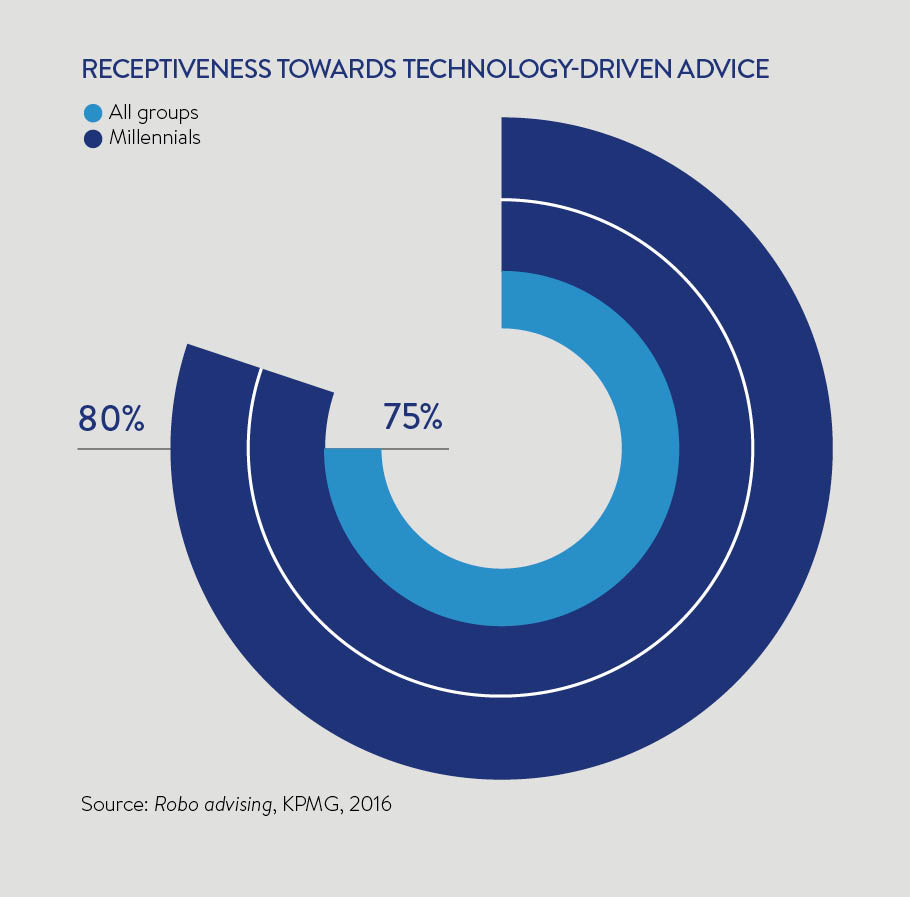

Consumers are facing an advice gap that will leave many unprepared in their savings and investment requirements and, combined with the gap in the performance of financial institutions and more technology-aware retail and tech institutions, alternatives to the traditional wealth managers are being sought.

“The wealth management industry is buzzing about robo-advisers. These are the automated, digital wealth management services taking the industry by storm. Already big and growing in the US, robo-advisers will become mainstream around the world in the next few years,” says Mr Brown.

The public is hungry for better service and, under new rules, it is easier than ever for retail customers to switch service providers

Startups that offer individuals the opportunity to back test-trading strategies and then run live money on them are effectively giving consumers the potential to operate as hedge funds, including following other peoples’ investment strategies. Investors in the real estate market can access various online digital real estate business models such as BrickVest. The extent to which these DIY-type business models will really challenge the existing players remains to be seen. “This is all about cutting out the middle man,” notes Mr Brown.

The insurance business is facing disruption from the increased capacity to gather and analyse data in real time. The model of providing a lump of capital to reimburse loss, calculated against historical probability, is changing.

“The trend is very much moving from protection to prevention,” says Mr Reader. “How can we stop people being flooded? How can we use wearables to help clients manage their health? How can we better use telematics to reduce accidents among young drivers and reduce premiums too?”

The public is hungry for better service and, under new rules, it is easier than ever for retail customers to switch service providers. As brands such as Apple and Amazon make themselves more conspicuous in the process of making payments and borrowing money, the brand strength of traditional banks, asset managers and insurers is under threat.

“There is recognition within organisations that they need to do something; they need to innovate and often they create a department off to the side,” says Mr Reader. “The challenge is a creative solution won’t work well if it is set the same sort of performance metrics and requirements that the rest of the organisation runs on – it gets stifled. Innovative solutions require experimentation and failure to get right – the startup mentality of fail quickly and move on.”

