Commercial enterprises have a vested interest to protect the value of veracity and maintain consensus around truth. Yet, far from abating, most people in mature economies will consume more fake news than truth through to 2022, according to research by technology consultancy Gartner.

The rise of truth as a binding force in scientific, legal, political and commercial practice was a gradual and hard-won achievement, argues the journalist Matthew d’Ancona in his book Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back. “Those who blithely assume that its threatened collapse in the political world will have no ramifications in the rest of civic society are in for a shock,” Mr d’Ancona warns.

Information plays such a huge part in the effective functioning of markets that they are particularly vulnerable to the manipulation of truth for commercial gain. Gartner predicts that within the next two years a major financial fraud will be caused by the spreading of highly believable falsehoods through financial markets.

“Trading on the stock market relies heavily on the automatic and high-speed consumption of content, parsing of sentiment in news stories, and application of algorithms,” explains Magnus Revang, co-author of the Gartner report.

As companies increasingly demonstrate their civic values, they are vulnerable to politically motivated attacks. In August, Starbucks was the subject of a high-profile hoax dubbed Dreamer Day. Originating from the recesses of the far-right bulletin board 4chan, the hoax was intended to troll Starbucks’ chief executive, the left-leaning Howard Schultz.

A fake campaign spread through social media saying that Starbucks would offer a free or heavily discounted iced coffee to all undocumented immigrants in the US on August 11, 2017. All they had to do was line up at branches of Starbucks, where the pranksters hoped they would be met by US immigration officers.

In volatile and unstable markets fake news has the greatest potential to wreak havoc. In June, a fabricated news story, also traceable to users of 4chan, claimed that Vitalik Buterin, co-creator of cryptocurrency ethereum, had been killed in a car crash. Mr Buterin eventually posted a selfie of himself to disprove the rumours, but by that point 20 per cent of ethereum’s $4-billion market value had been wiped out.

Fake news is a thriving industry dancing on the edges of the so-called dark arts

There is more potential than ever for companies to become implicated in the fake news cycle, both as its victim and as its colluder. Indeed, fake news is a thriving industry dancing on the edges of the so-called dark arts.

With relative ease, and without having to visit the dark web, a company can employ a marketing agency to set up anonymous chatbots that will chirp endorsements of their brand through fake accounts on Twitter and YouTube. These services can cost as little as $7.

Similarly, a recent investigation by online magazine The Outline has found companies secretly paying journalists to write favourable articles about their brands on mainstream news websites such as Forbes, Fast Company and HuffPost, without the platforms’ knowledge and without declaring the content as sponsored.

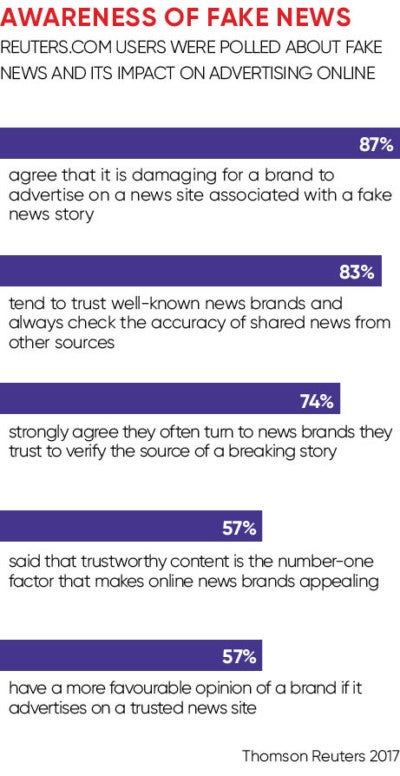

Companies that advertise on discredited news sites not only fund the devaluation of legitimate news outlets, but they also undermine their own brands. According to a poll by Thomson Reuters, 87 per cent of consumers agree it is damaging for a brand to advertise on a news site associated with a fake news story, while 57 per cent, rising to 60 per cent at director level, say advertising on a trusted news site confers a more favourable impression.

Mr Revang is pessimistic about the potential for artificial intelligence (AI) to eradicate the fake news problem. The more we employ increasingly sophisticated algorithms to identify fake news, the more this will inadvertently lead to the creation of evermore sophisticated forms of fake news. He says: “We are also not only training the AI to detect fake news, but also training people to create more believable fake news.”

Most fake news is made by individuals, with AI functioning as a content distributor, not as a creator. This won’t last long. According to Gartner, as early as 2020, AI will be able to generate sophisticated fake news that will outpace the ability of AI to detect it, driving an arms race in the weaponisation of information.

Gartner predicts that the AI-driven creation of a “counterfeit reality” will foment further digital distrust. This will include not only words and pictures, but also video. In July, computer scientists at the University of Washington, using a form of AI called adversarial generative networks, proved they were able to manipulate and create video footage, and perfectly match it to any audio recording.

As fake news grows more pervasive and sophisticated, companies might be tempted to test the limits of truth. Indeed, simple economics dictate that it is a lot easier to make things up than it is undertake reliable research, and it is a lot cheaper to produce fake news stories than it is to detect and repudiate them.

But short-term gains will only be followed by long-term reputational costs. Instead, Gartner says, companies have a pressing responsibility to draw up a suitable code of digital ethics for their industry that should inform their public relations, marketing, product development and sales practices. At the same time, it would be in companies’ best interests to train employees to ensure they are inclined and skilled to discern the truth.

Commercial enterprise should also collaborate to quash the economic incentives that underpin the fake news market. Towards this end, social media sites and technology platforms such as Google, where fake news flourishes, could do more to pull their weight.

The information company LexisNexis relies on data from multiple news sources to provide its business-to-business customers with reliable data for legal, regulatory, research and reputation management purposes.

Pim Stouten, director of strategy at LexisNexis Business Insight Solutions, explains that social media remains an opaque category. “Most social platforms know their data is quite the gold mine, so they are reluctant to give you access to the full dataset. You have to rely on them that you are getting a complete subset relevant to the research or analysis you are doing,” he says.