You believe we are entering a new era of consumerism which you call ‘The Kindness Economy’. What does this mean to you?

It’s a new economy that businesses have to get used to, one that’s built on a new value system. If you look at the past 30 years, consumerism has been peaking and the whole infrastructure of retailers has been around who is the biggest, the fastest, the cheapest. It’s all been down to operations rather than an understanding of how people are living.

Big retailers will give you many reasons why the high street is failing and this won’t be among them. The first reason they give is the internet, the second is the economic climate, that most people are strapped for cash, and the third has been the uncertainty of Brexit.

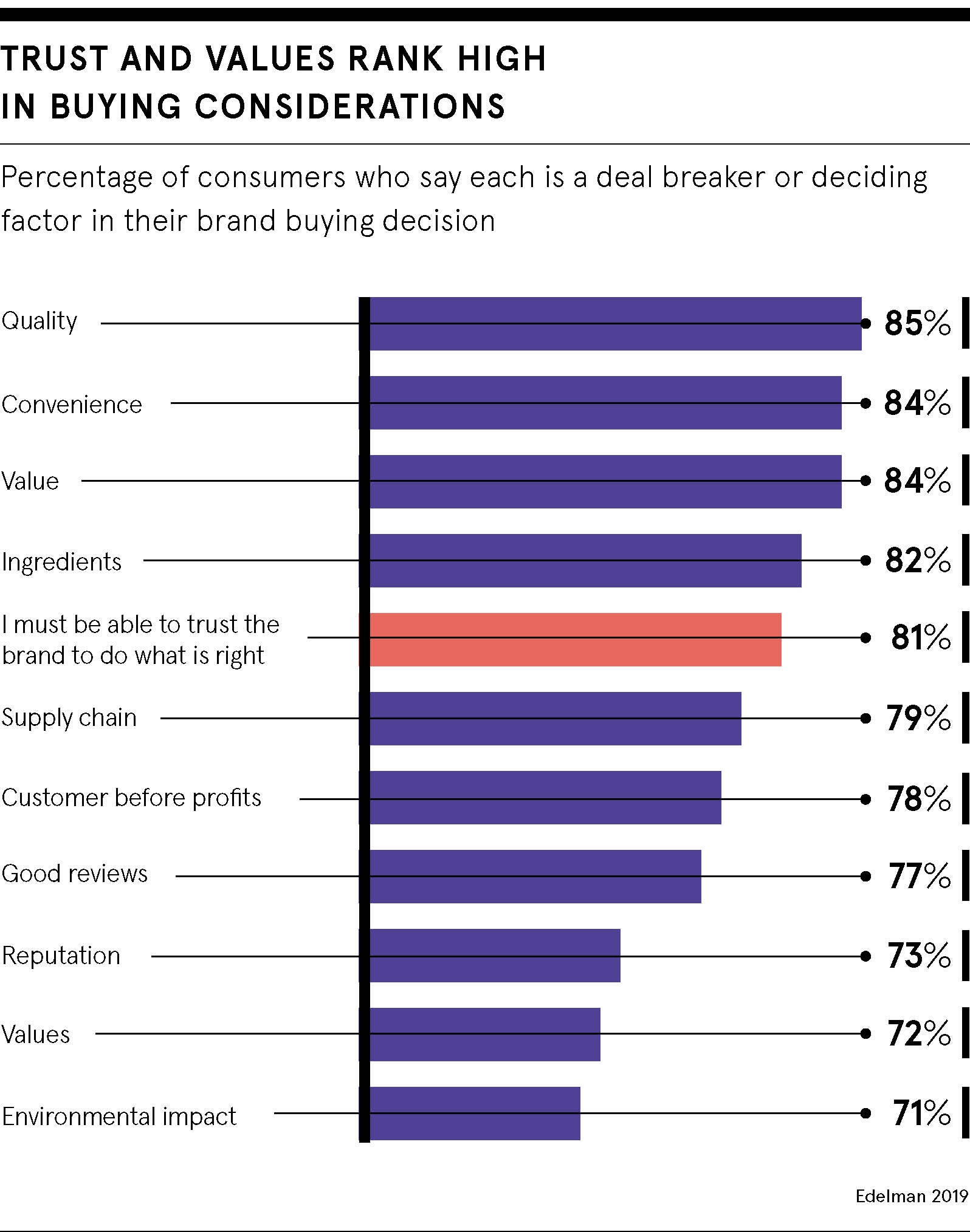

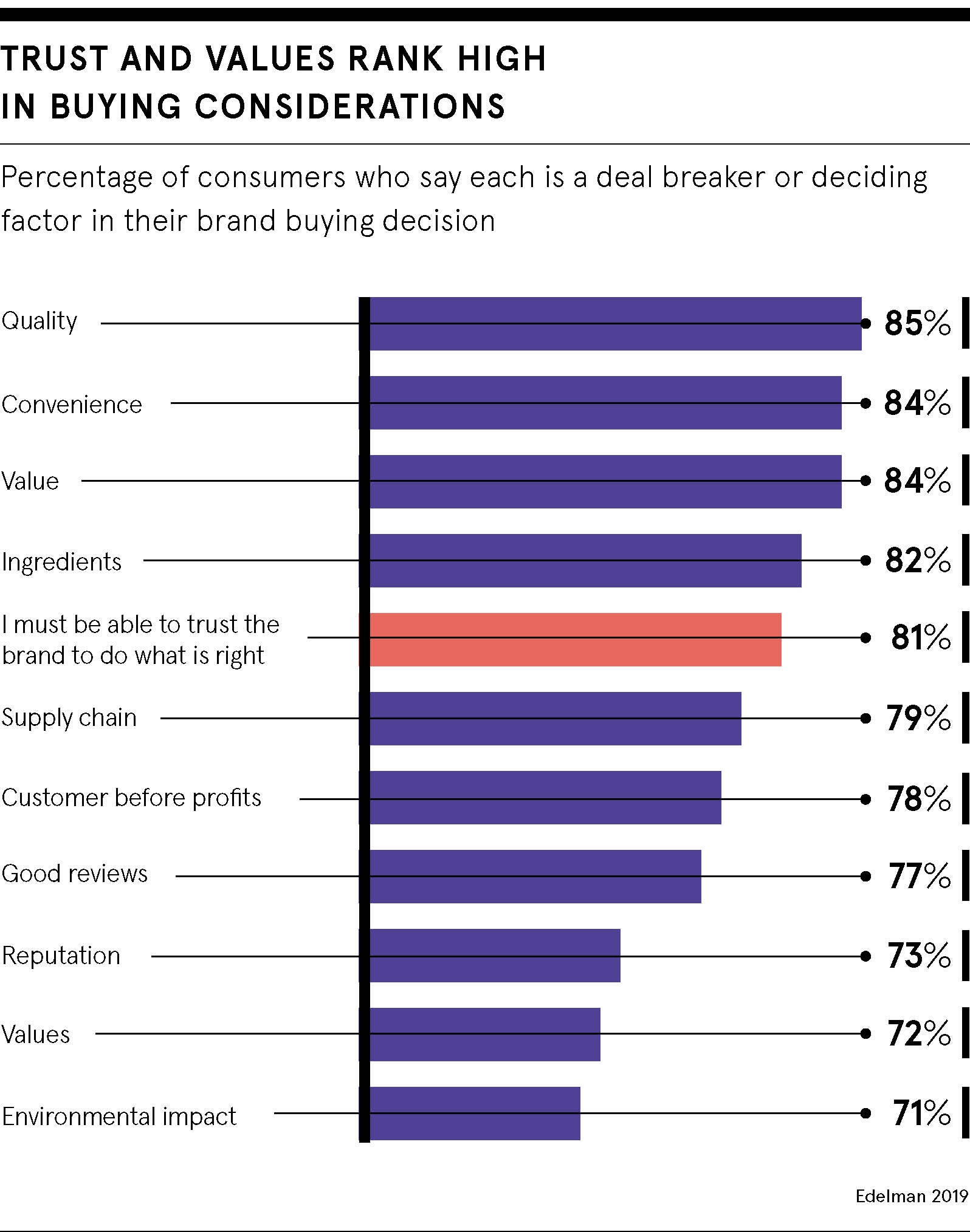

Of course, all of these play a part, but the biggest reason has been that we’ve changed our value system as people. What we’ve come to realise as a society is that the tenets of capitalism, that ‘more equals better’, is not going to be better for us as people or for our planet.

The tenets of capitalism, that ‘more equals better’, is not going to be better for us or for our planet

The indicators are everywhere. We now have a real backlash against fast fashion. We’re seeing a rise in recycling, upcycling, vintage, secondhand. We’ve got global marches, we’ve got a real mistrust in large organisations. And on the back of that a rise in volunteering.

Old-school consumer culture, reducing people to what they buy rather than who they are, is dying. And businesses that were set up to feed that beast are crumbling. This new era, The Kindness Economy, is going to be about sentience. It’s going to be about care, respect and understanding the implications of what we are doing.