This opportunity is visible to many financial technology startups and, while several are supported by major finance firms, others position themselves as the antithesis of traditional financial services. Their key strength is the ability to try, fail and try again when building their businesses, at rapid pace and free of the rules that determine how banks operate. Yet they lack an established customer base and capital.

Mr Michael warns that new models will face a challenge at the point where a business model loses investors’ money. “Don’t forget that the fundamental purpose of financial institutions is to disintermediate and risk manage,” he says. “Things like peer-to-peer lending and insurance can easily come unstuck because, when people lose their money, there is an outcry.”

The big inhibitor to any new entrant is the regulation which places considerable burdens upon traditional firms, demanding transparency, capital reserves and protection against various risks.

“I am personally sceptical as to whether these big players want to take on the regulatory risk from going into financial services,” says Mr Brown. “I wonder whether a more obvious angle would be closer joint ventures and alliances between financial services and these big tech firms. The example of Alibaba is often cited, but there are not many others of scale, which makes me think it’s not an obvious thing for big tech companies to go into, certainly not in a very rapid way.”

In many other businesses, manufacturing is separated from distribution, the former tending towards commoditisation. Firms from Nestlé to Nike to Apple focus on brand, quality control and design, with third-party factories building the products. Offering a commoditised service as a utility would drive down margins and lower the barrier to entry for challenger firms.

KPMG’s Mr Michael concludes: “We are helping clients move from a vertical world to a horizontal world, where you use alliances, joint ventures and third parties. A UK bank, subject to the ring-fencing of its wholesale business, which has a customer that exports to Brazil, will find it can’t put that business within its ring-fenced bank and will use a bank in Brazil, but the customer won’t see that.

“In the past, banks tried to do most things themselves. The economics of the business model have now fundamentally changed – all the weapons now have to be used to redefine how a financial services business delivers service. Alliances, fintech, shared utility companies, new pricing models – they’re all necessary in what is becoming for some an existential battle.”

Q&A WITH KPMG’s BILL MICHAEL

Transforming capital markets and banking

Bill Michael, Global head of banking and capital markets KPMG

Q: What are the regulatory pressures shaping banks’ operating models?

A: Financial services firms are morphing. Regulations like the ring-fencing proposals in the UK and intermediate holding company requirements in the US are separating the retail and capital markets parts of the business, and consequently we will see the performance of each side more clearly. A fundamental review of location strategies and businesses is well underway, with the synergies of size and complexity now seriously challenged.

Q: Is banks’ existing technology an inhibitor to effective service provision?

A: Yes, the effect of legacy technology is threefold. Firstly, banks are not investing enough in developing growth strategies as they spend most of their budget on regulation, running the bank and risk mitigation.

Secondly, they are unable to get a single picture of customers and business profitability very easily, and data models have not kept pace with the social media revolution.

Thirdly, their ability to re-engineer their legacy infrastructure is challenged because of its complexity, making the cost of service improvements higher than it ought to be.

Q: Do technology firms have a massive advantage in customer engagement over banks in that new world?

A: Yes, because their digital design is based on customer engagement and consumption, rather than financial services product processing. Banks have developed systems that work from the product towards the client, for example taking deposits. Big tech firms, “smart-retail” firms, and even fintech startups, are closer to the customer through their use of online and mobile contact.

The other advantage consumer companies have is the better quality of data through the customer life cycle; for example, Ocado know what you had in your basket in your previous shopping, what you typically need in a week and how much you spend.

Q: What impact does that have on the industry?

A: In terms of consumer banking, it’s an opportunity for companies such as Starbucks or Amazon to disintermediate the banks. Their customer relationships are well established as distribution models. This suggests banking product manufacturers could become utilities in the future.

For corporate and commercial banks, the challenge is more likely to originate from companies such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) technology specialists, database giants and SME community accounting technology provider Sage, for instance. These technology specialists are the providers of choice for corporate treasuries and chief financial officers, and see a wider universe of financial data than banks.

In capital markets, where regulation and the cost of capital have had the most profound effect, we see a rapid disruption of traditional markets businesses and the emergence of tech-driven new-entrant companies, such as Citadel Execution Services, a broker that has grown from a hedge fund company, and agile electronic brokers such as Saxo Bank.

In all instances, we see the development of partnerships, possibly of a retail bank and large consumer-facing firm such as Starbucks, or a commercial bank and ERP provider.