The businesses that can connect with people as people, not merely consumers, will start generating a whole new way of shopping.

Do you believe The Kindness Economy, as a new way of creating business, is the secret to reinvigorating the UK high street?

Absolutely. It makes for a better world. And as a result we will lose the boring, boring high street we had in the 1990s and noughties.

A great example is Eat 17: a couple of lads from Walthamstow [north-east London] saw the local Spar and thought, “We can do something with this.” They realised there was not much money in the area, so they kept the low-priced stuff, but they also started to work with small, independent producers. They get their sausages from the local butcher and they get the local florist to deliver. And they’ve created this brilliant supermarket. There’s a space where people can sit and eat too, instead of a dodgy cafe, they get the greatest street food vendors to come.

Now areas like Walthamstow will pick up and you’ll suddenly notice that a chain shop has come in because Eat 17 has created the footfall. They’ve created the place to go.

These are the new anchors of the high street. Instead of “Oh, we have to get a Marks & Spencer or a Debenhams in here”, the new anchors won’t even be all retail, they could be a yoga studio, a crèche, community spaces with a socialising function. So yes, we’re going to have less retail, but we’re going to have better retail and better places to connect.

What is the triple bottom line and why is it important?

The triple bottom line is people, planet, profit, in that order. Put your people first, because the planet will continue without us, but if we want to be on it, we need to change. We need to understand how we’re eating, how we’re travelling and how we’re buying. Put people first and it will be us that can make that change happen. And this means both people in your business and people outside your business. Not consumers or staff: people.

In your book Work Like a Woman, you talk about dismantling alpha culture and embracing more traditionally female qualities. Will this redress the imbalance of having so few women on retail boards, despite retail staff being predominantly female?

It is shockingly bad; 70 to 80 per cent of purchasing decisions are made by women. And in the retail business, there are huge numbers of women in the roles of buying and behind the scenes in human resources, but when it comes to the board? All you see is men.

In the past, alpha culture was prime, because we’re talking about numbers, we’re talking fast turnover and we’re talking about old codes, statistics, data. And the belief was that this kind of work didn’t need the “soft stuff”, the understanding of what women are buying, what they want. So that element of retail was kept out of the boardroom, but thankfully this is shifting.

We’ve had three trajectories over the 30 years I’ve been in the business. In the 1980s, it was an era of Status Symbols: “I shop, therefore I am.” Then we moved on from that because it was rather gauche and obvious, and moved on to Status Stories. These were all about “discovering” things from small, unknown designers, very rare and special. The food scene really took off at this time.

Now we’re moving into what I call Status Sentience. A shift from buying from, to buying into. You buy into brands that connect with your values. This requires very different ways of creating business; it requires instinct and sensitivity. It’s built on the so-called soft stuff that previously had no place in business, in the boardroom. And that has to come in now.

You are credited as the person who turned Harvey Nichols into a leading brand. What are the lessons from your time there that are applicable to retailers now?

When I joined Harvey Nichols, it was loss making. There was a team of five of us on the board and we were given 18 months to make it profitable, with very little budget. And so we worked instinctively. That’s a very important word, “instinctively”. As creative director, I instinctively connected the business with what was happening culturally.

We couldn’t get the big designer brands, like Harrods could, because we weren’t a “sexy” business at that time. So I went after young designers and gave them free space on the shop floor. I used to go to the Royal College and Saint Martin’s, meet with the lecturers and say, “Tell me who your best students are and I’ll get them work”, next thing we had a young Thomas Heatherwick designing the window.

Then I heard about Jennifer [Saunders] writing Ab Fab and offered the cast access to the store at anytime and to let them borrow clothes. When the show came out they only mentioned shopping at Harvey Nicks. And people started to feel cool shopping there.

We opened up a bar and a restaurant, which was the first time anyone had done that in a department store. It redefined the shopping experience and the by-product was that we sold stuff. And then it got bigger and more successful, and in came the finance people and we lost what was really special.

But now we’re going back to that. All those operations set up simply to shift stock don’t know how to harness that magic. That’s why House of Fraser has collapsed. That’s why we’re seeing problems at Marks & Spencer. You have to be nimble, you have to be instinctive. You have to understand people’s pains and get excited by them and take risks.

One year we emptied the windows, put nothing in them and gave all the money to charity. That was a risk, but it was instinctive, knowing the climate, knowing the feeling. And that is what the future of great retail is going to be.

That’s why we’re seeing brilliant brands grow, the Glossiers, the Caspers, they are understanding our needs, they’re connecting with what people want. And these are the brands that will really do well in the long term.